June 4, 2021

As each month passes it is clear that the demand side of the economy is showing no sign of slowing down. On the production side, employers are able to hire a respectable number of new workers but they need far more bodies than they are able to find. In addition they are encountering supply constraints. This dichotomy between demand and supply is pushing prices higher. Every economist expects the inflation rate to climb in the short-term and then retreat to a slower pace. But climb by how much? For how long? And then retreat to what? At this point in time nobody can answer those questions. But whatever happens over the next six months, it is unlikely to entice Fed officials to raise rates prior to the end of next year.

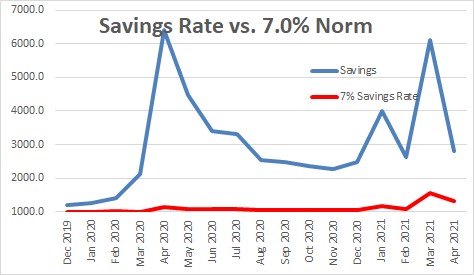

Flush with cash left over from the series of stimulus checks over the course of the past year, the savings rate remains elevated at 14.9% which is more than double its usual 7.0% pace. That leaves consumers with $1.5 trillion more spendable cash than usual. And consumers seem to be in a spending mood.

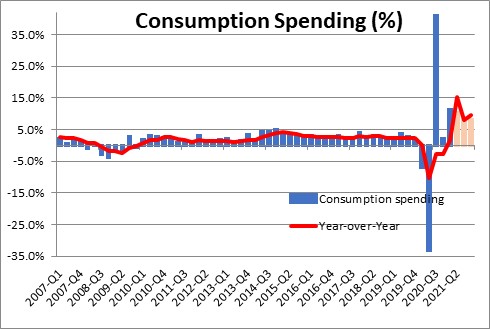

Consumption spending, which is 70% of GDP, climbed 11.3% in the first quarter and second quarter growth should be roughly comparable at 10.5%.

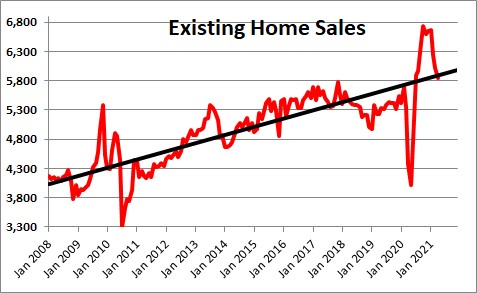

New home sales are at their fastest pace since 2006 and would be even more rapid if there were more homes available for sale. There is currently a 2.4 month supply of homes available for sale which is less than one-half the 6.0 month supply that is required for demand and supply to be in balance.

The demand side of the economy is red hot.

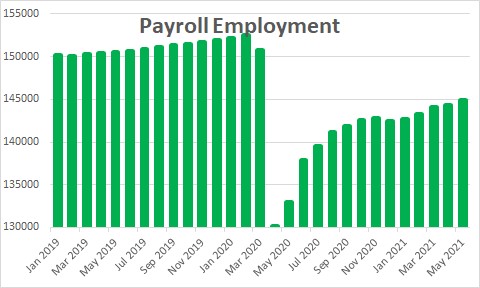

But the production side of the economy is encountering numerous difficulties. High on the list is an inability to hire enough workers to satisfy demand. Payroll employment rose 559 thousand in May which is a respectable increase. But respondents to the purchasing managers surveys for both manufacturing and services almost uniformly cite an inability to hire enough workers.

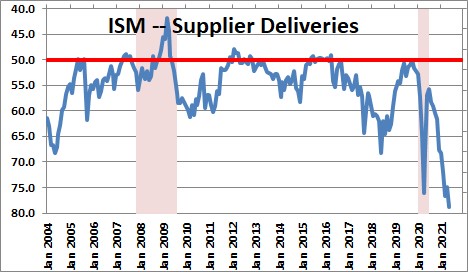

Meanwhile, orders keep rolling in. Businesses produce as much as they can. But the supplier delivery component of the purchasing managers’ survey indicates a record high number of manufacturing and service sector firms are experiencing delays in getting the materials they need for production. Their suppliers cannot get enough workers, or materials, prices have skyrocketed, or there is a backup at the ports. And while a record number of firms are reporting delays in getting what they need, the delays continue to lengthen. The situation, if anything, is getting worse each month – not better.

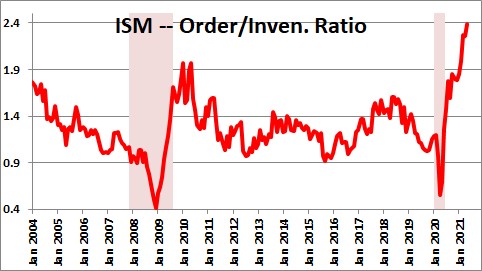

Every month firms have to further deplete inventories to satisfy the demand from their customers. As a result, the ratio of orders to inventories is at a record high level. Somehow firms need to find a way to boost production.

