March 28, 2025

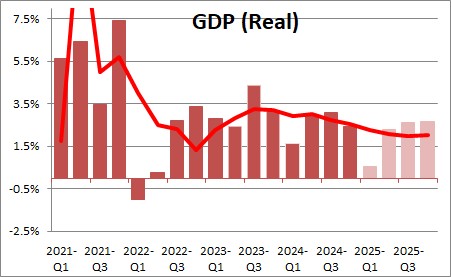

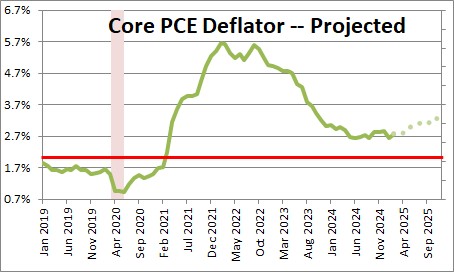

The consumer spending data for February combined with modest downward revisions to earlier months suggest GDP will rise only about 0.5% in the first quarter. A large portion of the first quarter weakness reflects a surge in imports as firms tried to beat the increase in tariffs. But more imports in the first quarter probably means fewer imports – and stronger growth — in subsequent quarters. At the same time, the extremely bad weather in January combined with the devastating fires in the Los Angeles area likely contributed to the slowdown in consumer spending in the first quarter which should also prove to be temporary. Thus one should be cautious about extrapolating too much of the first quarter GDP softness into subsequent quarters. Meanwhile, the core personal consumption expenditures deflator rose more quickly than anticipated in both January and February. This targeted measure of inflation has accelerated somewhat in recent months and is almost certain to grow at a faster pace than the Fed anticipates. While the GDP growth forecast for the year and the inflation outlook remain as murky as ever, it is difficult to see how the Fed could be in a position to ease in the second half of this year.

We have significantly cut our projected first quarter GDP growth rate from 1.5% to 0.5%. Much of the first quarter weakness was caused by a surge in imports as corporate leaders tried to accelerate imports in an effort to beat the imposition of tariffs. The trade component appears to have subtracted about 1.5% from first quarter GDP growth. But if all that has changed is the timing of imports, then the first quarter surge will be offset by reduced growth in imports in subsequent quarters, and the trade component will add to GDP growth in those quarters.

The other component of the weak first quarter GDP growth rate is consumer spending which rose 0.1% in February after declining 0.6% in January. But the miserable, cold, snowy weather in January almost certainly contributed to the spending slowdown in that month. The devastating fires in the Los Angeles area probably exacerbated the drop-off in spending. Given the January and February weakness it is an almost sure bet that consumer spending will be essentially unchanged in the first quarter. That sounds ominous. But the combination of steady job growth, rising wages, and rapid growth in transfer payments (led by Medicare and Medicaid) means that real disposable income (what is left after inflation and taxes) grew 0.3% in January and 0.5% in February. In the past year real disposable income has risen 1.8%, but in the past couple of months it has accelerated to roughly a 3.0% pace. This will provide the fuel for a rebound in consumer spending in the months ahead. Thus, one should be cautious about projecting too much of the January and February spending shortfall into subsequent months. While we expect no change in consumer spending in the first quarter, we anticipate growth in spending of 2.2% or so in the final three quarters of the year.

Given all of the above we project GDP growth of 2.0% in 2025. That is less than the 2.8% pace we expected prior to the beginning of the year, but it is roughly in line with the economy’s potential growth rate. Softer than expected to be sure , but a still solid pace of expansion.

Turning to the outlook for inflation, the core personal consumption expenditures deflator rose 0.4% in February (0.1% faster than expected) after having risen 0.3% in January (revised upwards by 0.1%). The year-over-year growth rate for this core inflation measure is 2.8% which is about where it has been for the past year. The problem is that in the past three months this inflation measure has risen at a 3.5% pace. Even if one envisions a modest slowdown in the months ahead it is hard to see how the core PCE could rise less than 3.3% for the year.

In mid-March the Fed expected the core PCE to rise 2.8% in 2025. If we are right and the pace has quickened to 3.3% and GDP growth for the year is 2.0%, there is no way the Fed will be in a position to ease later this year.

One could argue that in that situation the Fed should actually tighten somewhat in an effort to slow the inflation rate. But we doubt that will happen (we hate to say this) for political reasons. In our opinion, the Fed should have started tightening at the end of 2020 when it became clear that the economy had rebounded dramatically from its March/April slump, and when the breathtaking increase in the inflation rate proved not to be as “temporary” as the Fed had believed. It did not start to raise rates until March 2022. We believe it was about 18 months too late. Perhaps the Fed simply had a lousy inflation forecast and FOMC members firmly believed that the inflation rate would slow. Or perhaps politics entered the equation and the Fed did not want to raise rates quickly and perhaps throw the economy into recession prior to the November 2022 election.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen, what is your opinion about the ever-expanding number of tariffs? It seems they could affect many things from higher prices generally and inflation specifically.

Darrel

Hi Darrel. Sorry about the delay in getting back to you. Back surgery laid me up for a bit. But I’m back (even if my back isn’t)! If you read today’s commentary you can get the basic idea of what I think about tariffs. Basically, you can construct any scenario you want — recession, stagflation, or moderate growth with only a moderate pickup in inflation depending upon what assumptions you make about tariffs. How high? How broad? How long? How do other countries respond? This is a bit like COVID. We do not have any real idea what is going to happen next. We didn’t during COVID. And we don’t now. Nobody has any idea what Trump is trying to accomplish. So what do we do? We read the media and the media are having a field day. Anybody with anything negative to say gets quoted, somebody else picks it up, and suddenly it is gospel. All those bad things could happen, but I am not ready to go there yet. Read this afternoon’s article, see what you think, and let’s talk again.