October 20, 2023

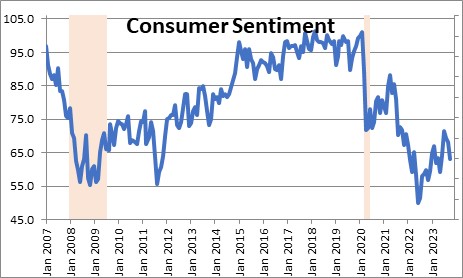

Consumer sentiment today is far below the pandemic-induced recession level of 2020 and roughly where it was at the low-point of the 2008-09 so-called great recession – the longest and deepest recession since the depression in the 1930’s. One wonders why consumers are so discouraged. The answer seems to be that prices have risen sharply in the past four years and paychecks have not kept pace. The Fed intends to slow the rate of inflation to the 2.0% mark but that means that the rate of increase in prices will slow from a peak of 9.0% a year ago to 2.0%. The Fed has no intention of reducing prices to a more affordable level. Real weekly earnings — worker paychecks adjusted for inflation — are essentially the same size today as they were four years ago and workers have noticed. No wonder there has been so much increased union activity in the past year.

Consumer sentiment typically drops sharply during a recession. But in this case sentiment has plunged in the absence of a recession. That does not happen. What is going on? The answer seems to be that prices have risen dramatically in the past four years. Worker paychecks have not grown commensurately.

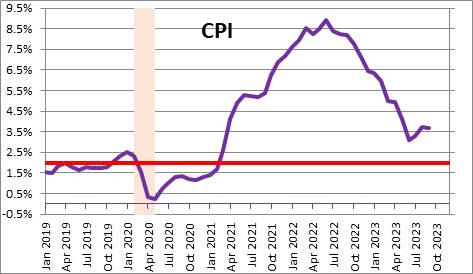

Typically,the Fed looks at the year-over-year increase in the CPI. It has slowed from 9.0% in June 2022 to 3.7% currently. The Fed’s inflation target is 2.0%. The Fed is thrilled that inflation has peaked and is headed in the right direction. The average consumer is far less thrilled. The problem is that what the Fed is looking at is very different from what consumers see.

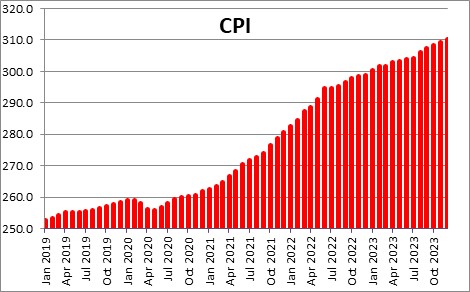

Consumers are looking at a sharp increase in prices from 2020 through 2022. The Fed believes the pickup in inflation was “temporary”. In Fedspeak that is true. The rate of increase in prices (inflation) has slowed from 9.0% a year ago to 3.7% and appears to be headed lower. But consumers find that the price of virtually everything they buy has risen dramatically and is showing no sign of coming back down.

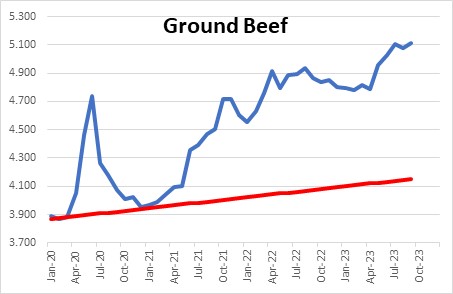

For example, ground beef cost $3.87 just prior to the recession. Today it stands at $5.11. That is an increase of 32% in less than four years. The charts for every food category are virtually identical. The price for boneless chicken breasts has climbed from $3.05 per pound to $4.23 – an increase of 39%. The price of a gallon of whole milk has risen from $3.25 to $3.96 – an increase of 22%. A dozen eggs has risen from $1.46 to $2.07, an increase of 42%. Pork is up from $3.37 to $4.33, a gain of 28%.

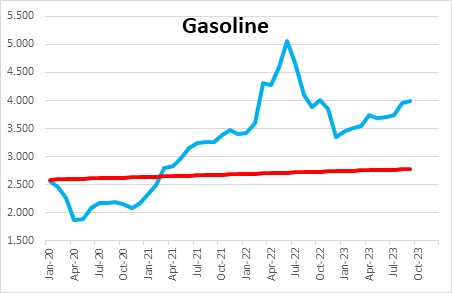

Gasoline has risen from $2.56 to $4.00 – an increase of 56%.

