March 29, 2024

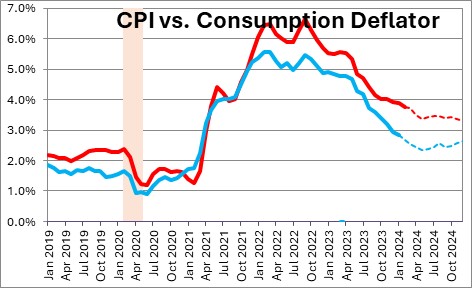

Crude oil prices have been on the rise since the beginning of the year which some economists believe could delay a midyear Fed rate cut. We disagree. While both crude oil and gasoline prices have risen, there is likely to be little spillover into the core rate of inflation for either the CPI or the personal consumption expenditures deflator — the latter of which is the specific inflation measure that the Fed targets at 2.0%. It would take a far larger increase in energy prices to derail the summer rate cut. Once underway the funds rate should drop by 3.0 percentage points over the course of three years.

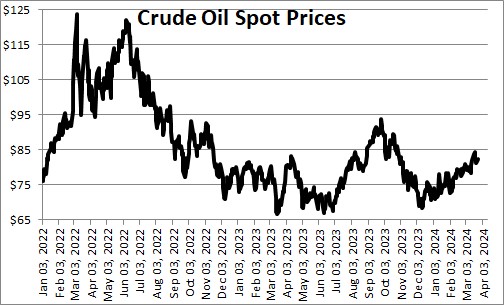

Crude oil prices have risen from $71 per barrel at the end of last year to $83 per barrel currently. That gain of nearly 20% is impressive, but it follows a sharp 22% drop in crude prices from $91 per barrel at the end of September to $71 at yearend. This is exactly why economists like to exclude food and energy prices from their analysis of the underlying rate of inflation. Those two commodities are particularly volatile and including them can make it difficult to assess changes in the trend rate of inflation.

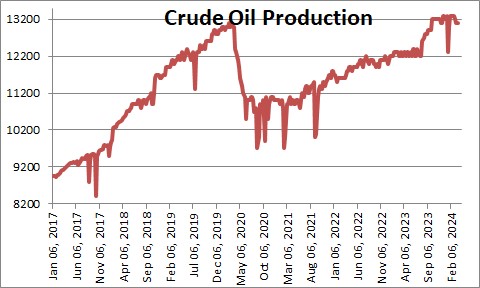

For what it is worth, the big drop in crude prices late last year was triggered by a dramatic increase in production from 12.2 million barrels per day at the end of July to 13.2 million barrels per day by early October. However, the Energy Information Agency expects no further increase in production between now and the end of 2024 and, as a result, it anticipates a rebound in crude prices to $88 per barrel by yearend versus the current price of $83 Such a further increase should not be troublesome.

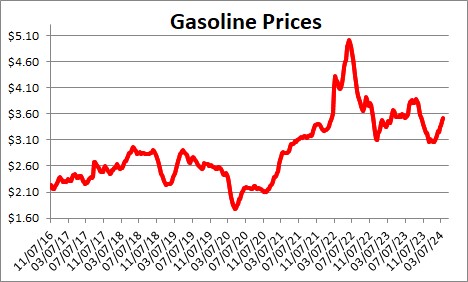

Perhaps more relevant to consumer prices is the price of gasoline. Its behavior has mirrored that of crude prices, but to a lesser extent. At the end of September gasoline was $3.84 per gallon. It fell to $3.11 by the end of the year, and is today at $3.52. Importantly, the EIA expects gas prices to be $3.48 at the end of 2024. If that is correct, gasoline prices should have a negligible impact on either the CPI or the PCE inflation measures for the year.

We continue to expect the core CPI to shrink from 3.8% today to 3.4% at year end. We anticipate the targeted core PCE deflator to be steady at 2.8% through December.

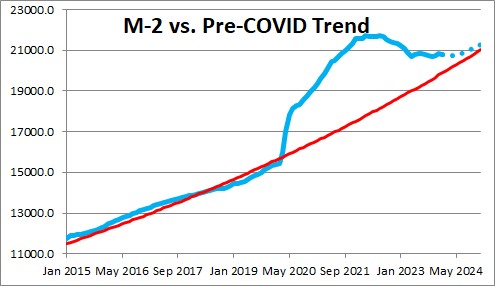

Our belief in a further slowdown in inflation is based to a large extent on the Fed continuing to shrink its balance sheet for several more months thereby eliminating all of the surplus liquidity it created between the spring of 2020 and March 2022 when it purchased literally trillions of dollars of U.S. Treasury and mortgage-backed securities. When the Fed finally stopped purchasing securities in March 2022 the economy was awash in $4.0 trillion of surplus liquidity. That surplus liquidity was the root cause of the explosion in inflation. That amount has shrunk to $0.8 trillion currently, and if the Fed continues to shrink its portfolio it should be eliminated by midyear. As the amount of liquidity in the economy once again approaches the amount that the economy actually needs, the inflation rate should continue to slow gradually.

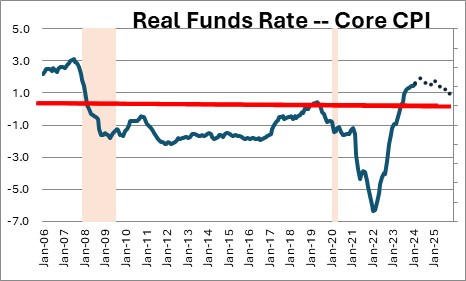

If that inflation outlook is accurate the Fed should soon begin to cut the funds rate. Currently, the funds rate is 5.5%, the core CPI is 3.8%, hence the “real” funds rate is the difference between those two numbers or +1.7%. The Fed believes that when the economy is in equilibrium – i.e., the unemployment rate is around the 4.0% mark at which level everybody who wants a job has one, GDP growth is roughly in line with its long-run potential growth rate (currently estimated to be about 2.0%), and inflation is steady at the desired 2.0% pace, the funds rate should be 2.5%. Given that inflation in that world is 2.0%, then the so-called equilibrium “real” funds rate should be +0.5%. The current “real” funds rate is +1.7%. Fed policy is in restrictive mode as it should be with the core CPI still far too high at 3.8%. However, it seems appropriate for the Fed to gradually lower the “real” rate with the goal of it returning to the long-term equilibrium level of +0.5% by 2026. With the unemployment rate very low at 3.9%, the economy chugging along at roughly a 2.2% pace, and inflation continuing to shrink gradually, the Fed can begin the easing process, but it does not have to be in any great rush.

Like most everybody else we expect three rate cuts this year which would lower the funds rate to 4.75% by yearend. The core CPI should slip to 3.3%. Thus, the “real” funds rate at yearend would be +1.5% — little different from the +1.7% real funds rate currently. The pace of Fed easing should be only slightly faster than the slowdown in inflation. If all goes well the core CPI should slow further to 2.6% by the end of 2025. We expect the Fed to reduce the funds rate further to 3.5% by the end of that year. Thus, the “real” funds rate should drop to +0.9% by the end of 2025.

The point of all this is that the recent run-up in energy prices should have little impact on Fed policy for the balance of this year, and the Fed should initiate an extended easing cycle by summer with the funds rate falling by 3.0 percentage points over the course of three years.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Thank you stebe