March 10, 2023

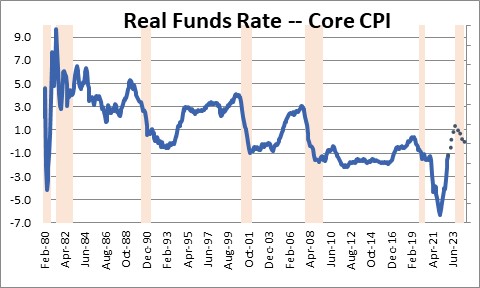

This past week Silicon Valley Bank warned that it was having difficulty and needed to issue additional stock to counter losses on its holdings of securities. That announcement crushed bank stocks and dinged the overall market. This can happen when the Fed rapidly increases interest rates. But is this a one-off event, or is the banking system more fragile than previously believed? The answer to that question is going to depend on the health of the economy. If growth slows appreciably, the banking difficulties will multiply and soon push the economy into recession. We do not buy into that scenario. Clearly growth has slowed but, in our view, the economy is likely to continue expanding at a moderate pace for the rest of the year. Why? Because real interest rates remain negative. Negative real rates are not going to slow growth enough to threaten a recession until much later in this year. By then the Fed will have, presumably, raised the funds rate from 4.75% currently to the 6.0% mark and real rates will finally have become positive. That is likely to produce the long-awaited recession in the first half of 2024. It is coming, but it is unlikely to occur in the absence of further Fed rate hikes.

There can be little difficulty that Silicon Valley Bank is under pressure and there could be at least a few other banks facing similar challenges. But widespread damage to the banking system does not occur in a negative real rate environment. The funds rate today is 4.75%. The core CPI is 5.5%. The real funds rate is negative by 0.75%. But history suggests that the economy does not roll over into recession until that real funds rate has become positive. Thus, in our view, the Fed still has a ways to go before it needs to worry. We suspect that the Silicon Valley Bank fears are not the tip of an iceberg, but by the fall of this year the recession concern will be more warranted.

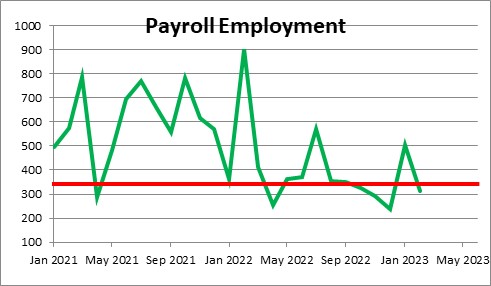

The employment report for February did not reveal any present danger, but it did provide additional evidence that the economy will continue to soften. Payroll employment rose 311 thousand in February and in the past three months has, on average, climbed by 351 thousand. In the first three months of last year employment gains averaged 550 thousand. Hiring has slowed in part because the pace of economic activity has softened,. However, monthly employment gains of 350 thousand remain robust.

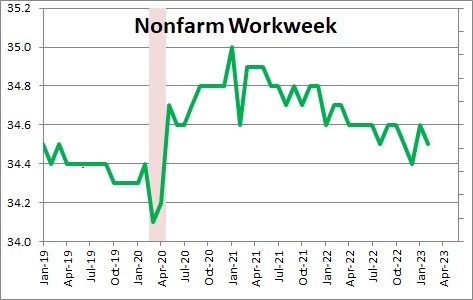

At the same time, as demand softens firms are choosing to work existing employees shorter hours. The length of the nonfarm workweek has fallen steadily since March of last year. It declined 0.1 hour in February to 34.5 hours, but that follows a 0.2 increase in January. Going into the 2020 recession the workweek was at 34.5 hours. It is really hard to interpret its current level as being indicative of a problem. Slower growth, yes, but not a recession.

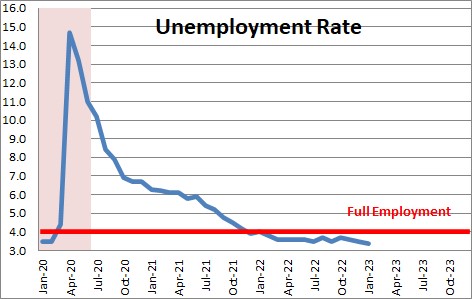

The unemployment rate rose 0.2% in February to 3.6%, but it is important to remember that it surprisingly declined 0.1% in both December and January. It has been hovering around this same level for a year.

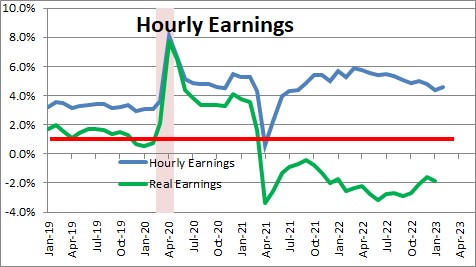

Having said all this, the employment report continued to raise warning flags. Average hourly earnings have risen 4.6% in the past year which in normal times would be a healthy gain. But in today’s world when inflation has surged by 6.5%, real earnings have fallen by 1.9%. Thus, consumer purchasing power has been shrinking. If a consumer goes to the grocery store today and spends $100, he or she might walk away with four bags of groceries. But a year ago they might have been able to leave with five bags.

