July 14, 2017

The economy’s speed limit has slipped from 3.5% during the 1990’s to 1.8% today. That growth rate can be estimated by adding the growth rate of the labor force to the growth rate of productivity. We have long argued that with so many baby boomers retiring that little could be done to stimulate growth in the labor force during the next decade. Hence, the only viable way to boost potential growth was via increased corporate investment which would boost the growth rate of productivity. But in a recent speech Fed Chair Yellen suggested that the U.S. could adopt policies designed to encourage women to work, boost labor force growth, and lift potential GDP growth in the United States. Could potential growth rebound to the 3.5% pace seen in the 1990’s? Perhaps.

Potential GDP growth represents the sum of two numbers – the growth rate of the labor force and the growth rate of productivity. In the 1990’s the labor force was zipping along at 1.5%, productivity growth was 2.0%. Add them up and the economy’s potential growth rate was 3.5%. Today labor force growth has slipped to 0.8% while productivity has slowed to 1.0%. Thus, potential growth today is 1.8%. But it does not have to be 1.8% forever. Policy measures can help.

With respect to the labor force side of the equation, when baby boomers retire they drop out of the labor force. Given that the boomers will continue to retire for another decade we have argued that there is little chance for a pickup in the growth rate of the labor force. Janet Yellen disagrees.

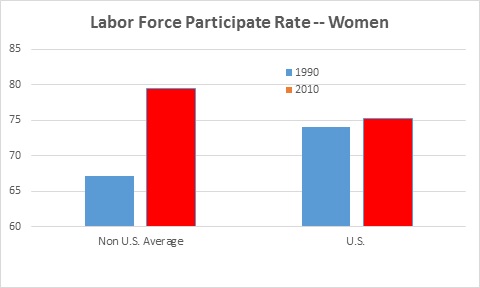

Citing a Cornell University study released in 2013 by Francine Blau and Lawrence Kahn, Yellen pointed out that between 1990 and 2010 the participation rate for women rose dramatically throughout Europe, but in the U.S. it was essentially unchanged. For example, the non-U.S. average climbed from 67% in 1990 to 79.5%. Furthermore, the pickup in female participation was widespread – Canada, Australia, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain all experienced a double-digit gain. Meanwhile, in the U.S. the female participation rate edged upward from 74% to 75.2%. The survey included 22 countries. In 1990 the U.S. ranked #6. By 2010, it had dropped to a shocking #17. Participation rates elsewhere not only caught up with the U.S., they surpassed it.

This result was no accident. It came about because of family friendly policies designed specifically to incorporate women into the labor force. Some women choose to drop out of the labor force to raise their offspring. But others would like to work but the financial strains of doing so prevent that from happening. Those women represent untapped potential GDP growth.

- Paid maternity leave. In the U.S. employers must provide 12 weeks of unpaid maternity leave. Elsewhere, maternity benefits were longer and usually paid. During the survey period outside the U.S. these entitlements rose from 37.2 weeks to 57.3 weeks. Having the right to get their job back almost certainly raises the job prospects who those women who leave the labor force during childbirth. But several questions arise. Does offering such a benefit encourage women to remain out of the work force longer than they otherwise would? Does the employer benefit? During leave time the employers must pay the person on leave as well as her replacement. This raises the expected cost of employing women of childbearing age.

- Right to work part time. During the survey period many European countries adopted policies that give women the right to demand a change to a part-time work schedule. Clearly this is a benefit to women. But would employers be less willing to hire in a woman in the first place given that at some point down the road she could demand such a benefit?

- Publicly provided child care services. Such a benefit would be attractive to women because it reduces the cost of working outside the home. And, unlike the part time benefit, it would not increase the employer’s cost of hiring women for part time positions.

Yellen noted that “policy differences – in particular, the expansion of paid leave following childbirth, steps to improve the availability and affordability of childcare, and increased availability of part-time work – go a long way toward explaining the divergence between advanced economies.” And, “if the United States had policies in place such as those employed in many European countries, female labor force participation could be as high as 82%.”

But will higher labor force participation rates among women boost potential GDP? Ms. Yellen thinks so. A Fed study concluded that between 1948 and 1990 the rise of female participation contributed about 0.5% per year to the potential growth rate of real gross domestic product.

So what might happen to potential GDP growth? Suppose for a moment that the policies described above by Fed Chair Yellen boost labor force growth by 0.5%. Let’s further assume that the combination of Trump’s proposed corporate tax cuts, repatriation of earnings, and a reduced regulatory burden boost productivity growth by 1.0% (which we have described in previous articles). These policy changes would raise potential GDP growth by 1.5% from 1.8% currently to 3.3% or so. That puts it back close to the glory decade of the 1990’s. The economy may not be able to grow quickly today, but it can surely resume vigorous growth if our policy makers in Washington can get with the program.

Stephen D. Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me