October 6, 2023

With a surprisingly large 336 thousand increase in payroll employment for September, one can make a plausible case that the Fed will boost the funds rate by 0.25% to 5.75% at the end of this month. We disagree. We are looking for no change in the funds rate at this meeting. First, it is important to keep in mind that the entire spectrum of interest rates has risen by about one full percentage point in the past three months. That alone should slow the economy to some extent in the months ahead. Second, there is the United Auto Workers strike which, given the unprecedented demands by the union and President Biden throwing his support behind the union, suggest strongly that the strike will not end any time soon. Third, after a three-year hiatus student loan borrowers will resume payments to the government beginning this month. And fourth, the Congress is in disarray. With the ouster of House Speaker McCarthy the House of Representatives is paralyzed with a November 17 date looming on the horizon for a possible government shutdown. It is hard to imagine any significant budget progress between now and then. To be sure, third quarter GDP growth will be robust. We estimate a growth rate of 3.5% and others are anticipating something even bigger. But fourth quarter growth is poised to slow to 1.5% at best. If some of these issues are not resolved quickly it could quickly ratchet downwards to no growth or even a decline. Against this background, we suggest that the Fed will leave the funds rate unchanged at 5.5% and wait until some of these issues are resolved before deciding whether additional rate hikes might be needed.

While the level of interest rates across the board has risen sharply in the past several months, the run-up in the yield on the important 10-year note is particularly noteworthy. The yield on the 10-year was 3.46% back in April. It is currently 4.8%, which is the highest since 2007. That will clearly take a bite out of growth in the months ahead. It has led several economists to renew their call that the economy will soon fall into recession. Not so fast!

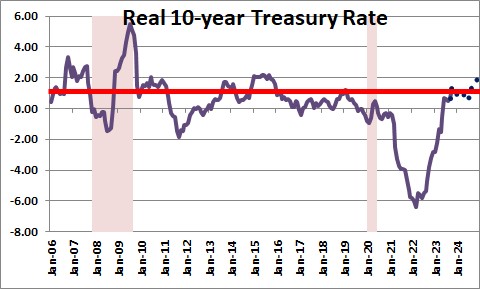

While the nominal level of the 10-year is eye-popping, the real rate on the 10-year does not appear as threatening. It has also risen, but with the 10-year note at 4.8% and the core CPI at 4.1%, the real 10-year rate is 0.7% which is roughly in line with its average for the 10-year period just preceding the pandemic. We do not believe that the current nominal yield on the 10-year will endanger the expansion.

The auto workers union is making (in our opinion) some outrageous demands. They are asking for a 40% increase in wages over a 4-year period, a 20% reduction in the workweek from 40.0 to 32.0 hours, and a guarantee of some sort of job security during the transition to the production of all-electric vehicles. Then, President Biden shows up on the picket lines and throws his full support behind the union and its demands. That poisoned any good-faith negotiations between the UAW and the automobile manufacturers because union workers will now believe that their proposals might actually be attainable. Anything less might be deemed unacceptable to rank and file union members. The auto manufacturers will probably feel that they are no longer bargaining in good faith because one side has the support of the president. Against this background, it is inconceivable to us that the strike can be settled quickly. As it progresses, the inventory of unsold vehicles will dwindle while sales and revenues slip. The negative impact on the economy will soon be apparent.

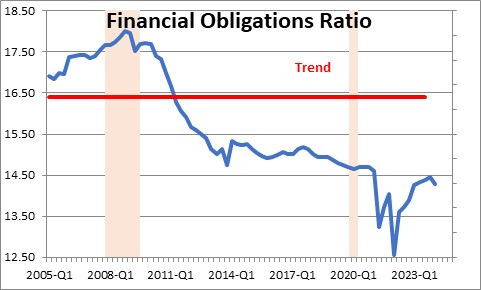

Student loans borrowers are faced with a resumption of payments on their student loans beginning this month. For the past three years student loan borrowers could use the $200-300 per month that they previously sent off to the government to spend on whatever they chose. But now that $200-300 will once again be diverted to the government. This will make it more difficult for this group of borrowers to maintain their pace of spending. They may choose to borrow against their credit cards for a while because debt in relation to income remains low, but this is clearly not a sustainable situation.

Finally, the House of Representatives is in disarray following the unprecedented ouster of Speaker Kevin McCarthy. House Republicans do not seem even remotely close to coalescing their support behind any new speaker. Who in their right mind would want the job? This is a big deal because on November 17, barring any significant progress on the budget front, the government will be forced to close. The issue is not so much the direct economic impact on GDP growth from a government shutdown, it is the perception that our leaders on Capitol Hill are paralyzed and incapable of governing. That scares the American people, is frightening to our Allies, and is a welcome opportunity for our enemies to create some mischief.

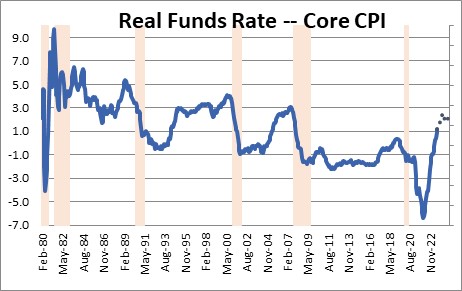

Through September the economy remains solid, but there are formidable headwinds in the months ahead. Currently with the funds rate at 5.5% and the core CPI at 4.1% the real funds rate is 1.4%. That seems to be roughly in line with the level that in the past has significantly slowed the U.S. economy. The Fed may well have to raise the funds rate further in the months ahead but, if inflation continues to shrink slowly, the peak in rates is not far distant. The Fed can resume its fine-tuning operation later if the need arises. It does not have far to go.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Steve –

You are sanguine about rates starting to come down in the not too distant future,

but John Authers this week in Bloomberg raised the likely possibility that long Treasury rates are rising because demand for long Treasuries by foreign governments, who buy 60% of them, is decreasing because of the large debts and rising deficits of the US, as well as the obvious disarray and chaos in the House which makes solutions to the first two problems impossible. If true, these conditions look likely to continue indefinitely, therefore continuing to propel rates upward if the gap between demand and supply for long Treasuries continues to increase. What do you think about this possibility?

Frank

Hi Frank,

I will send you a chart via e-mail re: foreign holdings of bills, notes and bonds. Foreign holdings of notes and bonds peaked in July 2021 at $4.0 trillion. They fell steadily through October 2022 to $3.4 trillion. Between then and July 2023 (the most recent data available) they rose slightly to $3.5 trillion. Could something very different have happened in August and September? Maybe. But I doubt it.

His second point makes more sense to me. That is, steadily rising deficits and debt outstanding combined with a completely dysfunctional Congress is the more likely problem. Whatever is going on, it seems to have happened in the past three or four months.

Does that make sense?