July 30, 2021

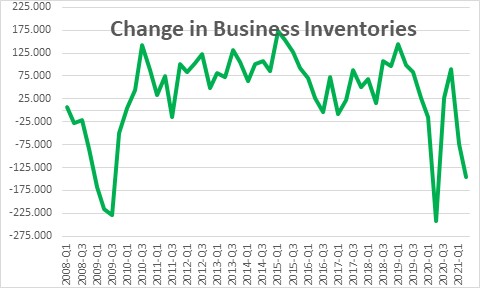

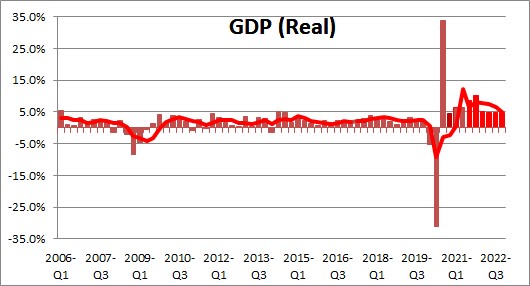

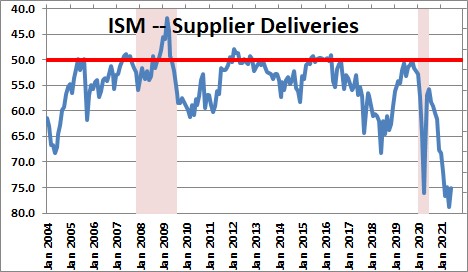

The biggest news about second quarter GDP was not the slower-than-expected 6.5% GDP growth rate but the extent to which businesses needed to dip into inventories to satisfy demand. Inventories fell $146 billion in the second quarter. Declines of that magnitude typically occur in the first quarter or two of a recovery. But this drop occurred a full year after the recession ended in April of last year. The drop highlights the extent to which there is an imbalance between the demand and supply sides of the economy. Firms of all sorts are being challenged to find enough workers, and are being forced to curtail production as supply side constraints negatively impact their ability to produce. But in the months ahead there should be an increasing supply of workers as the generous Federal unemployment benefits expire after Labor Day, and businesses gradually find ways to work around the supply chain disruptions. Thus, the significant depletion in inventories in the second quarter will lead to faster GDP growth in the quarters ahead as firms step up the pace of production and restock their shelves.

Nonfarm business inventories declined by $146 billion in the second quarter. Typically inventories drop as the economy turns the corner from recession to expansion. Consumer confidence returns and they quickly become willing to spend. But businesses are unable to ratchet up production quickly and are forced to dip into inventories to satisfy demand. We saw a similar decline in inventories in the second quarter of last year. The February/March 2020 recession ended in April as stimulus checks turned the economy upwards in that month. With cash in our pocket we went on a spending spree. After laying off 22 million people in March and April, firms simply could not boost production fast enough to satisfy the demand. Inventories in the second quarter of last year plunged by $242 billion. We saw similar declines in the third and fourth quarters of 2009 as the long, deep 2008-09 recession came to an end.

But then what happens? Firms begin to hire freely. They work their employees longer hours. They boost production and are eventually able to restore their depleted inventories. That happened in 2010 and again in the third and fourth quarters of last year. To get inventories back to the point where they stop falling will add 2.2% to GDP growth in the quarters ahead. Most likely inventory restocking will add at least a percentage point to growth in each of the last two quarters of the year. So while 6.5% GDP growth in the second quarter was slightly below the market’s 8.5% expected pace, it would be a serious mistake to interpret that as a sign that the pace of economic expansion is slowing.

For what it is worth, we expect GDP to climb 8.5% in the third quarter and 10.5% in the fourth quarter. As federal unemployment benefits expire after Labor Day there should be a big jump in both the labor force and hiring in the fourth quarter. At the same time businesses should find ways to work around their inability to get raw materials. As that happens, they will boost both production and GDP growth, and lift inventory levels into better alignment with sales.

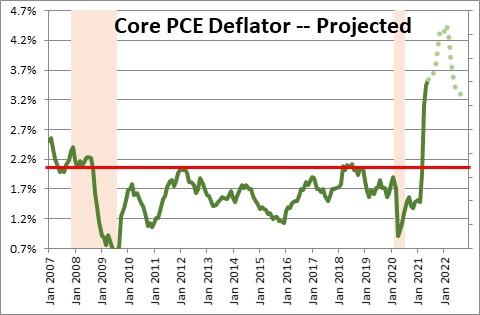

Not surprisingly, the excessive demand for goods and services is boosting the inflation rate. The core personal consumption expenditures deflator rose 0.4% in June after rising 0.5% in May and 0.6% in April. In the past year this inflation measure has risen 3.5%, but in the past three months the pace has accelerated to 6.5%. Last month the Fed said it expected the core PCE deflator to rise 3.0% in 2021 and return to 2.1% in 2022. Good luck with that. We estimate inflation gains of 4.3% in 2021 and 3.3% in 2022.

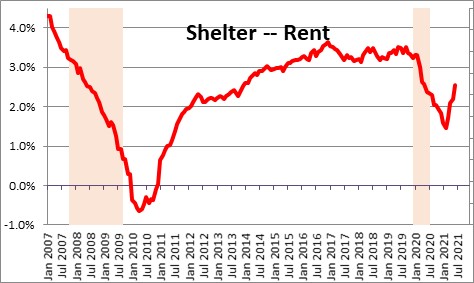

It seems odd to us that the Fed continues to believe that the quickening of inflation has been caused entirely by temporary factors such as restaurants, hotels, and airlines returning their prices to pre-pandemic levels. Those prices are climbing rapidly but will eventually slow down. But what about the shelter component? House prices have climbed almost 20% in the past year. It is a sure bet that house price appreciation of that magnitude will boost rents. And it has. The shelter component of the CPI is quickening. Its year over year growth rate of 2.6% is not threatening, but in the past three months the pace has climbed to 4.8%. We have not experienced that kind of growth in the shelter component in the past 15 years. That is a big deal because the shelter component represents one-third of the entire CPI. What is happening to rents is not temporary. How can the Fed feel so comfortable concluding that the inflation pickup is temporary? That makes no sense.

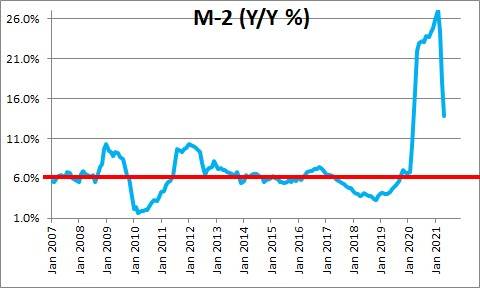

It is also puzzling to us that the Fed never even mentions growth in the money supply as a potential factor boosting the inflation rate. But 13.8% M-2 growth in the past year is more than double its average growth rate for the past 20 years. And as long as the Fed continues to purchase $120 billion of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities every month, M-2 will climb at roughly that same pace and inflation will grow far more rapidly than the Fed suggested in June. It is time for the Fed to rein in its wildly stimulative monetary policy.

It is moving in that direction but far too slowly. It continues to discuss when to begin tapering its purchases of securities and how quickly. It will, most likely, not even get started on that path until the early part of next year, and it will not finish tapering until the end of 2022. The first time we might think about an actual increase in interest rates still seems to be 2023. While a few Fed officials share our view that it should begin to reduce its purchases of securities immediately, the vast majority are not in that camp. Is the Fed making a policy mistake? We think so.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C

Follow Me