August 31, 2018

The economy is on a roll. GDP surged 4.2% in the second quarter. The stock market is at a record high level. The bull market has lasted longer than any other in history. Yet most economists do not expect the economy to sustain this pace for long. They believe that an aging population and meager gains in productivity are likely to hold back growth in coming years. They cling to the notion that potential GDP growth will remain at 1.8%. We think they have it wrong.

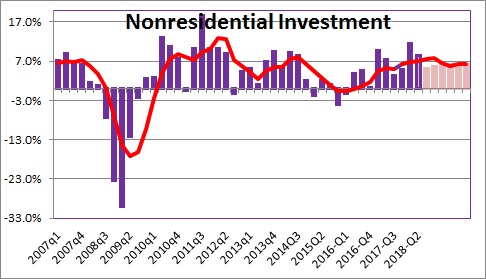

The difference between their view and ours centers upon the outlook for investment spending. After failing to grow for almost two years, investment spending suddenly took off immediately after President Trump was elected. The upswing was triggered initially by the prospect of a cut in the corporate tax rate, and it got further support when the tax cut passed Congress in December of last year. Investment spending grew rapidly every quarter in 2017 and registered 6.3% growth for the year. It is off to a fast start in 2018 with growth rates of 11.5% and 8.5% in the first two quarters of the year. As a result, we expect investment spending to register 7.7% growth for 2018 and continue at a 6.3% rate in 2019. With the labor market extremely tight and both skilled and unskilled workers in short supply, business leaders will have to spend more money on the latest technology to boost worker productivity and thereby step up the pace of production. There is no end in sight to this process.

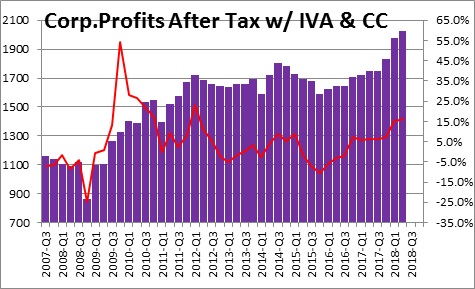

Corporations have no shortage of funds for investment spending if they choose to do so. In the past four quarters after-tax corporate earnings rose 16.1% which is the fastest growth rate since early 2012.

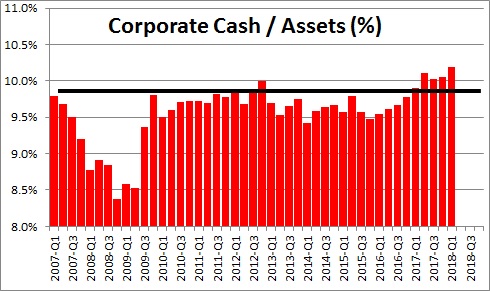

Corporate cash holdings as a percent of total assets at 10.2% are well above average and just waiting to be deployed.

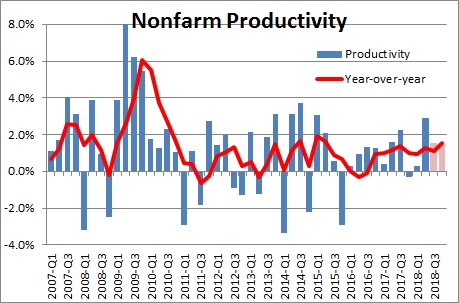

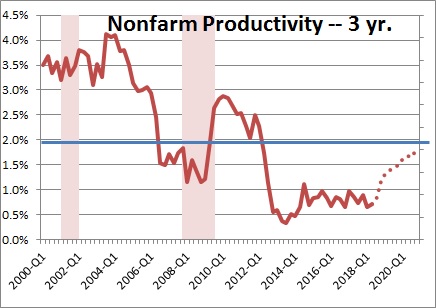

If corporations continue to invest there is little doubt that productivity growth will follow. Indeed, it has already begun to do so. After registering essentially no growth for a while, productivity grew 1.0% in both 2016 and 2017. In the first half of this year the growth rate has picked up to 1.3%. Something different seems to be happening and it is not a surprising result. When business leaders open their wallets and begin to invest, productivity growth accelerates.

Potential GDP growth is a long-run concept and, thus far, we have only talked about short-term changes. A 3-year moving average growth rate of productivity might be a better way to measure its “long-run” growth. That growth rate is still languishing at 0.7% — about where it has been for the past several years. But with faster growth in productivity in 2016, 2017, and the first half of this year and our expectation for sustained growth in the second half, we estimate that the three-year growth rate will climb to 1.3% by the end of this year and 1.5% by the end of next year. Tightness in the labor market will force business types to sock some money into technology to boost output not just this year but every year going forward. As the 3-year growth rate climbs other economists may finally acknowledge that the economy’s potential growth rate has accelerated.

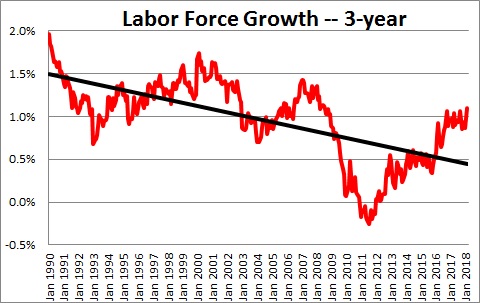

The other part of the potential growth rate equation is growth in the labor force. A couple of years ago the 3-year growth rate in the labor force was 0.8%. Because the unemployment rate has fallen to an 18-year low of 3.9%, some workers who had long since given up looking for a job are now beginning to seek employment. That means they are back in the labor force. As a result, the 3-year growth rate has climbed to 1.1%.

So, let’s re-do the potential GDP growth rate math. A couple of years ago the labor force was growing by 0.8%. Productivity was climbing by 1.0%. Add those two numbers together and potential growth – our economic speed limit – was 1.8%. Most economists believe that it is still at 1.8%. We think they are wrong.

As noted above, 3-year growth in the labor force has climbed to 1.1%. The 3-year growth rate for productivity should reach 1.2% by the end of this year. This suggests that potential growth has already climbed to 2.3%. If productivity growth continues to climb – as we expect — it is easy to envision potential growth of 2.8% by 2020.

If potential growth picks up lots of good things happen. The economy will be able to grow at a sustained rate of 2.8% rather than 1.8% without generating inflation. Faster growth in the economy will boost the rate of growth for corporate earnings. That will push the stock market higher. Our standard of living will grow more quickly. And growth in wages associated with the tight labor market will not result in rising inflation because the increase in wages should be largely offset by gains in productivity. In other words, workers will have earned their fatter paychecks by producing more goods.

We continue to wonder how long it will take for others to share our view.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me