March 2, 2012

There continues to be a perception that credit is difficult to attain for both consumers and businesses. Broadly speaking that is not the case. In a letter to the editor in today’s Wall Street Journal about financial regulation, Treasury Secretary Geithner said that “Credit is relatively inexpensive and growing across most of the U.S. financial system, although it is still tight for some borrowers.” He is right.

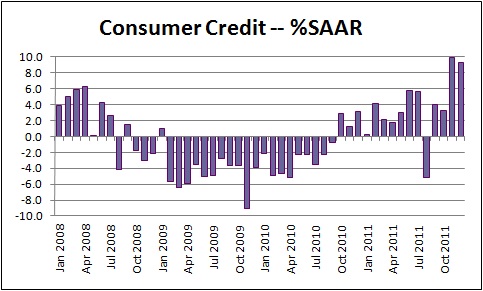

The Fed publishes a series on consumer credit which covers all types of consumer borrowing except mortgages. When the economy collapsed following the demise of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, consumers had far more debt than they could comfortably repay. As a result, they paid down debt every single month for two years. By October 2010 they got to a point where they were once again comfortable with their level of debt. Their willingness to take on new debt started off slowly but has been gradually gathering momentum. Indeed, the increases in November and December 2011 were the largest back-to-back increases in consumer credit in more than a decade.

What types of loans are these? And who is making them? The Fed splits consumer credit into two broad categories – revolving and non-revolving credit. Revolving credit is, essentially, credit card debt. Of the gains late last year, 20% represented an increase in relatively expensive credit card debt. Of that amount the bulk was provided via the credit card programs offered by banks with additional help from finance companies.

The remainder of the late-2011 run-up in consumer credit, or 80%, was non-revolving debt which includes auto, boat, personal, and student loans. While banks have played a role in extending this type of credit to consumers, almost two-thirds of the November /December increase was student loans made by Sallie Mae. Clearly, consumers do not appear to be having too much difficulty attaining credit.

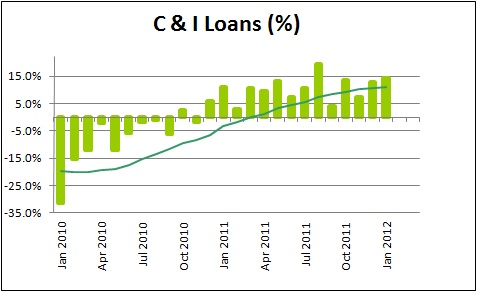

On the business side, commercial and industrial loans made by banks have been rising steadily for more than a year. During that period of time business loans have risen 11.1%, more than double the growth rate of nominal GDP. For those firms with good credit ratings, banks seem more than willing to make loans.

As the economy gathers momentum, more jobs are created, and the unemployment rate continues to decline, credit should become easily attainable by an even broader group of borrowers. This brings up a potential problem.

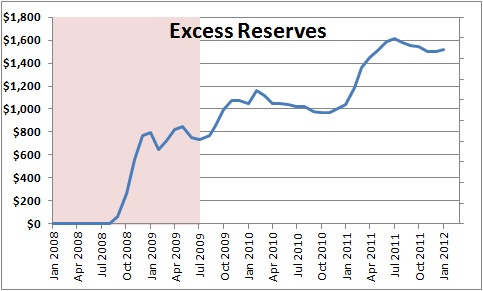

During the past couple of years the Fed has flooded the banking system with reserves. Banks are required to hold a certain percentage of their deposits in the equivalent of a checking account at the Federal Reserve. Like the rest of us, banks do not want to overdraw that account so they always hold a bit more than is required. Those surplus reserves across the entire banking system are called “excess reserves” and they represent the pool of funds available to the banking system to lend to consumers and businesses. Prior to the recession excess reserves typically averaged between $1.0-2.0 billion. Today excess reserves are 1,000 times bigger at $1.5 trillion.

Once consumers and businesses are more willing to borrow and banks become increasingly willing to lend, that $1.5 trillion of surplus reserves could fuel a spending spree the likes of which we have never seen. At some point the Fed has to eliminate, or at least neutralize, banks’ ability to lend out those reserves. The Fed knows that, and has a game plan on how it intends to proceed. Once that process starts, interest rates will begin to rise. The Fed does not see that happening until late 2014. However, it anticipates modest GDP growth for the next couple of years, and sees the unemployment rate declining very, very slowly. If the economy grows more quickly, and the unemployment rate falls more rapidly than the Fed anticipates (more in line with our own forecast), the first rate hike by the Fed will occur much sooner than late 2014. That is unlikely to be a 2012 event, but may well occur by mid-2013.

Keep an eye on excess reserves. Once they begin to fall more rapidly, a series of rate hikes by the Fed will not be far behind.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me