March 18, 2016

At the March FOMC meeting the Fed left the funds rate unchanged at 0.25% and indicated that it would raise the funds rate two (or perhaps three) more times this year to 0.9% by yearend. In December they expected the yearend funds rate to be 1.4%. Thus, the Fed took two rate hikes out of its forecast. It was worried that the volatility in financial market conditions earlier this year might negatively impact already tenuous GDP growth in Europe and Asia. Even though economic activity in the U.S. is holding up reasonably well it chose to proceed cautiously.

We do not have a problem with the Fed’s GDP forecast. It expects 2.2% GDP growth this year; we are at 2.4%. Those two forecasts are essentially the same. Similarly, the Fed expects the unemployment rate to be 4.7% at yearend; we peg it at 4.6%.

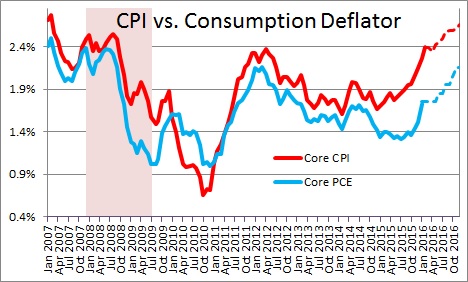

But we do have a different view with respect to inflation. The Fed targets the personal consumption expenditures deflator (excluding food and energy prices) at 2.0%. It expects that rate to rise 1.6% in 2016. We expect it to increase 2.1% – a full 0.5% faster than what the Fed expects. In that case, the rate cuts taken out of the forecast in March may resurface as the year progresses.

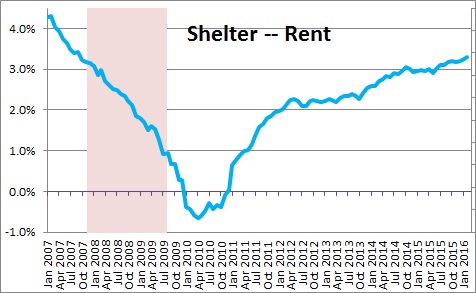

While the Fed targets the PCE deflator, the emerging inflation problem is best understood by talking about the more familiar consumer price index. The core CPI surprised on the high side in both January and February increasing 0.3% each month. The gains were widespread — shelter, medical costs, airfares, new cars, alcoholic beverages, and auto insurance all contributed to the unanticipated run-up. The increase in shelter is a big deal. It has been steadily accelerating, is currently 3.3%, and accounts for one-third of the entire CPI.

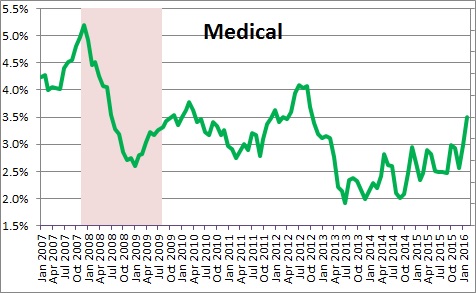

Medical costs are another problem. They have also been rising by about 3.0% but are threatening to go higher. They account for another 8.5% of the index.

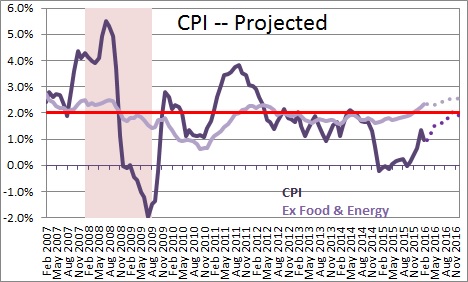

With 0.3% increases in the core CPI in January and February and 0.2% increases in each of the next ten months, the core CPI will rise 2.6% this year. But the Fed targets the core PCE deflator. It tends to average about 0.5% less than the core CPI. Thus, the core PCE seems likely to increase 2.1% in 2016. The Fed currently expects it to rise 1.6%. Maybe it is right, but we have been worried for some time that inflationary pressures are increasing but not yet obvious because declining oil prices have masked the problem.

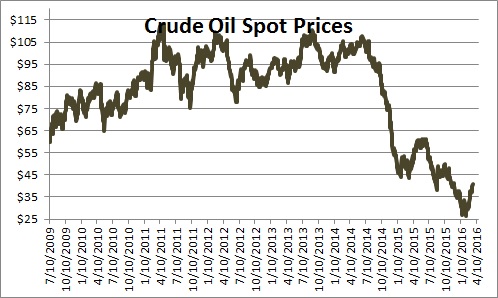

But oil prices are no longer falling. In fact, they have climbed from a low of about $26 per barrel in mid-February to $41 per barrel by mid-March. Gasoline prices have climbed 14% from $1.72 to $1.96 and are poised to go higher.

Those higher oil prices could cause the overall CPI to increase 0.4-0.5% in March and April and boost the year-over-year increase to 1.5%. The core CPI has risen 2.3% in the past year and is likely to edge its way higher as well. Suddenly, inflation will be back in the spotlight. For Fed policy makers that is a serious concern. They have been able to ignore inflationary pressures when the CPI was bumping along at 0%. A quick pickup to 1.5% is fundamentally different.

In the world of economics nothing happens gradually. When the Fed is tightening it is trying to engineer a soft landing. But typically it continues to raise rates until at some point we finally notice that interest rates are noticeably higher, we cut back on spending, and the economy slips into recession. The same thing is true with inflation. When it finally begins to climb it accelerates quickly and the Fed is forced to play catch-up. That is when the problems occur. The economy is sensitive not only to the level of interest rates but also to their trajectory. A rapid increase in rates is typically the precursor of a problem. The Fed does not want to go there.

It is time to focus on inflation. If we are right, the comforting words from the Fed in March will be less friendly as the year progresses. Stay tuned.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me