June 30, 2023

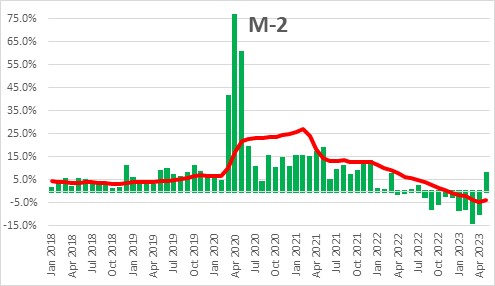

We believe that the primary cause of the run-up in inflation in 2020 and 2021 was excessive growth in the money supply. The Fed initially believed that the inflation surge was caused by temporary factors such as the dramatic increase in energy prices and supply shortages that materialized following the surprisingly robust, extremely rapid, economic rebound that occurred once the recession ended. Given that it believed that the run-up in inflation was temporary, the Fed did not tighten until two years after the inflation rate had begun to climb. Today, most economists concur that the run-up in inflation was triggered by excessive growth in the money supply between March 2020 and December 2021. But then the money supply began to decline in April 2022 and has fallen every single month since then. Now many of these same economists are suggesting that the recent contraction in the money supply means that the Fed is not providing enough liquidity to allow the economy to keep growing and, as a result, a deep recession is in store at some point down the road. We do not buy it. We suggest that the recent declines in the money supply are simply eliminating some of the excess liquidity created by its initial surge in growth in 2020 and 2021. Indeed, there is still some surplus liquidity in the economy which will provide continuing support for consumer and business spending in the months ahead and prevent the core inflation rate from declining rapidly. In our view, the proper policy prescription is to allow the money supply to continue shrinking through the end of this year.

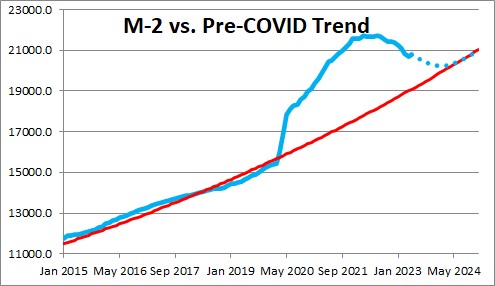

The money supply is nothing more than a measure of liquidity in the U.S. economy. Add up the cash that all of us have in our wallets, the amount in our checking accounts, savings accounts, and money market funds, and we end up with the M-2 measure of the money supply. It typically grows roughly in line with nominal GDP. In the past 20 years it has grown on average about 6.0% per year – until 2020.

When the economy shut down in March and April 2020 the Fed quickly bought $2.5 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities to prevent the economy from entering an even deeper recession. As a result, M-2 in March, April, and May 2020 grew at annualized rates of 41%, 76%, and 60%, respectively. The level of the money supply soared far beyond its historic 6.0% path. The economy was awash in surplus liquidity. But the problem got worse. Following the three-month surge in growth, M-2 kept climbing at a double-digit pace for another eleven months, eclipsing its historic 6.0% growth path. By December 2021 the economy had a staggering $4.0 trillion of surplus liquidity. Money supply growth flattened out for several months and then began to decline every month from August 2022 through April of this year.

Given that M-2 should have been growing at about a 6.0% pace, the protracted period of steady declines has caused many economists to conclude that the Fed is starving the economy by not providing it with sufficient liquidity. As a result, they fear that the economy is going to fall into a deep recession, most likely in 2024. We do not buy into that scenario.

In our view, it is the level of the money supply that is important. Suppose your liquid assets, your own personal money supply, was $100 in February 2020 – just prior to the recession. If it grew at the same rate as the aggregated M-2 measure of money, it would have reached a peak of $140 in March 2022 before shrinking to its current level of $134. If, alternatively, it had grown at its historic rate of 6.0% throughout that entire time period your personal money supply today would be $121. Do you feel like you do not have enough cash in the bank and money in your savings accounts and money funds to keep spending at a moderate pace? No! In fact, you still have about 10% more liquidity than you need, which will allow you to spend at a moderate rate from now through the end of the year.

Rather than look at the money supply on an individual basis we turn to the M-2 measure of money which is a measure of liquidity for the economy as a whole. The picture looks identical. Money growth surged, continued to grow rapidly, and then began to decline. It is currently $1.7 trillion in excess of where it would be had it grown at its historical rate of 6.0% for the past three years. The economy is not being starved of money. Rather, surplus liquidity remains, which will allow consumers and businesses to keep spending at a moderate rate for some time to come. How long that time might be depends upon what the Fed allows the money supply to do in the months ahead. If money continues to decline, that surplus liquidity will be eliminated by the end of this year. Once that happens spending should slow and the core inflation rate might begin a more rapid descent.

In remarks made this past week, Fed Chair Powell indicated that he did not expect the core inflation rate to return to its 2.0% target until 2025. It certainly does not sound like he believes the economy is being starved of liquidity.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Great analysis Steve!

Hi Barry. Nice to hear from you. Hope all is well.

Steve