April 13, 2018

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) this week completed its annual 10-year projection of budget deficits and federal debt outstanding for 2018-2028. This exercise is typically completed in January but was released later than normal this year to give CBO an opportunity to fully evaluate the combined effect of the tax cut legislation enacted in December of last year and the Budget Act passed in February. Given CBO’s preliminary estimate late last year that the tax cuts would increase budget deficits by a total of $1.5 trillion over the next ten years, it is not surprising that its final forecast shows a significant erosion in the budget outlook.

CBO acknowledges that their projections for the upcoming 10-year period are subject to more uncertainty than usual. The issue centers largely on the extent to which the recent tax cuts – the corporate tax cut in particular– will stimulate investment spending and the country’s potential GDP growth rate. CBO estimates that potential growth will quicken from the 1.5% pace registered in the 2008-2017 period, to 2.0% for 2018-2022 but slip back to 1.8% between 2023-2028. We are more optimistic and envision a pickup in potential GDP growth to 2.8% or so by the end of this decade.

The reality is that nobody knows which view may be more correct. Thus, budget projections beyond the next couple of years should be viewed cautiously. Having said that, the direction and general magnitude are clear. The recent policy changes have boosted budget deficits significantly which will, in turn, increase the amount of debt outstanding. Both deficits and debt will climb to unsustainable levels. The United States had a problem with budget deficits and debt outstanding prior to the recent policy changes, and the forecasts have gotten worse even though the exact dimensions of the erosion have yet to be determined.

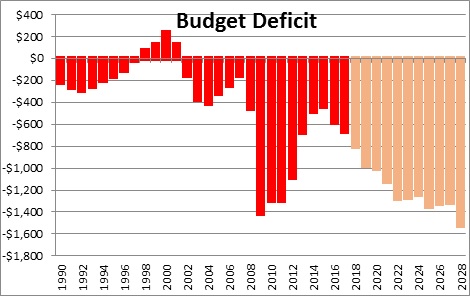

In June of last year, the CBO estimated that the fiscal 2018 budget deficit would be $563 billion. It now expects it to be $804 billion as tax cuts have reduced tax revenues and an increase in defense spending has boosted government expenditures. Last June the CBO thought that the budget deficit would not climb to the $1.0 trillion level until 2021. Now it thinks that is likely to happen next year – fiscal 2019 – and expects the deficits to climb further to $1.5 trillion by 2028.

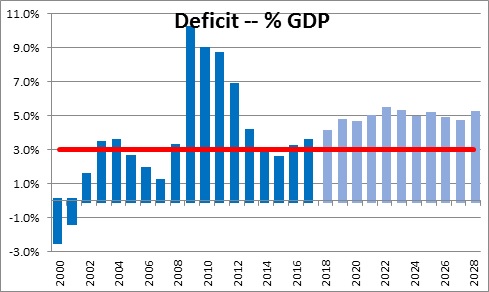

Those are eye-popping, and disturbing, numbers. But the best way to evaluate them is to calculate the projected deficits as a percent of GDP. Economists believe that the U.S. can run a sustained budget deficit that is about 3.0% of GDP. In fact, deficits for the past four years have been in that general ballpark. But within two years the projected deficits will climb to roughly 5.0% of GDP. The actual deficit estimates are the same as shown in the chart above, but a deficit that is 5.0% of GDP sounds somewhat less threatening. It is not. It is still troubling.

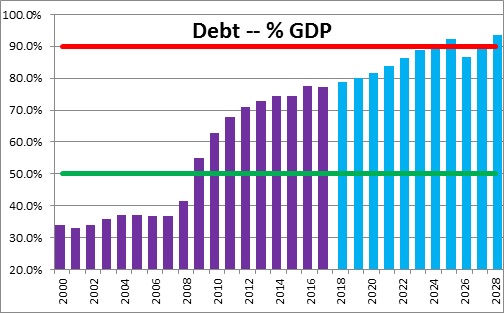

Keep in mind that every year that the government runs a budget deficit the Treasury must issue an equivalent amount of debt to finance the budget gap. Hence, a $1.0 trillion budget deficit in any given year will increase the amount of debt outstanding by $1.0 trillion. A string of $1.0 trillion deficits will boost debt outstanding by $1.0 trillion each year! It is cumulative.

The deficits indicated above will lift Treasury debt outstanding as a percent of GDP from 76.5% last year to the 96% mark by 2028. Economists suggest that a debt to GDP ratio of 50% is sustainable. But once the debt/GDP ratio climbs to 90% it can be a problem. Debt holders, particularly foreigners, may question the willingness and/or the ability of the Treasury to pay its future debt obligations. That is especially true if projected budget deficits beyond the forecast period lift the debt/GDP ratio even higher. With the deficit projected to be $1.5 trillion in 2028, deficits are certain to persist well beyond the forecast period and the debt/GDP ratio will continue to climb.

The Treasury’s 30-year budget forecast should become available sometime around midyear. Last year it had the debt/GDP ratio climbing to 127% by 2030 and 155% by 2047. That is far beyond the 90% danger threshold. The recent revisions are certain to push those estimates higher. To put those numbers in context, Greece is expected to have a debt/GDP ratio this year of 184%. The U.S. is not Greece. But to allow debt outstanding to climb to the percentages noted above is irresponsible. The U.S. has a budget deficit and debt outstanding problem that is on the verge of spiraling out of control. It needs to address the problem at some point, but it probably will not do so until it becomes a crisis. What is clear is that the issue will not be addressed by this president.

Stephen D. Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me