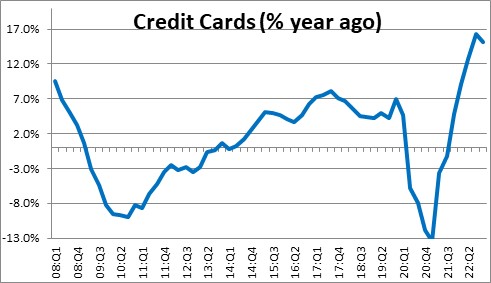

To counter the reduced purchasing power consumers have been relying on credit cards to maintain their pace of spending. In the past year outstanding credit card balances have risen by 15%. That is obviously very rapid and not sustainable.

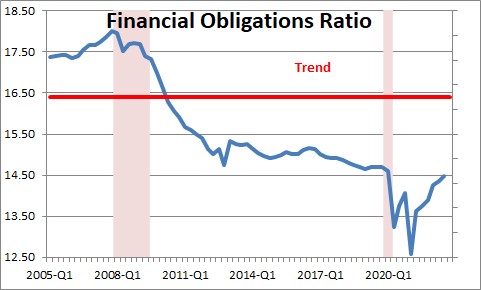

But, thus far, it is not a problem because the consumer had so little debt initially. It appears that consumers used at least some of the stimulus checks handed out in 2020 and 2021 to pay down debt. As a result, monthly financial obligations as a percent of income fell to its lowest level since the 1980’s. The current credit card binge has boosted that debt ratio, but it remains far below its average for the past 20 years. While consumers may not be able to rely on their credit cards forever, they do not seem in danger of being constrained any time soon.

All of this suggests that while the economic outlook has deteriorated in the past year given the extent of Fed tightening, it is not on the cusp of entering a recession. To make that happen the Fed needs to push the funds rate higher to, perhaps, the 6.0% mark by the fall. If, as expected, the core CPI slows to 4.6% by that time, the real funds rate will be positive at 1.4%. That may be high enough to push the economy into a mild recession in the first quarter of next year.

We will need to worry about a recession at some point. But not yet.

Stephen D. Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

“Predictions are hard especially when they are about the future” Yogi Bera

I think the SVB collapse has systemic potential and will lead to a curtailment of loan activity and restrictive risk management actions which could help cool this stubbornly strong economy.

I think 50 bps is off the table and 25 and pause may be the most prudent fed pathway.

My understanding is the massive COVID savings should run out this summer and that too should cool the economy.

Hi Tyson,

You are certainly thinking along the right lines from what I can see. Re: SVP it seems to me, from what I have read, that SVP was being managed differently from other banks. Why regulators did not pick up on this I am not sure. For that reason I think (hope?) the damage from SVP will be relatively contained. I am not thrilled with the guarantee of all its deposits that transpired over the weekend, but I do agree that they have to stop the panic first, and deal with the fallout later.

I also tend to think that this bank would be a good candidate for a sale to someone. It does not have a lot of weird derivatives. It has Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities and, unfortunately, ran into a mismatch problem. Couldn’t one of the big boys buy this thing (at some sort of a discount) and feel fairly comfortable with what they are buying? Solid assets and a sizable deposit base.

I do believe that tech spending is going to slow in the quarters ahead. Tech spending has grown 8.5% in the past year. If firms cannot find enough workers, it seems to me that they have to turn to technology to boost production as an alternative. But the tech sector is going to get dinged by recent events. That, as you point out, should help to slow the economy.

Depending upon what happens in the next week before the FOMC meeting I suspect we will get 25 bps from the Fed. Inflation is still a problem. Given recent events 50 seems out of the question for now. But all of us, including the Fed, need to get a better handle on the fallout from SVP.

Finally, you are right that consumer spending is slowing as they lose the stimulus money. But right now they are turning to credit cards to keep themselves going. That is not sustainable over the long haul, but consumer debt started off so low that it can continue for a fairly lengthy period of time.

Crazy world. Thanks for your thoughts.

Steve

When you hear how much companies had in banks that only had $250,000 FDIC insurance, you wonder how companies like Circle $3.3 bn Roku $487mm blockfi $227mm and Roblox $150mm, it is a wonder that this lack of insurance coverage kept these corporate entities at SVB.

The duration risk should have been something SVB could have wrapped their brains around.

This is a catastrophe because the Feds have all but assured all depositors will be kept whole. That is the moral hazard will be perpetuated and the taxpayer will have to pick up the tab and this will only stoke more inflation going forward.

I cannot independently confirm this but, it is rumored that SVB also did a great great job with DEI (Diversity Equity and Inclusion). I am all for DEI, but if good banking, risk management and fed oversight were compromised through DEI hiring practices, then maybe adding a Q for qualified should be considered.

This regulatory, policy and banking fiasco will hinder tamping down inflation and continue the years of excessive money printing which has spanned from Greenspan’s Fed put to QE… and hinder the years overdue monetary conservativism critical to stanching inflation.

Yes, the poor and elderly suffer most from inflation.

I understand the Wall Street Journal wrote about this risk in November.