July 19, 2013

Inflation you might ask? What inflation? Indeed, that is the point. The inflation measure most closely watched by the Fed is expanding at about one-half the desired 2.0% inflation rate that the Fed seeks. Depending upon the economic situation at yearend, the Fed could use slow inflation as a reason to postpone reducing their monthly bond purchases.

There are a variety of inflation measures in this country. Each has positives and negatives. Let’s talk about two– the consumer price index (CPI) and the gross domestic product (GDP) deflator. The personal consumption expenditures (PCE) deflator (a third measure) is a subset of the GDP deflator. Our preference is for the CPI. The Fed gives greatest weight to the PCE deflator.

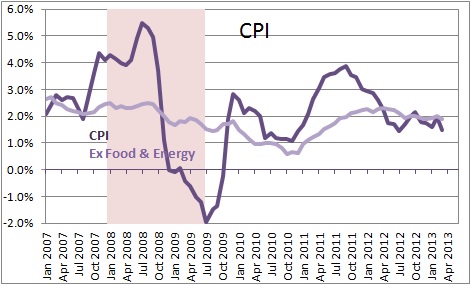

The consumer price index is, by far, the most closely watched measure of inflation. It is published monthly and reflects prices for a fixed basket of goods — food, clothing, shelter, fuels, transportation fares, doctors’ and dentists fees, and prescription drugs — that people buy for everyday living. Indeed, the CPI includes 364 different products. The advantage of the CPI is that the basket of goods is the same each month. Hence, monthly changes reflect pure changes in prices. If one is trying to answer the question, how fast are prices rising in the U.S.—i.e., what is the inflation rate — this measure seems to be the most appropriate. As always, economists love to exclude food and energy prices. Not because they do not matter, but because they are so volatile. If gasoline prices rise 6.0% one month only to fall just as quickly the following month, that has no significance and merely distorts the inflation outlook.

Currently, the CPI is climbing at a 1.8% pace overall and at a 1.6% pace excluding the volatile food and energy components. Because the Fed wants to see inflation rise at a 2.0% pace these figures are not too far off the mark, particularly if the economy is gathering some momentum.

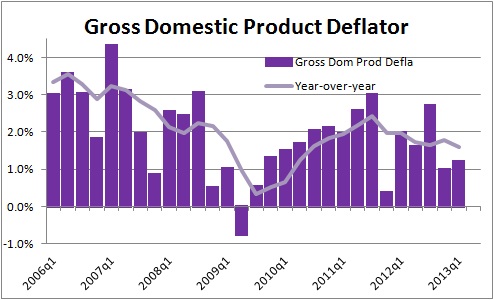

The gross domestic product deflator is a part of the GDP report. It includes more than 5,000 goods and services so the GDP deflator is, by far, the most comprehensive measure of inflation. So why isn’t it our inflation benchmark? Because it is not a pure measure of inflation. Rather it measures a combination of price changes and changes in the composition of GDP. If prices are absolutely unchanged from one quarter to the next, but GDP is comprised of more high-priced goods, the GDP deflator will increase. The classic textbook example is butter versus margarine. If consumers suddenly feel wealthier and start buying more butter and less margarine, the GDP deflator will increase. If a home builder substitutes relatively inexpensive plastic pipe for more costly copper tubing the GDP deflator will decline. Thus, the GDP deflator tells us something about price changes in a given time period, but it also provides information about how consumers and firms respond to inflation by changing spending patterns. Certainly that information is useful, but it is important to recognize that the GDP deflator is not a pure measure of inflation.

Currently, the GDP deflator is climbing at a 1.6% pace, not appreciably different from the 1.8% growth rate registered by the CPI and, once again, not too far below the Fed’s 2.0% target for inflation.

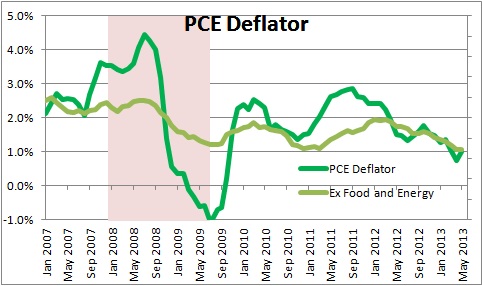

The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation is the personal consumption expenditures deflator (PCE deflator), in particular the PCE deflator excluding the volatile food and energy components. Because the PCE deflator is a subset of the GDP deflator it has all the same properties. It is not a pure measure of inflation. It measures prices for a much larger group of goods and services than the CPI which is good, but it also is a weighted measure and thereby tells us something about how consumers and businesses are responding to inflation. If one is trying to determine the inflation rate – i.e., the change in prices between one month and the next – this series does not provide the answer.

Because the Fed has told us that the PCE deflator is its preferred measure of inflation, we need to keep an eye on it. Right now the PCE deflator is rising at a 1.0% pace, and the PCE deflator excluding food and energy is growing at a 1.1% rate. Both of those figures are about one-half of the desired pace.

If GDP growth at the end of year has not accelerated to the extent that the Fed expects, it may well use the slow rate of expansion in this inflation measure as a reason to postpone reducing its bond purchases. Indeed, some Fed officials make that argument right now and actually want to accelerate the Fed’s pace of bond buying. They are still very much in the minority, but they are there and they are vocal.

The point of all this is that there are a variety of inflation measures, all of which provide some information. And while the Fed may talk about the PCE deflator and indicate that it is its preferred measure, the reality is that it looks at all inflation indicators and collectively forms a judgment about what is happening to inflation. Right now inflation is not the hot topic, but be assured that at some point in the not-too-far-distant future it will become important because it is either growing too rapidly or, perhaps, expanding too slowly.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me