August 2, 2019

The consensus view is that growth outside the U.S. is crumbling which will, in turn, drastically reduce U.S. GDP growth next year. Then this past week Trump introduced more tariffs on consumer goods from China which will, presumably, exacerbate that weakness. But let’s introduce a dose of reality.

The global weakness certainly gets headlines and encourages the doomsayers. Even most Fed officials buy into the story. The fear of a global growth slowdown slipping into the U.S. was the motivating factor behind the Fed’s decision to cut the funds rate 0.25% this past week and to plan another 0.25% cut before yearend. That would put the funds rate in a range from 1.75-2.0%. The Fed insists it is buying “Insurance”. But the markets believe that the global economy is so downtrodden that the funds rate will fall to 1.25% by December 2020. That view is far too pessimistic.

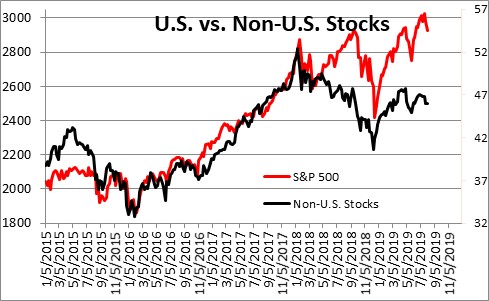

If the global economy was collapsing, wouldn’t you expect to see some hint of that weakness show up in the stock markets around the world? Global stocks hit a low in the fourth quarter of last year, rallied sharply, reached a peak for the year in mid-April, and are now just 3.5% below their high for the year. In the U.S., stock prices crumbled in the fourth quarter, quickly recovered all of those losses and hit a series of record high levels during the past couple of months. It is hard to see signs of significant global economic weakness from the behavior of stock markets anywhere.

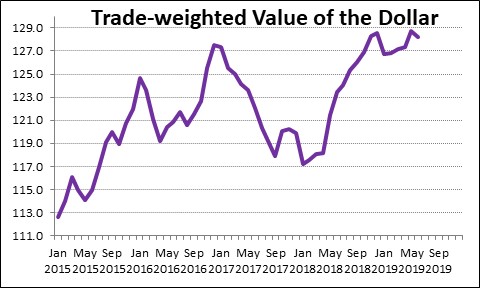

What about the dollar? Perhaps the fear of collapsing GDP growth outside the U.S. is causing global investors to pour money into the U.S. stock and bond markets. That happened last year and the dollar climbed by 8.0%. Emerging economies need raw materials to fuel their industrial-based economies. But those required raw materials are all traded in dollars. As the dollar climbs the cost of those raw materials increase. Those emerging economies become less able to compete in the global market place and economic growth slows. But the dollar stopped climbing at the end of last year. It is at the same level today as it was in December. While it was a factor contributing to slower global growth last year, its steadiness in the first seven months of this year means that it is no longer the case.

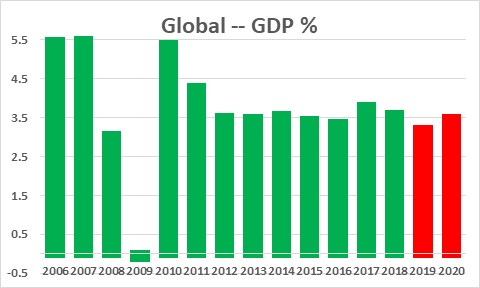

Perhaps organizations like the IMF, which tend to have a better handle on global growth than anybody else, have been so spooked that they have marked down their global growth forecasts. But they haven’t. The IMF recently cut its global growth forecasts for 2019 and 2020 by 0.1% apiece to 3.2% and 3.5%, respectively. That is not significantly different from the pace we have experienced for the past seven years.

