April 18, 2014

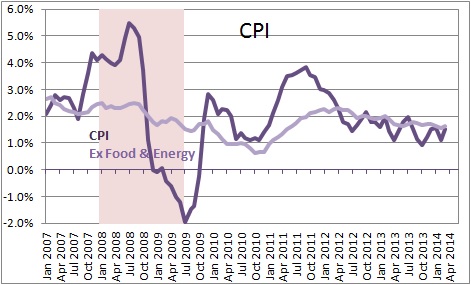

Inflation has been largely ignored for a long time largely because it has been both low and steady. Even though the Fed’s massive bond buying program has created the potential for a pickup in inflation, there has been no hint of higher prices – until now. Thus far the upward tilt to inflation has been limited to the housing sector. But emerging labor shortages may soon translate into higher wages which would exacerbate the situation. However, with the inflation rate currently well below its target and the unemployment rate higher than desired, the Fed does not have to panic if the inflation rate begins to creep upwards. Look for the Fed to raise the funds rate initially in the middle of next year, and to increase it very slowly thereafter.

The core (excluding food and energy) CPI rose 0.2% in March and has risen 1.6% in the past year. While the headline rate is acceptable the details are a bit less friendly.

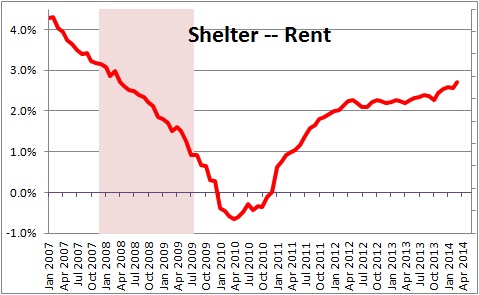

The “shelter” category of the CPI – i.e., rent – has been accelerating slowly for the past several years. At this time last year it was 2.1%. Today it is 2.7%. In the past three months it has picked up to a 3.1% pace. Shelter represents 31% of the CPI so what happens to this category is important.

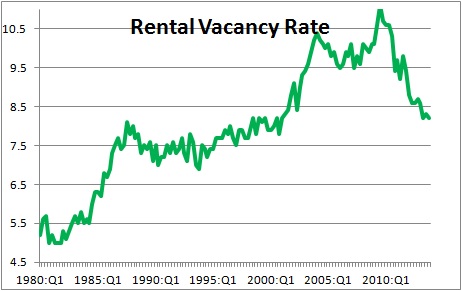

Rents have been on the rise because rental properties are in short supply. The rental vacancy rate has been steadily declining and is now at its lowest level in more than a decade because builders have been unable to keep pace with demand.

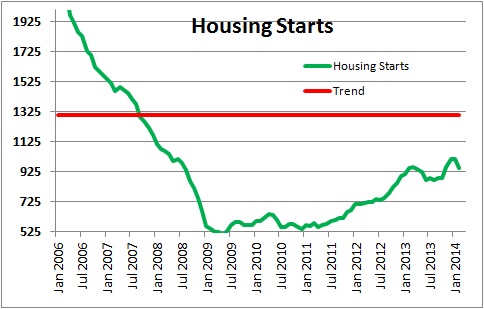

Our economy needs 1.3 million new housing units every year to keep pace with population growth. Housing starts are slightly less than 1.0 million. The pace of production will pick up as the year progresses, but builders are encountering shortages of both available lots and labor which implies that the housing shortage will continue for some time to come.

Furthermore, labor shortages are becoming more widespread. Nineteen states (including South Carolina) already have unemployment rates below 6.0%. Below that level wage pressures begin to emerge. In addition to the construction industry qualified workers are hard to find in information technology, health care, durable goods manufacturing (like autos and aircraft), and oil and gas extraction. Labor shortages are not yet evident in every industry and every community but they are becoming increasingly apparent.

At the same time the factory workweek is at a record long level. Manufacturers are paying unprecedented amounts of overtime. These indicators should lead to both a faster pace of hiring and rising wages in the months ahead. Because labor costs represent two-thirds of a firm’s total cost of production, if wages begin to rise a faster pace of inflation is sure to follow.

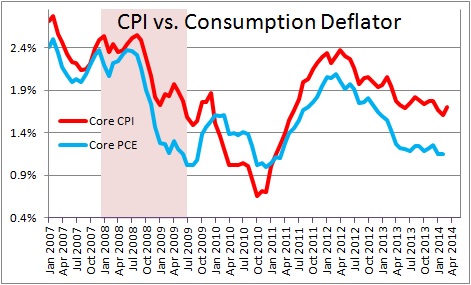

However, the Fed is not alarmed because the current inflation rate is so low. The Fed has an inflation rate target of 2.0%. While the core CPI is currently 1.6% the Fed’s preferred inflation measure, the personal consumption expenditures deflator (excluding food and energy), is rising at a modest 1.1% pace. Both rates will accelerate as the year progresses. We expect the core CPI to rise to 1.9% in 2014, which implies the core consumption deflator will be about 1.5% — still well below the 2.0% target. The fact of the matter is that the PCE deflator is so far below its objective the Fed may actually welcome a bit of an upswing in inflation.

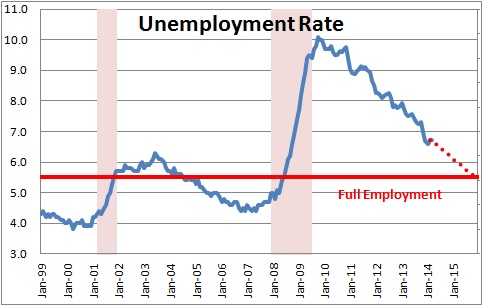

The other measure that is crucial for the Fed in deciding when to raise the funds rate is the unemployment rate. The official rate is 6.7%. But the Fed believes the full employment level is about 5.5%. At that level (presumably) everyone who wants a job has one. The current rate is still far higher than desired.

The Fed has two goals.

- Keep the inflation rate close to the 2.0% target.

- Keep the unemployment rate close to the full-employment threshold of about 5.5%.

With inflation well below the target and the unemployment rate far above it, the Fed will keep the funds rate unchanged until the middle of next year despite some modest upward pressure on the inflation rate.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me