January 29, 2021

The Fed currently pegs the federal funds rate at 0%. Clearly that is a low rate. But exactly how low is it? What might be regarded as a neutral level for the funds rate? It is not an easy question to answer because the neutral rate seems to be changing. The same is true for long-term interest rates. Historically, the yield on the 10-year note has averaged about 2.0% higher than the inflation rate. Today that has shrunk to about 1.0%. Why have these real rates dropped? Where might short- and long-term rates eventually settle?

Whether an interest rate is high or low depends on how it stacks up relative to the rate of inflation. A 10% interest rate most of the time would be regarded as punishingly high. But in the late 1970’s when the inflation rate was 12%, a 10% rate was actually quite cheap. An investor could borrow at 10% for a year, buy an asset whose price would rise 12%, then pay back the 10% loan a year later and actually make money on the transaction. So whether rates are high or low depends upon their relationship to the rate of inflation.

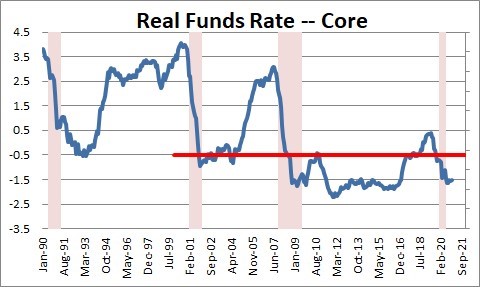

The difference between the funds rate and the inflation rate is known as the real funds rate. Over the past 30 years – since 1990 — the funds rate averaged 1.0% higher than the inflation rate. So for years the Fed regarded a 1.0% real funds rate as neutral. If the Fed wanted an inflation rate of 2.0%, and believed that its policy was neutral when the funds rate was 1.0% higher than that, then a 3.0% funds rate was neutral. But times have changed.

Since 2000 — the past 20 years — the real funds rate has averaged negative 0.5%. If the Fed wants a 2.0% inflation rate and a neutral rate is 0.5% below the inflation rate, then in today’s world a “neutral” funds rate is 1.5%. It is no longer 3.0%.

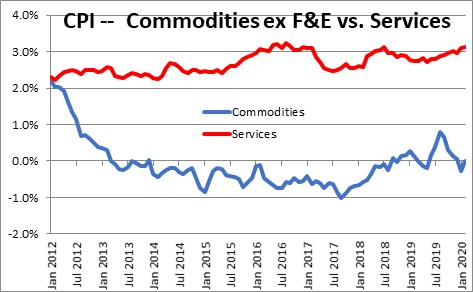

Why would the real funds rate drop? Because technology has gradually lowered the rate of inflation. When we buy anything today, we shop the internet to compare prices. We can find the lowest price available and we will probably buy it from the lowest cost seller. As a result, goods-producing firms in the U.S. today have absolutely no pricing power. Since 2012 goods prices have declined 0.1% while services have risen 2.7%. That is a huge difference. Of all the things that consumers buy, 40% are goods 60% are services. Thus the inflation rate today is about 1.0% lower than it otherwise would have been if technology in the form of on-line shopping did not exist. Given that the inflation rate has consistently been lower-than-expected, the Fed needs much lower rates to produce enough economic growth to lift inflation to the targeted 2.0% pace.

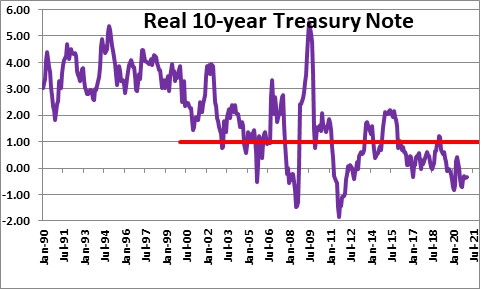

Long-term interest rates are experiencing the same phenomenon. Actual inflation and inflation expectations are lower today than they used to be, hence long-term rates are much lower than one might expect from an historical perspective. In the past 30 years – since 1990 – the yield on the 10-year note averaged 2.0% higher than the rate of inflation. In the past 20 years – since 2000 – the real 10-year rate was 1.0%. If the Fed is successful in boosting the inflation rate to 2.0% then, eventually, the yield on the 10-year note should climb to 3.0%

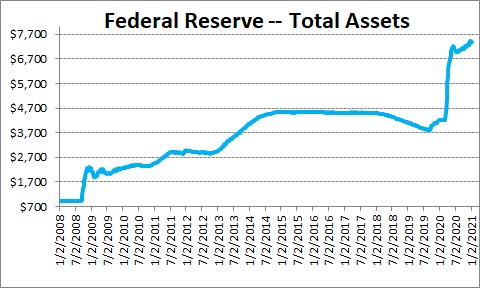

Today we need to be aware that inflation could rise more quickly than expected. The Fed aggressively bought Treasury securities in March and April of last year. It has continued to buy them – but at a much slower pace – every month since then.

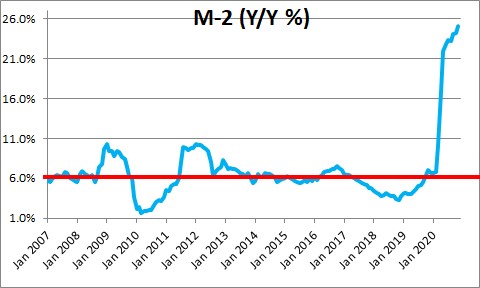

The Fed’s purchases have dramatically increased growth in the money supply. Growth in M-2 has risen 25% in the past year. That is unprecedented. More rapid growth in the money supply is what causes the inflation rate to accelerate. Unfortunately, the lag between the time that money growth accelerates and the eventual increase in inflation is uncertain. It might not show up for a while, or we might begin to see it later this year.

For this reason we expect the core CPI measure of inflation to quicken this year from 1.6% in 2020 to 2.5% by the end of this year and 3.0% by the end of 2022. If that happens the Fed may choose to leave the funds rate at its current level of 0.0%, but the yield on the 10-year note is likely to climb from 1.0% today to 1.4% by the end of 2021 and 1.9% by the end of 2022 and perhaps even higher in the years beyond. So keep your eye on the inflation rate. If it begins to accelerate, long rates in particular are poised to climb.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen, I am currently reading “The Deficit Myth” by Stephanie Kelton. The book is about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). I was wondering what your opinion of this book and theory might be.

Darrel

Hi Darrel,

I have not read her book. Her MMT theory has certainly become controversial. I am not a believer in the concept that deficits do not matter. But I do believe the world has changed that the entire spectrum of interest rates is lower today that any of those rules of thumb I developed throughout my career. Not sure where all of this will settle.

Are you a believer in MMT?

Steve

Stephen,

I am just a curious person who tries to look things from all sides. MMT does seem to make some good sense. However, I am not convinced by it. Thank you for your response.

Hi Stephen,

Thanks for sharing your knowledge with us. Could you explain how did you get these 1.4% (YE 2021) and 1.9% (YE 2022) for 10-year notes?

Lucas

Hi Lucas. Those are my forecasts. The 10-tear is 1.34% currently. It has risen very rapidly — 0.25% the past month. My 1.4% forecast for the end of this year now seems low. F=r the end of 2022 I boosted it to 1.9% on the assumption that inflation picks up somewhat and the Treasury has a giant budget deficit to finance.

For what it’s worth here is the link to my forecasts:

https://numbernomics.com/forecasts/

Steve