June 2, 2023

The monthly employment report is always a key indicator for economists in assessing the degree of economic activity for any given month. It is significant because it is the first solid evidence of what the economy did in the prior month. It has the potential to significantly alter one’s views about both the current and future pace of economic activity. If economists know how many people are working and how long they worked, they can estimate how many goods and services were produced in that month. Add to that information on hourly earnings and they can figure out the increase in income. Not only do we get the change in employment, hours, and earnings for the economy as a whole, the Bureau of Labor Statistics also provides that same information for a wide variety of industries. But every now and then the data can be confusing and nowhere is that degree of confusion more apparent than in the employment report for May. Payroll employment jumped 339 thousand in that month but an alternative measure of employment declined 310 thousand. How can this be? Did employment rise or fall? Did the economy maintain or lose momentum? How will this affect the Fed’s interest rate decision later this month?

The employment report for any given month is by far the most widely anticipated economic report. It is released on the first Friday of each month for the previous month so it provides a timely look at economic activity. We learn about employment, hours worked, and hourly earnings not only for the overall economy but every industry. If we know how many people were working and how long they worked we can make a reasonable estimate of what GDP did in that particular month. That same information for the manufacturing sector can provide a guesstimate of industrial production. Ditto for housing starts. To all of that add data on hourly earnings and out pops a good sense of what happened to personal income in that month. If an economist can have just one piece of information for any month, the employment report will undoubtedly be at the top of the list.

But sometimes the information in the report can be confusing. For example, payroll employment surged by 339 thousand in May. But civilian employment, which is the employment measure used in calculating the unemployment rate, declined 310 thousand in May. How can this be? Which one are we supposed to believe?

It is important to understand that the two estimates are derived from separate data streams. Payroll employment is calculated from data reported by a large number of employers across all industries. Employment for the unemployment rate calculation is derived from knocking on doors and asking people if they have a job. It is known as the household survey. It tends to be more volatile than payroll employment and is generally regarded as less accurate. That is because some citizens may not answer questions about their employment status truthfully when a government official shows up at their door. One conceptual difference is that the household survey includes people who are self-employed which would not be captured in the establishment survey. There is always monthly noise between the two series but over time the two surveys seem to show roughly comparable gains in employment.

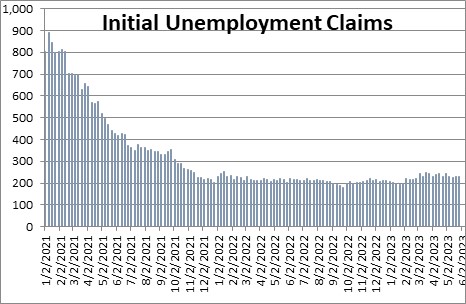

But up 339 thousand or a decline of 310 thousand? Which to choose? Go with the payroll employment gain of 339 thousand. Why? There are a variety of reasons. Initial unemployment claims – a weekly measure of layoffs – has been steady and suggests no softening of the labor market.

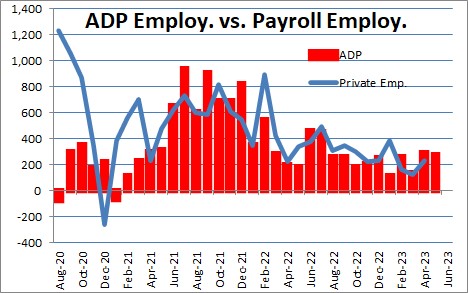

The ADP report for May recorded a similar increase in employment of 278 thousand.

And, finally, job openings remain elevated. The demand for labor continues to far outstrip supply.

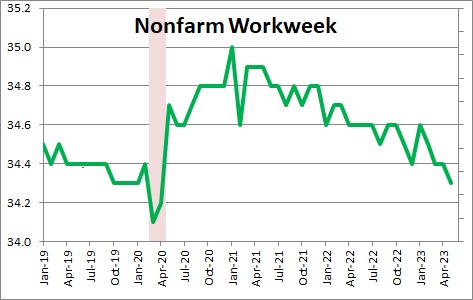

When firms are trying to boost production they have a choice of hiring additional workers or working existing employees longer hours. For more than a year firms have been eagerly hiring new workers but, at the same time, gradually shortening the workweek for existing workers. This seems to make no sense. Typically, when the pace of economic activity slows firms will initially shorten hours rather than lay off workers because they have no idea whether the slowdown will be temporary or much longer lasting. If the drop-off in demand continues, firms will eventually be forced to lay off workers. But that has not been the case recently. The workweek has been falling for a year, but hiring continues apace.

The consensus view is that the economy will slip into a mild, short recession in the final two quarters of this year. If that is the case, firms might need to hire or re-hire workers early next year. For now they have chosen to shorten hours but keep hiring as many qualified workers as they can. If the economy keeps chugging along slowly, at some point firms will recognize that they have more than enough workers to satisfy demand for the foreseeable future and the layoffs will begin.

With respect to the Fed, the employment data are sufficiently confusing that it will almost certainly opt to forego a rate hike in mid-June. But Fed officials still suggest that additional rate hikes may be required later in the year because core inflation remains relatively sticky.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen, I would agree that you stay with the data that you have always used in the past. To change sources mid-stream makes no sense. You could develop data from each source simultaneously, watch which one more accurately points out what is actually going on. Thank you again for your excellent analysis and thinking on the economy. I appreciate it very much.

Thanks Darrel. We continue to see data that are not behaving in exactly the same way we have seen historically. Makes it a challenge. People like me who pore over data are able to look at half a dozen indicators of something — like the labor market. But who has the time to do that? In this case, if four labor market indicators are reasonably robust and one weak, I will go with the old preponderance of evidence pointing in the strong direction.

The one argument I have heard about why civilian employment was so weak in May, is that it includes small firms where payroll employment focuses exclusively on larger firms. If because of the banking crisis the supply of credit is being cut off to those firms, then perhaps they are having to retrench on their willingness and/or ability to hire workers. That makes logical sense to me, but the ADP report breaks the overall increase in employment by size of firm, and it is precisely the smaller institutions that accounted for the big increase reported by the ADP report in May. The confusion remains. In the end, it may just be the usual monthly wiggles and statistical noise.

Steve