January 30, 2015

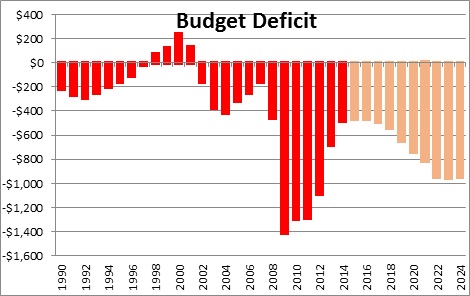

The Congressional Budget Office recently release updated budget forecasts for the next decade. For the next three years it expects the budget gap to remain fairly steady in a range between $400-500 billion which is acceptable. Towards the end of the decade they will once begin to climb and approach $1.0 trillion. That is not acceptable. It would be far preferable for Congress and the White House to take action now to reduce the deficit to avoid more wrenching changes at some point down the road. But because the current deficit today is not a problem there, is virtually no chance of meaningful deficit reduction between now and the 2016 election.

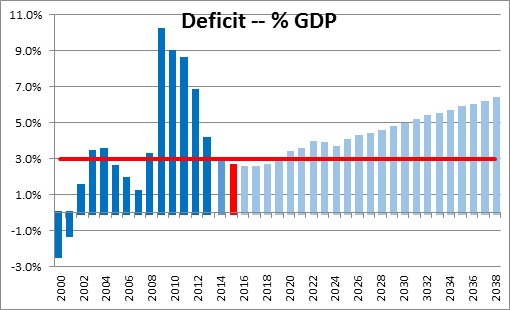

The budget deficit for fiscal year 2014 was $483 billion and the CBO expects it to shrink ever so slightly to $467 billion this year. This year’s projected deficit is 2.6% of GDP. Economists believe a budget deficit that is 3.0% of GDP is sustainable. The CBO expects the budget deficit to remain below the 3.0% mark for the balance of this decade as the economy continues to expand at a relatively brisk pace. But beyond 2020 the deficit once again begins to climb and approaches $1.0 trillion. This widening budget gap is driven by demographics. As increasing numbers of baby boomers reach retirement age they begin to collect Social Security benefits and become eligible for Medicare.

The budget problem intensifies dramatically in the years beyond the CBO’s current 10-year forecast horizon. Once a year the CBO produces a much longer 25-year budget forecast. Last year’s projection was ominous. Beginning in 2020 the projected budget deficits climb above the acceptable 3.0% mark and reach 6.3% of GDP by 2039.

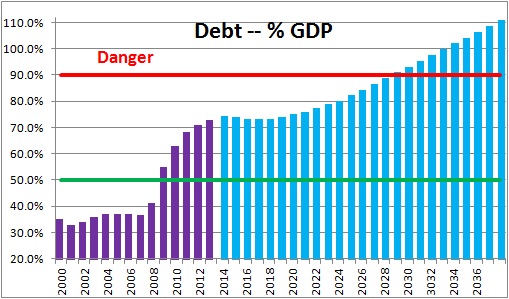

To finance the budget deficit for any given year the Treasury must issue an equivalent amount of debt to finance it. For example, if the budget deficit is $1.0 trillion the Treasury must issue $1.0 trillion of debt to finance the deficit. The problem with persistent deficits is that their impact on debt outstanding is cumulative. If the Treasury issues $1.0 trillion of debt to finance the budget deficit in year one and faces another $1.0 billion shortfall in year two, by the end of that second year the debt outstanding has climbed to $2.0 trillion.

Using the Treasury’s long-term budget projections from July of last year the steadily yawning budget gaps beyond 2020 begin to take their toll on debt outstanding as a percent of GDP. it steadily climbs and reaches 107% of GDP by 2039. Economists generally regard anything above the 90% mark as problematic for a couple of reasons. First, the annual interest payments used to finance the budget deficit become an increasingly large percentage of GDP. Second, government spending becomes so large that it becomes difficult for corporations to raise the funds they require for investment. Third, foreign investors may start to worry about a country’s ability to repay that debt. Because foreigners own about one-third of all U.S. Treasury debt outstanding any cutback in their willingness to hold Treasury debt would be problematic.

That is the good news. The bad news is that the CBO does not incorporate any recessions into its projections. The current expansion began in July 2009. The longest expansion on record lasted exactly 10 years. So beyond the middle of 2019 the economy is probably on borrowed time. During a recession the budget deficit widens dramatically. Revenues decline as the economy dips into recession. Government spending increases as unemployment, welfare, and Medicaid benefits climb. Thus, a debt to GDP forecast of 107% by 2039 probably represents a best case scenario. With slightly less optimistic assumptions a debt to GDP ratio of 150% is possible.

To put this in context, Greece’s debt to GDP ratio is currently 165%. That is probably not the kind of company we want to keep.

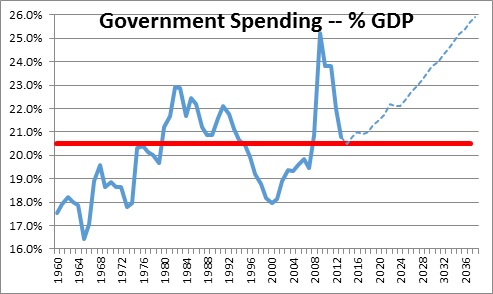

These projections are not cast in stone. Congress could take action to alleviate the problem. Taxes could be raised, spending could be reduced, or some combination of the two. In this particular case the problem is concentrated on the spending side as government expenditures climb far above the 20.5% average pace of government spending for the past 50 years. The baby boomers are at the heart of the problem. Thus, it is clear that somewhere along the line government spending, entitlement spending in particular, must be cut. Unfortunately, with budget deficits likely to be kept in check for the next several years, there is virtually no chance that Congress and the White House will accomplish any meaningful deficit reduction between now and the 2016 election. Too bad. No action today means that far more onerous cuts will be required in the years ahead.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Stephen,

Thank you for the most depressing news you have stated for a long time. I see why it is true and at this point in time, it is difficult to see how Congress is either going to raise taxes or cut expenditures. Not to mention, how the government will be able to borrow the funds to keep up with the problem.

My hope parallels where the country found itself after the Civil War. It would have appeared that the US was going to literally implode, but onto the scene came oil, engines, cars, electricity, airplanes and gadgets of every kind and size etc., etc., and guess what, the predictions of doom turned around into reality of success. Maybe there are those kinds of unexpected phenomena that will appear and take us down pathways we have not predicted in the next 20 years or so.

O.K., I am the eternal optimist. The alternative is a high bridge with a long fall and a fast stop. I am not going there.

Thanks for your insights. I really enjoy reading them.

…Darrel Staat