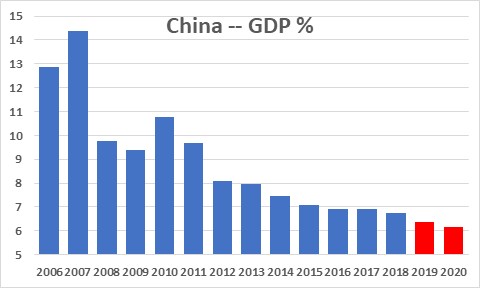

One might think the reduced global growth outlook was caused by China. But the IMF cut its China GDP forecasts by only 0.1% for 2019 and 2020 to 6.2% and 6.0%, respectively. Growth in China has been gradually slowing for almost a decade with few repercussions on the U.S. economy. The IMF made much more meaningful growth reductions for Russia, India, Latin America, the Middle East, and South Africa. Slower growth is evident everywhere. It is worth noting that the forecast for the Euro area was unchanged at 1.3% this year and 1.6% for 2020. Europe gets a lot of negative press about its economy which, while anemic this year, is expected to recover somewhat in 2020. Also of note is that the IMF forecast for the U.S. in 2019 was revised upwards by 0.3% to 2.6%.

Tariffs are not good for growth. But right now the fear of their potential impact is far worse than what the reality is likely to be. The market has been fretting about tariff issues for several years. The trade component of GDP subtracted 0.3% from GDP growth in both 2017 and 2018. In the first half of this year it had no impact on growth – it added 0.7% to growth in the first quarter but subtracted an equal amount in the second quarter. Trade matters. But keep in mind that it represents just 10% of the U.S. economy. It can alter growth in any given year by a couple tenths of a percent, but it is not going to push an otherwise healthy economy into recession.

For what it is worth we expect GDP growth this year of 2.6% and expect it to remain stable at 2.5% in 2020. Trade may well reduce growth next year by 0.2% or so which means that in the absence of trade GDP growth would be a healthy 2.7%.

Meanwhile, the core personal consumption expenditures deflator looks likely to climb from 1.6% currently to 1.9% by the end of this year and to 2.2% in 2020. Higher prices on goods from China are one reason to expect a somewhat higher inflation rate next year.

Healthy GDP growth rates of 2.6% and 2.5% this year and next combined with a gradual pickup in the inflation rate to a pace slightly above the Fed’s 2.0% target, is not a recipe for steadily falling interest rates. The Fed seems intent on another rate cut by yearend which would lower the funds rate to 1.75-2.0%. That means that the “real” or inflation adjusted funds rate would be negative which puts it squarely into an “accommodative” mode. Trump may blame the Fed for growth not reaching the 3.0% mark he has promised. But the under performance of the economy has not been caused by the Fed and rate levels that are too high. Instead, it is his trade policy which is the primary culprit. If he wants faster growth, he might try to work out trade deals with China, Canada, Mexico, and Europe.

But before we jump on Trump too hard for his trade policy, keep in mind that the objective is to get China to play by the same rules of conduct as everybody else. He wants them to stop stealing our technology and unfairly subsidizing their export industries. That is a worthwhile objective and tariffs may help make that happen. But tariffs come with a cost in the form of reduced U.S. GDP growth. He can have more vibrant growth without tariffs, or he can impose tariffs, encourage the Chinese to adopt better trade practices, but at the expense of 0.2-0.3% slower GDP growth. He cannot have both.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Hi Stephen

Thanks for your thoughtful posts. I enjoy following what you have to say.

Could I ask for your view on whether the trade tensions could have broader macro effects on confidence and on investment? Although trade makes up a small percentage of overall GDP do you think the uncertainty generated has a more substantial impact on GDP?

Regards

M

Good question. Thanks for asking. I just wrote a rather lengthy response to your question but something odd happened and it did not post. Let me do this in two parts. First, let me just post this and then come back with a more extended reply.

Clearly, confidence matters. Consumer confidence. Business confidence. If we lose the faith the economy is going over the edge. Having said that, I do not think we are at that point. As you noted, trade is a small percentage of the economy, and trade with China a small percentage of the trade component. As I noted in the article I think the ripple effect with subtract 0.2-0.3% from GDP growth. I cannot see this be the catalyst for a recession.

Investors react to all sorts of things. The latest worry is trade. But that is what investors and the stock market do. To me this feels a lot like the fourth quarter of last year when the stock market got in a tizzy about recession. They thought first quarter GDP growth could be negative. Turned out to be 3.1%. Then, the stock market turned upwards, soon recovered, and set a string of new, record high, levels. The recent selloff could translate into some sort of stock market correction but, at some point, should regain its footing. I guess we will see.

Thanks for asking. Let’s hope for the best.

Steve