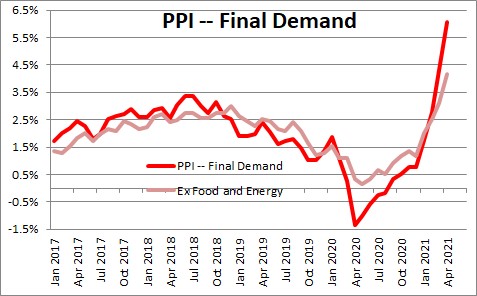

Given this divergence between demand and supply, prices are on the rise. Core consumer prices jumped 0.9% in April. While a single month occurrence so far, is this the tip of the iceberg? Producer prices have registered sizeable increases in each of the first four months of the year. The core PPI rose 1.2% in 2020. The pace has accelerated to 8.0% in the first four months of 2021.

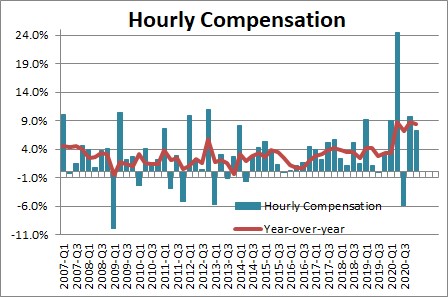

The PPI does not include labor costs. The CPI does. Worker compensation rose 9.7% in the fourth quarter and 7.2% in the first quarter of this year. That is an 8.8% increase in the two most recent quarters. Compare that to the 3.4% increase for 2019 – prior to the pandemic. It certainly appears that firms are having to pay up in the form of higher wages and sign-on bonuses to attract workers and are still unable to get enough of them.

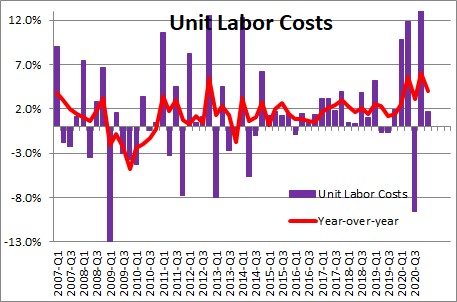

Higher compensation is not a problem if it is matched by a commensurate increase in productivity. If wages and productivity climb at the same rate, workers have earned their pay. But the recent revision to the productivity data reveal much more rapid increases in compensation than had been reported previously. And while productivity is climbing, it is not matching the rate of acceleration in compensation. That means that unit labor costs – labor costs adjusted for the increase in productivity jumped 14.0% in the fourth quarter and an additional 1.7% in the first quarter. That is a 7.9% annualized rate of growth in the two most recent quarters. Compare that to a 2019 pre-pandemic increase of 1.4%.

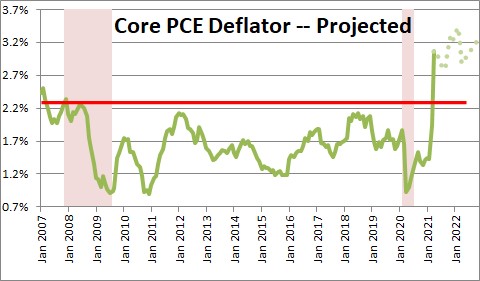

All of this suggests to us that the near-term pickup in inflation could be more troublesome than anyone expects. Thus far market expectations of inflation have not changed too much. The University of Michigan has a 1-year measure of inflation expectations which has climbed to 4.2%. But the bond market believes inflation over the next 10 years will be only 2.4% (the nominal yield on the 10-year note of 1.56% less its inflation-adjusted equivalent of -0.87%). If that expectation is correct, the Fed will be thrilled. It would love to see an inflation rate for the next 10 years of 2.4% or 0.4% higher than its 2.0% target. That would basically make up for the 0.5% shortfall in inflation during the previous 10 years. That is a wonderful outcome, but is it right? We suspect that expectation is too low. We look for a 3.3% increase in the core PCE deflator both this year and next, and fear the projected pace may be far more rapid than what we are expecting. But at this point nobody knows. We have never seen such a wide divergence between the demand and supply sides of the economy so all economists – us included and the Fed — are guessing.

Whatever happens, we believe that the Fed is deeply committed to its current stance which would leave the funds rate essentially at 0.0% through the end of next year. If inflation should turn out to be higher in the near-term, the Fed can fall back on the argument that it expected a temporary acceleration in inflation and that what we are seeing is temporary. And once we get beyond the middle of next year a rate hike any time close to the November 2022 election is simply not going to happen. While the probability is skewed almost exclusively in the direction a faster-than-expected rate of inflation, it would have to be a huge miss to get the Fed off the dime and willing to raise rates.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me