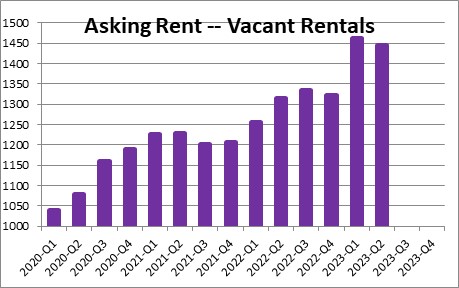

Rent? Same problem. The asking rate for vacant rentals has risen from $1,041 to $1,445 – a jump of 38%.

Consumers have to eat, pay the rent, and they fill the car with gas to get to work. These price increases are hard to escape and have hit workers at the low end of the income scale who spend almost all of their paycheck on these necessities the hardest. No wonder consumer sentiment is so low!

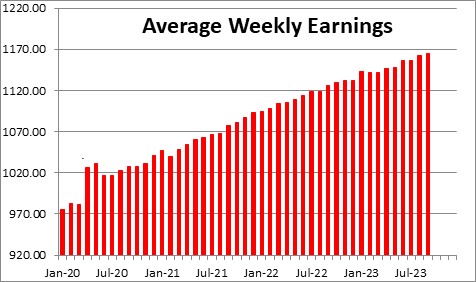

Worker paychecks have not kept pace with the increase in prices. In nominal terms average weekly earnings have risen from $975 to $1,165 a gain of 19% or about 4.5% per year.

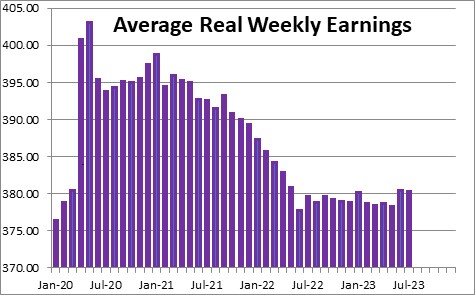

Adjusted for inflation, real weekly earnings have risen from $376.45 to $380.25, a measly total of 1.0% in the past four years. Inflation has completely countered the nominal increase in wages. Workers are no better off today than they were four years ago.

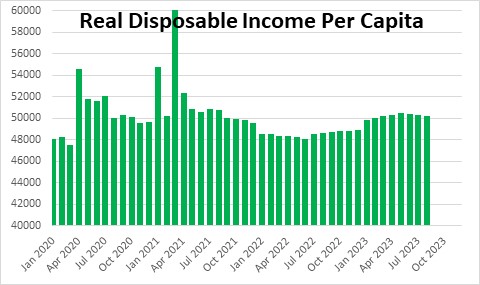

Perhaps the best way to summarize all this is to look at real disposable income per capita. That measure starts with personal income which includes wages and proprietors’ income as well as transfer payments from the government (like Social Security, Medicare, and those stimulus checks sent out in 2020 and early 2021). It subtracts taxes and adjusts for inflation and population growth. It essentially measures changes in an individuals’ purchasing power. It is often used as a gauge for growth in our standard of living. It was $47,829 prior to the recession. It stands at $49,951 as of August. That is an increase of 4.4% over almost four years or about 1.0% per year. The government helped to boost income in 2020 and 2021, but there are no more stimulus checks in sight.

In real terms worker paychecks and income are no bigger today than they were four years ago. Consumers have noticed. This is why there has been so much increased union actively since the beginning of this year from railroad workers, airline pilots, screenwriters and actors, auto workers, UPS employees, and health care workers. Even baristas. Union leaders are trying to claw back some of this lost income for their members.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

The numbers you present are surprising, but undeniable. I haven’t seen anyone

else among popular media economics writers summarizing the problem so succinctly and pointing out the extraordinary decrease in living standards which the average consumer has sustained. Why has this discrepancy developed? And why did average wages not rise in parallel with the cost of everything else during this inflationary surge? How does this compare to previous periods when inflation was high, such as the 70’s? The whole situation seems extraordinary, when otherwise the economy seems to be booming along. How do you see it getting corrected?

Hi Frank,

You ask good questions. I have a feeling that because it is those on the lower end of the income scale that are being hurt the worst, their voices are least likely to be heard. But, at last, the issue seems to be drawing some attention. Perhaps this widening income disparity underlies much of the divisiveness in this country. The folks at at the bottom are beginning to demand their fair share. Recent union settlements have all resulted in big wage hikes. But those will get passed along to consumers which will translate into higher prices. Inflation could begin to climb again or, perhaps more likely, its descent will be quite slow from this point on.