March 22, 2019

In January Fed Chair Powell signaled that Fed policy would be on hold for a while. Most economists thought that meant no rate hike through midyear, but with two rate hikes possible in the second half the funds rate would reach 2.9% by yearend. On Wednesday the Fed said it expects the funds rate to remain at its current level of 2.4% through yearend. What happened?

At the press conference Powell talked about slowing job growth, weaker than expected retail sales, investment falling short of last year’s pace, and sluggish growth in Europe and China. The Fed seems to believe that the economic impact from these factors will be relatively long lasting. As a consequence, it trimmed its 2019 GDP forecast from 2.3% to 2.1%. Maybe the Fed is right, but we envision a more temporary slowdown. Following 1.5% GDP growth in the first quarter, we expect growth of 3.0%, 2.8%, and 2.9% in the final three quarters of the year. As a result, we anticipate growth of 2.6% in 2019 versus the Fed’s 2.1%. While we may be too optimistic, it is just as likely that the Fed is too pessimistic.

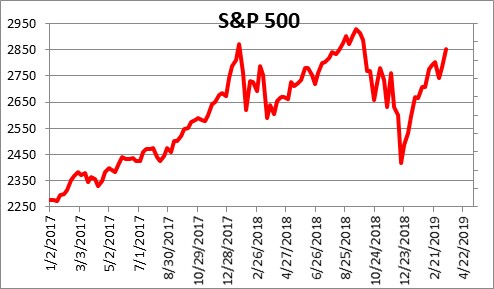

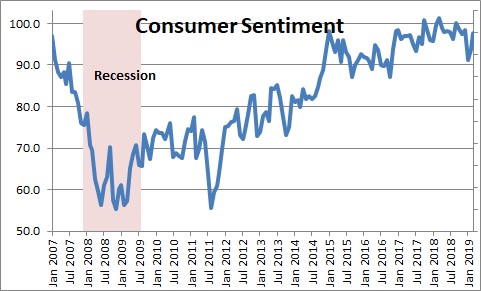

We attribute most of the December and January drop-off to the precipitous 20% decline in the stock market, the Fed’s rate hike in December combined with an expectation of two additional rate increases in 2019, compounded by the negative impact on growth associated with the government shutdown.

But the stock market is now within 3.0% of erasing its fourth quarter drop and reaching a new record high level.

Consumer sentiment has bounced back sharply. Job gains in the past three months have averaged 186 thousand which should boost income and permit consumers to spend at about a 2.5% pace this year.

The Institute for Supply Management indexes of activity for manufacturing and non-manufacturing firms have slipped from their previous lofty levels but are consistent with GDP growth in excess of 3.0%. Mortgage rates have fallen 0.5% since the end of last year to 4.4%. And in April there is a good chance that the U.S. and China will come to some sort of a trade agreement which would remove yet another obstacle to both U.S. and global GDP growth.

Thus, we think there is a plausible case that as the year progresses GDP will register relatively vigorous 2.6% growth for the year and the core CPI inflation rate will climb to 2.3%. The Fed expects core inflation of 2.0%. Could this combination of faster-than-expected GDP growth and more-rapid-than-anticipated inflation cause the Fed to regroup and raise rates by yearend? No.

Fed Chair Powell talked at some length about inflation having consistently fallen short of the Fed’s 2.0% target. “That gives us the ability to be patient and not move until we see that our target goals are being achieved.” That suggests that, if anything, the Fed may welcome a period of inflation that is somewhat above target. Thus, it is very difficult to envision the funds rate above its current 2.4% pace by the end of this year regardless of who is right. The Fed envisions one rate hike in 2020 which would boost the funds rate to 2.6% with no change in rates thereafter

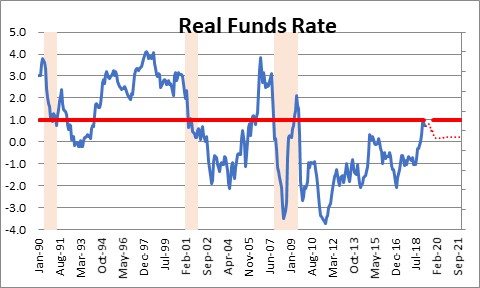

No one knows exactly what constitutes a “neutral” funds rate. For years the Fed believed it was about 3.0% because over the past 50 years, through numerous Fed tightening and easing cycles, the funds rate averaged 1.0% higher than the inflation rate. For its policy to be “neutral” the Fed believed it should put the funds rate 1.0% above its 2.0% inflation target, or 3.0%.

But more recently estimates of the “neutral” rate have been falling. In the last 30 years the “real” funds rate has averaged 0.5%, which could mean that for Fed policy to be “neutral” it should put the funds rate 0.5% above its 2.0% inflation target, or 2.5%. The Fed currently believes the neutral rate is in a range from 2.5-3.0% with median estimate of 2.8%.

But consider the following. At the end of 2021 the Fed expects the funds rate to be 2.6%. This means that for the next 2-3/4 years the funds will remain below its estimated neutral level of 2.8%. We have said many times in the past and will say once again — the U.S. economy has never, ever, gone into recession until such time as the funds rate has risen well above its neutral level. The Fed’s action this past Wednesday lowered the trajectory of the funds rate by 0.5% for the next three years, and during that period of time it may never rise to its neutral level. If previously one danger for the U.S. economy was that the Fed might tighten too much and put the economy in a tailspin, that fear is now completely off the table. As we see it, the economy has clear sailing for years to come.

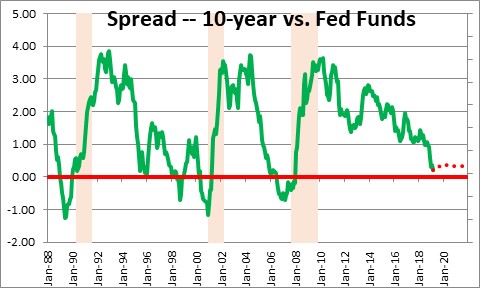

But what about the yield curve? It has flattened considerably and could be in danger of “inverting” with short rates becoming higher than long rates. An inverted yield curve is, in fact, a good harbinger of recession. With the yield on the 10-year note currently at 2.55% and the funds rate at 2.4%, the yield curve has a positive slope of just 0.15%. It is close to inverting. But in the past three business cycles the curve inverted by 0.7-1.0%. Today it still has a positive slope of 0.15%. That is a long way above the levels of inversion that occurred prior to the previous three business cycles. Furthermore, once inverted a recession did not occur for at least another year. So do not fret about the flatness of the yield curve. It is not flashing a warning signal. If the economy grows as quickly as we expect for the balance of this year and inflation edges upwards, our sense is that the yield curve will steepen somewhat to perhaps 0.3% by yearend.

Some have suggested that by taking two rate hikes off the table the Fed sees a substantial growth slowdown or perhaps even a recession next year. Rubbish. The Fed still envisions 2.1% GDP growth this year, 1.9% in 2020, and 1.8% in 2021. It also believes potential GDP growth is 1.8%. Thus, the Fed sees healthy growth for as far as it can see. We agree. Our forecast is for even more robust growth. Rest easy. All is well.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me