November 10, 2023

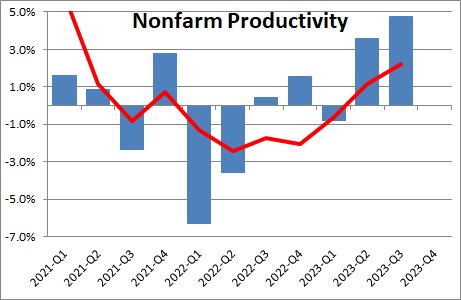

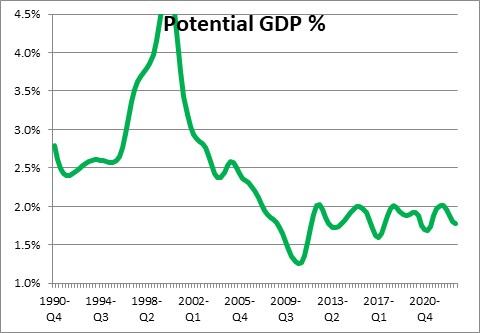

The recent productivity spurt is worth noting and is, perhaps, the beginning of a longer-lasting uptrend. If so, the economy’s economic speed limit could climb from 1.8% today to perhaps 2.5%. Faster potential growth is the holy grail of economics. The economic pie gets larger with bigger slices for both workers and owners. Our standard of living will grow more quickly. But can the dramatic increases in productivity in the second and third quarters of this year be sustained? Many economists are skeptical. We believe that faster growth in productivity just might lie ahead.

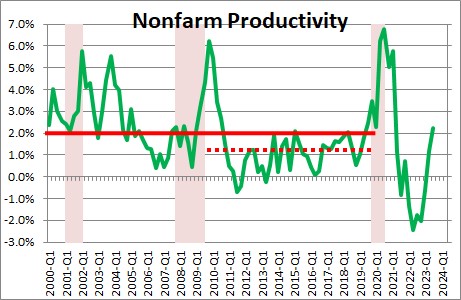

Productivity is simply a measure of worker output per hour. If firms can increase output without boosting the number of hours worked, productivity rises. Productivity growth from 2000 until the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 averaged 2.0%. But from 2010 until the beginning of the pandemic productivity growth averaged 1.2%. It has clearly slowed down in recent years. So, what’s next?

We recently learned that productivity jumped 4.7% in the third quarter of this year. That follows a 3.6% increase in the second quarter. The increase in productivity growth in the past year has been 2.2%. Such an increase is well in excess of the 1.2% pace recorded in the decade just prior to the pandemic. We suggest there are good reasons why faster productivity growth might continue.

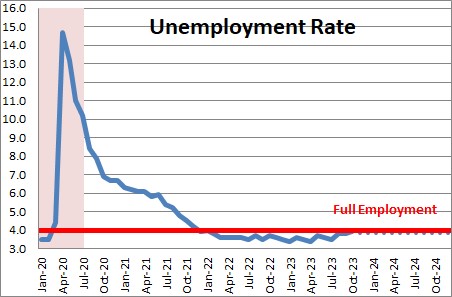

Once the recession ended the unemployment rate fell below the so-called full employment threshold of 4.0% in December 2021. It has been there every month since. The economy has been at full employment for two years. At full employment everyone who wants a job presumably has one. During that time firms of all sizes and in every sector complained that they were having difficulty finding the workers they needed. If the Fed can pull off a soft-landing the unemployment rate will change little between now and the end of 2024. Firms will contend with an exceeding tight labor market for the foreseeable future.

