April 27, 2017

The Fed is raising short-term interest rates. A rising inflation rate is boosting bond yields. The stock market is sinking. Oh, my. Surely, the end of the expansion must be in sight. Wrong! Somehow, we seem to have forgotten about the economic stimulus caused by the tax cuts. In January we thought the tax cuts were great and would boost growth. Now we are worried that the economy is overheating. Step back. Take a deep breath.

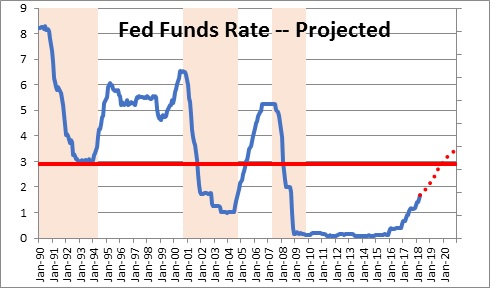

It is true, the Fed is raising short-term interest rates. It started at 0% and has raised the funds rate currently to 1.50-1.75%. We expect two more rate hikes by yearend which would boost the funds rate to 2.0-2.25%. The Fed could choose to raise rates three times if the economy gathers considerable momentum and/or inflation picks up to sharply. Whether it raises rates two or three more times this year is irrelevant. The question is, how high does it intend to go? The Fed expects two more rate hikes this year, another three increases in 2019 raising the funds rate to 2.75-3.25%, and two hikes in 2020 boosting the funds rate to 3.25-3.5%. But keep in mind that the Fed is not “tightening”. It is simply trying to get the funds rate back to “neutral” at which its policy is neither stimulating the economy nor trying to slow it down. That rate is generally believed to be about 3.0%.

How did the Fed come up with a 3.0% rate as a “neutral” level of the funds rate? Over the course of several business cycles the funds rate has averaged about 1.0% higher than the inflation rate. Therefore, for Fed policy to be “neutral” it should probably put the funds rate about 1.0% above the inflation rate. Combining a 1.0% real rate with its 2.0% inflation target implies that a “neutral” funds rate should be about 3.0%.

The Fed expects to reach the 3.0% neutral level by the end of 2019 and then increase the funds rate to 3.5% in 2020. Shouldn’t we worry about that? Not really. Those rates are not nearly high enough to trigger a recession. The Fed had to push the funds rate to 6.5% in 2000 and 5.25% in 2007 before the economy spiraled into recession. If the funds rate is 3.5% by the end of 2020 there is virtually no chance that such a level would be the catalyst for a recession. By that time the expansion will have lasted a record-breaking 11-1/2 years with no end in sight.

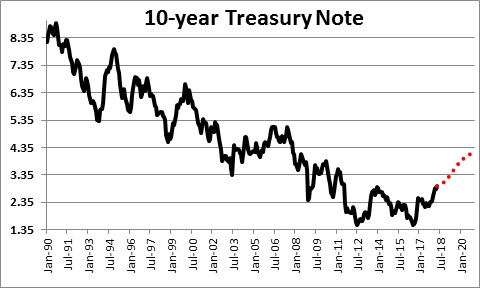

What about long-term interest rates? They recently reached the 3.0% mark. Shouldn’t we worry about that? Nope. Long-term interest rates are determined by two things — the level of short rates and the level of inflation.

With respect to short rates think of it this way. The Fed has raised the funds rate to 1.5%. If the market expected the Fed to keep the funds rate at 1.5% every day for the next 10 years, the yield on the 10-year note would also be 1.5%. It would consist of a very long string of 1.5% overnight rates. If the Fed raises the funds rate to 3.0% the yield on the 10-year note should rise to 3.0%. Thus, there is a link between the level of short rates and long rates.

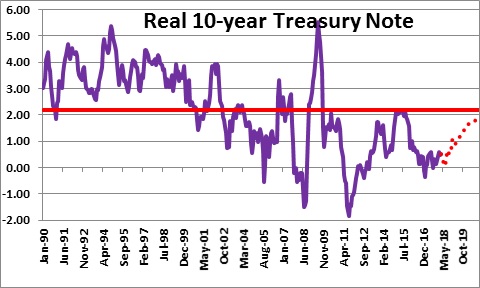

The yield on the 10-year note is also linked to the inflation rate. If investors thought inflation was going to be 2.0% over a 10-year period, for example, they would demand a yield on the 10-year note that was 2.0% higher than the current level of the funds rate. If they thought inflation was going to pick up to 3.0%, they would demand a yield that was 3.0% higher. Thus, there is also a link between inflation and long rates.

How can we determine whether the yield on the 10-year is high or low? During the past several business cycles the 10-year note has averaged 2.2% higher than the inflation rate. With the yield on the 10-year note today at 3.0% and inflation at 2.4%, the real 10-year rate is 0.6% which is very low by any historical standard.

If the Fed keeps the inflation rate at its 2.0% target and the real rate on the 10-year tends to average 2.2% higher than that, the yield on the 10-year should reach 4.2%, by the end of 2020. While the markets have gotten jittery because bond yields have risen to the 3.0% mark the reality is that long rates are going higher in the months and years ahead. But even a 4.2% rate in 2020 should not stall the expansion.

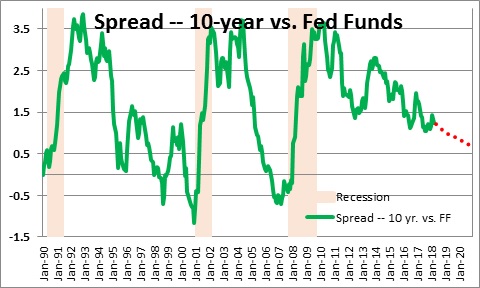

When will rates have risen high enough that the economy could dip into recession? The yield curve — which is the difference between long-term interest rates and short rates — will give us a hint.

With the 10-year yield at 3.0% and the funds rate at 1.7%, the yield curve today has a positive slope of 1.3%. When the Fed tightens aggressively short rates will move higher than long rates and the yield curve will “invert”. When it does that is almost invariably a sign that the economy is about to dip into recession. Note how in both 2000 and 2007 the curve inverted by 0.5% or so six months to one year prior to the onset of recession. If the Fed does what it intends to do and pushes the funds rate to 3.5% by the end of 2020 and bond yields at that time are 4.2%, the curve will still have a positive slope of 0.7%. Not a problem.

If the world evolves as described above, the funds rate will be slightly above its neutral level (3.5% vs. 3.0%) by 2020 which it is not anywhere close to the danger level of 5.25%. Bond yields will presumably be 4.2% which is about average by any historical standard. And the yield curve will have a positive slope of 0.7%. Thus, 2-1/2 years from now there may still be no sign of an impending recession.

Things could go wrong, of course. The economy could suddenly grow very quickly, and/or inflation could climb significantly above the Fed’s 2.0% target. Either of those situations would push the funds rate sharply higher than expected and make the yield curve invert. For us to make a recession call we need to see two things — the funds rate will need to be well above the neutral rate (probably 5.0% or higher), and the yield curve should be inverted. Neither of those conditions seem likely to be met by the end of 2020.

Maintain the faith! The economy will continue to grow. Inflation will steadily pick up but not excessively so. And the stock market jitters will not last long.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

I always enjoy reading your commentary and sure hope you are right.

Thanks Mac. Nice to hear from you.

I keep waiting for some bad things to materialize but, thus far, we keep chugging along. I guess I will remain optimistic for a while longer but at some point the good times will end. Still not sure when that will be.

All the best.

Steve