September 21, 2018

The tax cuts have been in place for almost a year. Trump tried to sell the notion that they would stimulate growth in the economy and generate enough additional tax revenue that budget deficits would disappear in the years ahead. Most economists did not buy into that scenario. They believed that the tax cuts would increase future budget deficits, perhaps significantly so. With almost a year’s worth of data now available, it appears that the tax cuts increased the budget deficit in year one, but their impact longer term has yet to be determined.

The tax cuts have clearly stimulated the pace of economic activity. Following unimpressive 2.0% GDP growth in 2015 and 2016 the economy has picked up speed. Growth accelerated to 2.5% in 2017, is expected to climb 3.1% this year, and likely to register 3.0% growth in 2019. The tax cuts have clearly worked their magic and lifted the economy onto a faster growth track.

But how long will this growth spurt last? Whether the tax cuts are deemed a success will depend critically on the longer-term prospects for GDP growth. We think that the tax cuts and deregulation will result in a faster pace of investment spending which will lift GDP growth to a sustained 3.0% pace for the foreseeable future – the new normal.

Others suggest that the stimulus to investment spending will fade by 2020 and growth will revert to 2.0% — the old normal. It is too soon to tell whether the tax cuts have permanently lifted the economy’s speed limit.

Can the recent data on tax receipts provide an early indication of which theory might be more accurate? Not really.

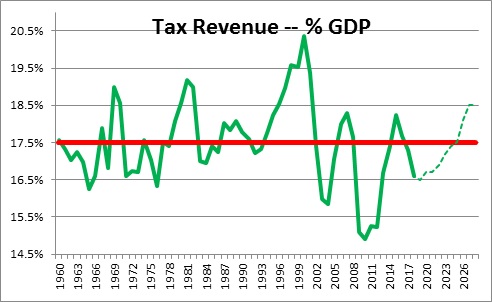

The idea that faster economic growth will bolster tax receipts by enough that budget deficits will shrink did not work out well this past year. Tax receipts should grow roughly in line with nominal GDP. If nominal GDP grows 5.0%, tax receipts should climb by 5.0%. That hasn’t happened. It appears that nominal GDP growth this year will be 6.0%, but tax receipts will edge upwards by just 0.7%. The economy grew more quickly this year, but the tax cuts took a significant bite out of tax revenue.

While the tax cuts negatively impacted the deficit in year one, if faster GDP growth is sustained won’t future budget deficits shrink? Perhaps.

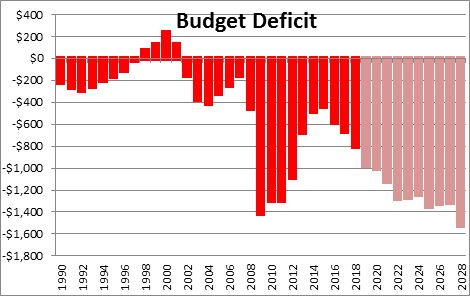

For the record, the budget deficit this year will climb from $665 billion to $800 billion . The Congressional Budget Office projects budget deficits exceeding $1.0 trillion every year for the next decade.

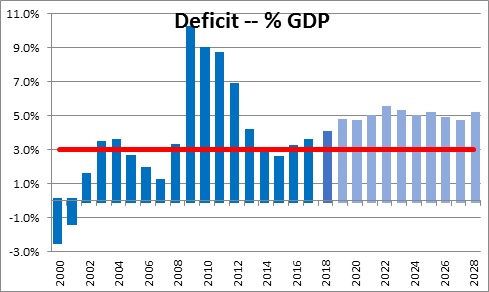

But deficit data only have significance when viewed in relation to the size of the economy. On that basis the budget deficit will be 4.0% of GDP this year. Economists believe that a budget deficit that is 3.0% of GDP is sustainable. Thus, the deficit currently is a bit high but not excessively so. The CBO expects it to quickly climb to 5.0% of GDP in the years ahead which will be a problem. But is it a lack of tax revenue or excessive spending that makes it so high?

Currently tax revenues are 16.5% of GDP which is somewhat lower than the long-term average of 18%. The CBO expects nominal GDP growth of 4.0% during this decade, tax revenues to grow somewhat more quickly than that, and reach 18.5% of GDP by 2028.

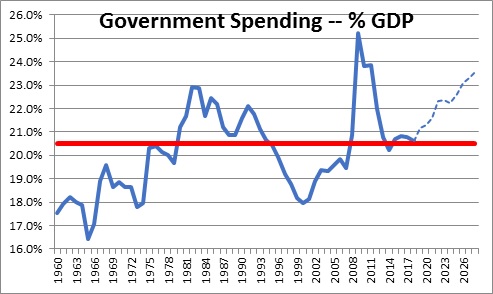

The CBO expects government spending to climb from 20.6% of GDP this year to 23.5% by 2028 which would be well above its long-term average of 21%. The pickup in spending is driven by demographics. The baby boomers were born between 1946 and 1964; they will retire between 2011 and 2029. As they retire they begin to receive Social Security benefits and become eligible for Medicare. Thus, the surge in spending is built in the cake.

But consider this. The CBO’s estimates of tax revenues are based on nominal GDP growth of 4.0% in the years ahead, presumably consisting of real GDP growth of 2.0% combined with 2.0% inflation. But suppose we are right and real GDP growth averages 3.0% during this period rather than 2.0%. Tax revenues in the years ahead will grow 1.0% more quickly than the CBO expects, and the deficits will be about 1.0% smaller. So rather than 5.0% of GDP, if the tax cuts boost potential growth to the 3.0% pace we expect, the deficits as a percent of GDP might be only 4.0%. Prior to the tax cut legislation, the CBO projected budget deficits of 5.0% of GDP. If the tax cuts stimulate potential GDP growth to 3.0%, then over the long-haul they will result in smaller budget deficits than would otherwise have been the case. The tax cut, however, would not – as Trump hoped — boost tax revenues sufficiently that budget deficits disappear.

Future budget deficits currently look problematical. We need faster potential growth to shrink them to a more manageable level. Time will tell.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me