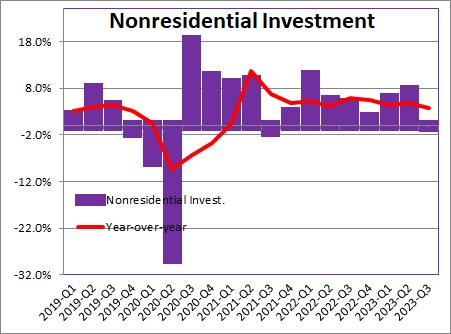

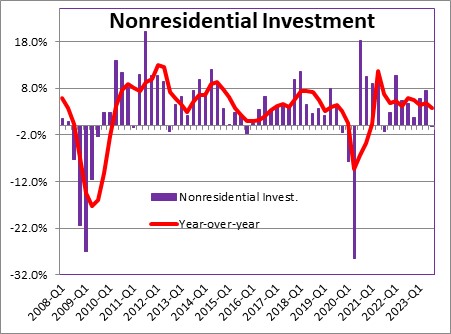

If the economy continues to grow, firms will need to boost output to keep pace with demand. But what if they cannot find an adequate number of additional workers? In the past two years firms have had an incentive to substitute capital for labor. If they invest in technology by purchasing that fancy new piece of software, they can boost output without an increase in headcount. That seems to have happened. In the past couple of years nonresidential investment has grown steadily at a 4.0-5.0% pace. In the most recent year it has risen 3.7%. This is surprising.

During a recession nonresidential investment falls sharply as business leaders lay off thousands of worker, and factories and equipment are temporarily shut down. It happened in 2008-2009 and again in 2020. But once the recession ends the economy recovers quickly, workers are rehired, and investment spending rebounds.

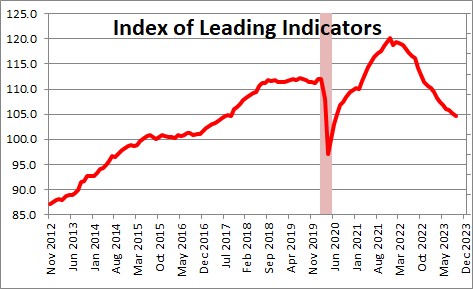

In the past year almost everybody expected a recession to develop in the second half of 2023. After all, the index of leading indicators had fallen every month since December 2021. Surely a recession was on its way. But if the expectation of recession was so widespread, why didn’t nonresidential investment decline? Instead, it has been growing steadily at a 4.0-5.0% pace. We suggest that given the extreme shortage of workers, business people have chosen to spend money on technology to increase production without a commensurate increase in headcount.

If the economy avoids a recession and the Fed achieves its soft-landing, firms will continue to see steady demand for their goods and services. Workers will remain in short supply, which means that firms will spend money on technology to boost output. A dramatic increase in union activity has resulted in outsized increases in wages which should enhance a firm’s desire to substitute capital for labor.

An increase in output with little increase in headcount means that productivity should continue to climb. That in turn means that our economic speed limit will increase.

Currently the Congressional Budget Office estimates potential GDP growth at 1.8%. That represents the economic speed limit. If the economy is at full employment that is as fast as the economy can grow without giving rise to an increase in inflation. That growth rate consists of 0.5% growth in the labor force combined with 1.3% growth in productivity. Going forward the labor force is projected to increase by about 0.5%. But what if productivity growth climbs from 1.3% to 2.0%? In that case potential GDP growth would climb to 2.5% — 0.5% growth in the labor force plus 2.0% growth in productivity. That is not an unrealistic estimate based on history.

Faster potential growth means the economy can grow more quickly without the Fed needing to increase interest rates. For example, if GDP grows at 2.5% and potential GDP growth is 1.8%, the Fed would need to raise rates to slow things down. But if potential GDP growth is 2.5% the Fed would not need to do so. Presumably in that world the funds rate would be about 2.5% (the Fed’s estimated longer-run equilibrium level for the funds rate). Long rates would be about 1.5% higher than the 2.0% inflation rate, or 3.5%.

At the same time, our standard of living (as measured by real disposable income per capita) would grow more quickly with 2.5% potential GDP growth than with 1.8%.

Faster growth in productivity and potential growth are the holy grail of economics. The economic pie gets larger, and both workers and business owners get a bigger slice. It is still early, but this is not an unreasonable expectation.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me