April 26, 2019

There has been a lot of chatter lately about a moderate reduction in foreign holdings of U.S. Treasury securities last year. Frankly, we think this is much ado about nothing. But before exploring foreign holdings of Treasuries, who actually owns U.S. Treasury debt?

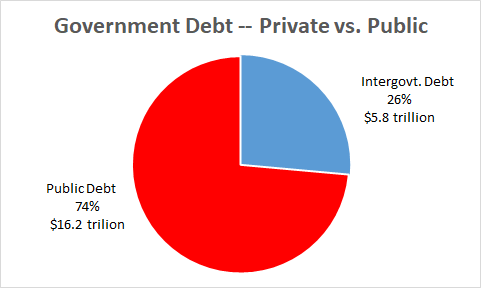

The Treasury divides outstanding debt into two broad categories – intergovernmental debt and debt held by the public. At the end of March total debt outstanding was $22.0 trillion. Of that, $5.8 trillion or 26% was held by a variety of government agencies. The remaining $16.2 trillion or 74% was held by the public.

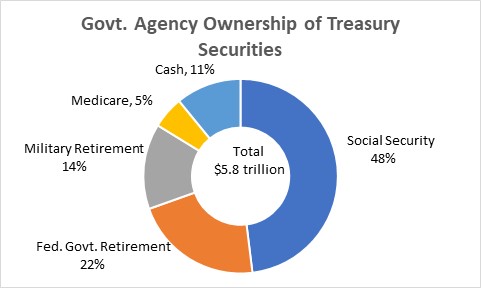

Intergovernmental Debt, $5.8 trillion. You might wonder why more than 200 government agencies own U.S. Treasury debt. The answer is that some agencies, like Social Security, collect more revenue from taxes each month than they need. Rather than let that money sit idle, the agency buys U.S. Treasury securities. Eventually these agencies will need to redeem their Treasury notes and bonds for cash. When that happens the Treasury will have to raise taxes, cut spending, or issue more debt. Which agencies own the most Treasuries? Social Security — by far — which accounts for almost one-half of the total, with Federal and military retirement funds accounting for another 36%.

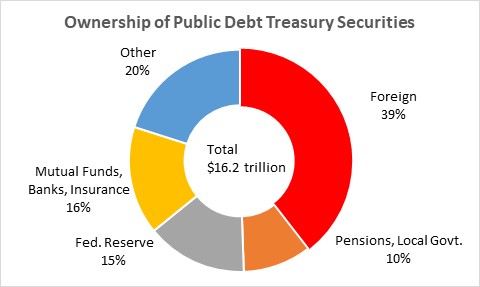

Publicly Owned Debt, $16.2 trillion. These are the Treasury securities that we typically think about. It might surprise you that $2.3 trillion or 15% of the $16.2 trillion of so-called “publicly owned” securities are owned by the Federal Reserve. The reason for that is that those securities were initially owned by somebody else, perhaps you and me. When the Fed went on its bond buying spree in the past couple of years it purchased those securities from private owners and they now reside at the Fed. Another 46% is owned by a combination of mutual funds, banks, insurance companies, pension funds and similar types of financial institutions. That means that the remaining $6.4 trillion of Treasury securities are owned by foreign institutions.

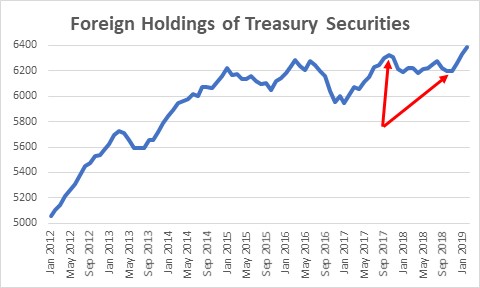

Foreign Owned Debt, $6.4 trillion. This is the portion of U.S. Treasury debt that economists tend to worry about the most. The fear is that if debt outstanding continues to climb by $1.0 trillion every year (the expected magnitude of future budget deficits), at some point foreign holders will worry about the U.S. government’s ability to service its debt which means it could ultimately default on its interest and principal obligations. As a result, foreigners could stop purchasing or possibly even sell some of their Treasury securities. Between November 2017 and November 2018 some squinty-eyed economists noted that foreign holdings declined by $100 billion from $6.3 trillion to $6.2 trillion and they sensed some heightened reluctance to hold Treasury securities. Somehow it makes no sense to us that a 1.5% decline over the course of one year should set off alarm bells.

