March 23, 2018

Two weeks ago, President Trump announced widespread tariffs on global imports of steel and aluminum. He is currently in the process of exempting many of our closest allies and trading partners. This week he narrowed the focus and homed in on China by imposing tariffs on $60 billion of goods imported from China, much tighter restrictions on Chinese acquisitions of U.S. firms, and controls on transfers of technology to Chinese firms. Trump stated clearly that the Chinese have attained U.S. technology through intimidation, state financed acquisition, and subterfuge. It is not clear how this will turn out. The objective seems to be to force China to make concessions as it contemplates a substantial loss of exports. If they agree to concessions many of the trade restrictions could be lifted. As economists we do not support the wide-ranging set of tariffs introduced previously. We support free trade. But we also believe in fair trade and that is where the problem lies. China, and a handful of other countries, do not play by the same rules as everybody else. While perhaps not an optimal solution, Trump’s policies might ultimately produce a more level playing field– and that would be a good thing.

Macroeconomists almost unanimously support the notion of free trade. All countries can attain a wider variety of goods and services at lower prices than would occur in the absence of trade. Thus, free trade is a good thing – at long as the rules are the same for everybody.

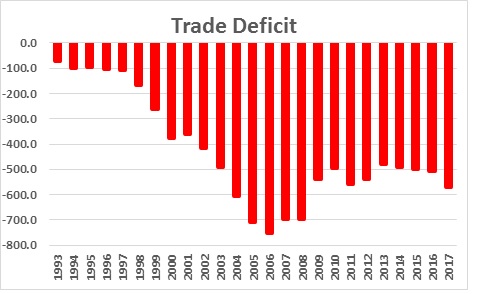

Some economists fret about the magnitude of the trade deficit. We do not. Last year the deficit was $568 billion consisting of an $811 billion deficit in goods, partially offset by a $243 billion surplus in services. But a deficit of $568 billion means that we purchased $568 billion more of foreign goods and services than they purchased from us. As a result, foreigners on balance accumulated $568 billion of U.S. dollars. What do they do with those dollars? They establish businesses in the U.S. They hire American workers. They may put the money in the U.S. stock market. We fail to see why that is such a bad thing.

Furthermore, we have had a trade deficit of roughly that magnitude since the early 2000’s and nothing bad has happened. So what is the problem? It is not the magnitude of the trade deficit that is the issue but, rather, the terms of trade with a very small number of countries.

As noted earlier, we are big believers in free trade but that trade must also be fair. That is not the case. Some countries cheat. Below is a picture of the U.S. F-35 fighter which has our most advanced technology. The other picture is the equivalent Chinese version. Can you tell the difference? We cannot, and we do not think that result is an accident.

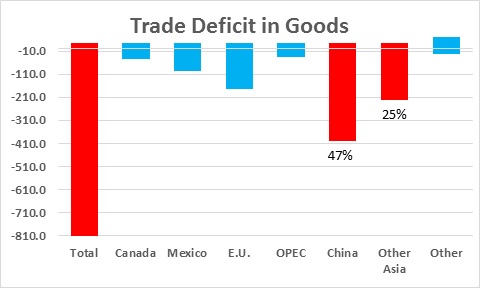

It is abundantly obvious that our trade problems exist with a very small number of countries. In fact, of the $811 trade deficit in goods last year, almost one-half of the entire amount of the deficit was with China. An additional 25% was with a small number of countries in Asia. Thus, in our view, the very broad tariffs announced previously by President Trump made no sense. We do not have a trade problem with our neighbors Canada and Mexico. We do not have a trade problem with Europe or OPEC countries. We do not have a trade problem with Australia.

We have a trade problem with China and a few other Asian countries. Hence, tariffs and other measures directed at the problem countries seem to make some sense. It would be desirable if all the countries involved sat down, had some serious discussions and, in the end, agreed to abide by the same rules. That is not going to happen. While perhaps not ideal, Trump’s imports on tariffs from China, and the other trade measures designed to restrict the flow of technology to that country, will certainly get the attention of Chinese leaders. Yes, there will be repercussions as the Chinese impose similar tariffs. Both countries will lose. The Chinese will see a reduction in their exports of goods to the United States. They will have less access to advanced technology. American consumers will experience higher prices on Chinese made goods when they shop at Amazon, Walmart or Target. In the short run both countries lose. But in the longer-term American firms may be able to compete in the global market place with a level playing field. In that environment, American firms can compete successfully with anybody.

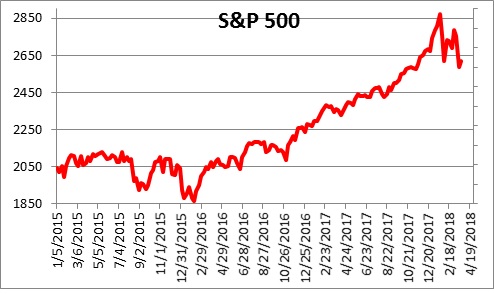

In the end, focused trade restrictions will not push the U.S. economy over the edge into recession. Trade is simply not a big enough piece of the GDP pie for that to happen. But it will put a crimp in corporate earnings which will slow the rate of growth in the stock market. And it will boost the inflation rate. Those are not positive events. But the announcement of trade measures against the Chinese is part of a negotiating process designed to bring about changes in the way the Chinese do business with the rest of the world. We will see how successful that strategy might be.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me