August 9, 2024

Following the release of several soft data points highlighted by the June employment report, the market quickly concluded that a recession is imminent and the fixed income market priced in a full percentage point of Fed rate cuts by December. Given this fear the stock market plunged. But this exact same thing happened last year. In mid-2023 almost every economist expected a recession by the end of 2023 as high interest rates took their toll and the recession fear triggered a stock market correction. Despite the angst GDP growth turned out to 4.9% in the third quarter and 3.4% in the fourth quarter. Some recession. Here we go again. Like last year there are some indications that the pace of expansion is slowing, but it is not collapsing. There is no reason for the Fed to panic. Having said that, rate cuts of 0.25% at each of its final three meetings of the year seem warranted. Growth is slowing, inflation continues to retreat, and the real funds rate is high enough that the Fed can afford to gradually reduce it and bring it into closer alignment with a neutral rate.

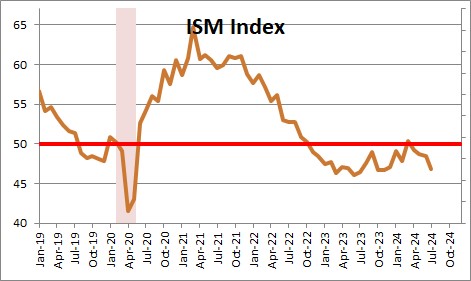

The trouble began when the Institute for Supply Management published its monthly index of activity in the manufacturing sector for July. It fell 1.7 points to 46.8. This was the fourth consecutive decline from its recent peak of 50.3 in March. Economists can easily dismiss a single month of soft data, but it is harder to shrug off four consecutive declines from a generally well-regarded indicator. A level of 50.0 is the breakeven point. Below 50.0 the manufacturing sector is shrinking, but the ISM group says that a level of 42.5 is typically associated with a recession for the economy as a whole. The direction is troubling.

A couple of things happened that may have weakened the July data. The first was a cyberattack on computer software in late June that disrupted business operations for thousands of automobile dealerships for more than a week and resulted in a 5.1% drop in car sales for that month.

Second, on July 1 Hurricane Beryl became the earliest Category-5 storm on record. After causing catastrophic damage to several islands in the Caribbean, it plowed into Texas and Louisiana several days later and continued on a northeast path through the Midwest and the Northeast.

It is hard to imagine that this combination of events did not have at least some negative economic impact on a large swath of the country.

Two days later the July employment report confirmed the apparent slowdown. Payroll employment rose 114 thousand, the workweek declined 0.1 hour, and the unemployment rate rose 0.2% to 4.3%. Those three pieces of information indicated considerable labor market weakness in July. But what if the July results were biased downward by the combination of the two events described above? Economists could easily project the July weakness into subsequent months – given that is what they already feared — and jack up the possibility of a second half recession.

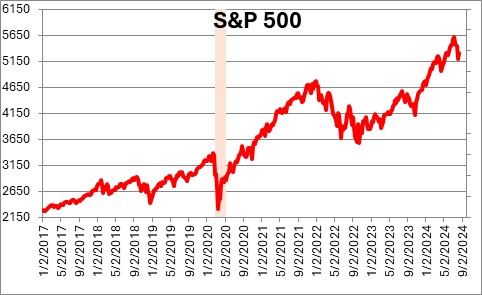

These data generated panic in the stock market and resulted in a kneejerk 10% correction. Given a few days for further reflection, the stock market has settled down and recovered about one-half of its earlier drop.

We are less concerned. For what it is worth we anticipate GDP growth of 0.9% in the third quarter and 1.6% growth in the fourth quarter of the year. That sounds quite weak, but a large part of the slowdown reflects a reduced pace of inventory accumulation. Final sales growth, which excludes the change in inventories, is expected to be 2.2% and 1.7% — a far less troublesome outcome.

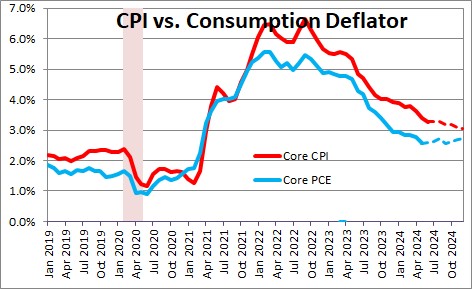

On the inflation front, both the core CPI and the core personal consumption expenditures deflator are likely to be relatively steady between now and yearend. The core CPI, for example, is 3.3% today and should inch lower to 3.1% by yearend. The core PCE deflator is 2.6% currently and should edge upwards to 2.7% by December. But both inflation measures should resume their downtrend in 2025 and be at or close to their 2.0% targets by the end of that year.

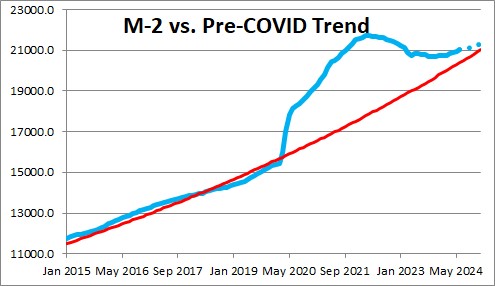

We feel confident about the downward path of inflation because the Fed continues to slowly shrink its balance sheet and thereby reduce the remaining amount of surplus liquidity in the economy. At the moment there appears to be about $0.6 trillion of surplus liquidity. That should disappear by yearend. As that occurs, disinflation will continue.

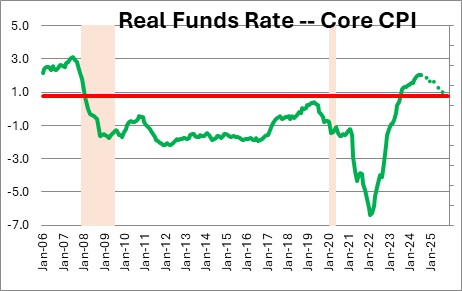

Against this background, the Fed can initiate a long series of gradual reductions in the funds rate. The way to measure the degree of tightness in Fed policy is by examining the real funds rate. The fed funds rate today is 5.3%, the core CPI is 3.3%. Thus, the real funds rate is the difference between those two numbers or +2.0%. The Fed believes its policy is neutral when the funds rate is 0.8% higher than the funds rate. Thus, Fed policy today is restrictive – which is what it should be given that inflation remains far above target. But with the economy slowing down to some extent (exact amount to be determined), and the inflation rate likely to continue to diminish further in the months ahead, the Fed can begin the long-awaited series of rate cuts. We expect that by yearend the Fed will have lowered the funds rate by 0.25% three times which reduces it to 4.6%. The core CPI should be 3.1%. Doing the subtraction implies that by yearend the real funds rate will be 1.5%. That is still higher than the 0.8% the Fed believes is neutral and paves the way for additional rate cuts in 2025.

The bottom line is that economists once again this year are misreading the economic tea leaves. The economy appears to be slowing but it is not collapsing, the inflation rate will continue to shrink, and the Fed will soon begin a long string of rate cuts. The Fed has no need to panic. One of these days economists will learn not to understate the degree of strength and resilience of the U.S. economy. Today is not that day.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me