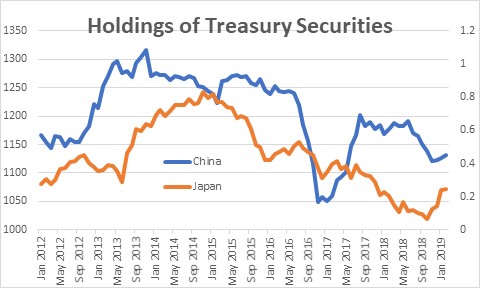

When trying to discern reasons for the 2018 drop one should look first at the holdings of China and Japan. each of which have roughly $1.1 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities and, combined, account for 35% of the total. Both countries are interested in purchasing U.S. Treasury securities because doing so boosts the value of the dollar and therefore weakens their own currency. That, in turn, keeps their exports affordable for U.S. consumers. Are these two countries likely to stop purchasing U.S. Treasury securities any time soon? Unlikely. In the November 2017 – November 2018 period total holdings of treasury’s by foreigners declined by $100 billion. China’s holdings declined $55 billion; Japan’s fell by $48. That accounts for the entire drop. Changes elsewhere were largely offsetting.

In addition to the decline in holdings by China and Japan, Russia’s holdings of Treasuries fell $93 billion from $105 billion to $13 billion in the period of time. Why these big declines? Given the timing of the decline and where it occurred, it is clear that the drop was triggered by the threat of Trump-imposed trade sanctions. In no way did the decline reflect a fear about the U.S. Treasury possibly defaulting on its debt. Political considerations were the catalyst.

Rounding out the top five holders of Treasuries are Brazil, Ireland, and the U.K. each of which holds about $300 billion. For these three countries, changes in Treasury holdings in that 12-month time period were +$46 billion for Brazil, -$45 billion for Ireland, and +$61 billion for the U.K. (presumably caused by the possibility of an ugly Brexit withdrawal). Slightly further down the list (but still in the top 10) are Luxembourg and the Cayman Islands. Both countries receive vast sums of money from global wealth and hedge funds whose owners do not want to reveal their ownership positions.

It is also worth noting that in the four months since November foreign currency holdings have surged by $184 billion and climbed to a record high level of $6.4 trillion. So much for the theory these economists were trying to develop.

As we see it, the two biggest owners of Treasury debt, China and Japan, have a big stake in buying Treasury securities to keep their own currencies undervalued and their exports cheap for U.S. consumers to purchase. They have no incentive to sell Treasuries.

Furthermore, size considerations are important. Should the Chinese, Japanese, or anybody else suddenly worry about a default by the U.S., there is no other capital market large enough to accommodate purchases of $6.0 trillion.

Finally, if countries become disenchanted with the U.S. where might they go that would be safer? The Euro? The British pound? The Chinese yuan? The Japanese yen? Bitcoin? Somehow those alternatives do not seem particularly appealing.

Given that we will soon see an uninterrupted string of $1.0 trillion U.S. budget deficits, and U.S. Treasury debt rising by $1.0 trillion every single year to finance those deficits, it is not surprising that economists (including us), and investors worry that the U.S. will eventually be unable to service its debt. We hope that Congress will act soon to rein in the skyrocketing budget deficits. Unfortunately, that is not going to happen any time soon. But foreign holders of U.S. Treasury securities seem equally unlikely to pull the plug and try to diversify their holdings. At some point perhaps, but not now.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me