November 25, 2016

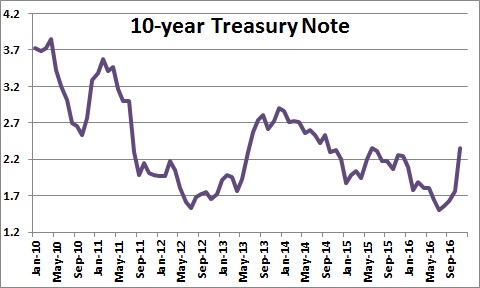

Following the election long-term interest rates have spiked upwards. Some worry that higher rates will weaken GDP growth in 2017. We doubt it.

The reaction in the bond market was in response to President-elect Trump’s economic agenda.

- Consumers will benefit from a sizable tax cut with the largest tax reductions for the middle class.

- Trump plans to cut the corporate tax rate from 35% to 15%.

- He wants to unlock trillions of dollars of profits currently locked overseas by allowing multi-national firms to repatriate off-shore earnings to the U.S. at a favorable 10% tax rate.

- He intends to reduce the onerous regulatory burden by eliminating unnecessary, duplicative and confusing regulations.

In short, the U.S. economy is expected to receive considerable fiscal stimulus in 2017 and beyond.

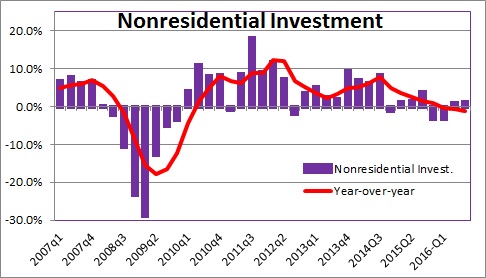

The combination of these factors will, in our view, unleash a wave of investment spending. Investment has been essentially unchanged for the past three years. We expect it to climb 2.5% or so in 2017, and perhaps twice that rate in subsequent years.

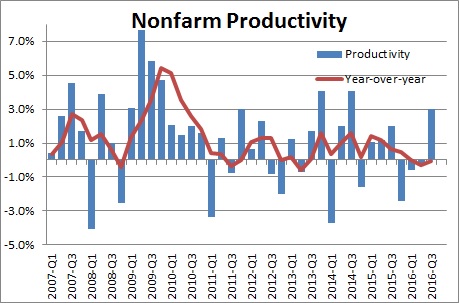

Given that investment spending is a major determinant of productivity growth, we also expect productivity to accelerate in the years ahead. It, too, has been largely unchanged for the past several years. If firms begin to spend money to implement the latest technology and/or refurbish equipment on the factory floor, productivity should flourish.

Faster productivity growth will, in turn, raise the economy’s speed limit. Currently, economists believe that rate is about 1.8% (consisting of 0.8% growth in the labor force and 1.0% growth in productivity). If, as described above, faster investment spending lifts productivity growth from 1.0% to 2.0%, then the economy’s speed limit will climb from 1.8% to 2.8%.

Faster productivity growth also helps to keep inflation in check. If firms pay their workers 1% more money but they are no more productive, then unit labor costs (or labor costs adjusted for the increase in productivity) have risen which means that the firm will probably be inclined to raise prices to counter the higher wages. But if they pay them 1% more money and they produce 1% more output, the firm will have no need to raise prices. Inflation will be stable.

Given that the yield on the 10-year note has risen 70 basis points from 1.7% to 2.4% in the couple of weeks since the election it is clear that the market is concerned about a faster rate of inflation.

However, we believe that faster productivity growth will counter much of the tendency for inflation to rise. For example, compensation) is currently climbing by 2.3% while productivity is flat at 0.0%. Hence, unit labor costs are rising by 2.3%. Next year we expect worker compensation to accelerate to 3.7%. We also believe productivity growth will pick up to 1.2%. That implies unit labor costs in this instance will increase 2.5% — which is little different from the 2.3% increase we have seen in the past year. The key will be whether productivity gains offset much of the increase in compensation. If they do, inflation will not accelerate in any meaningful way. That is our bet.

How will the Fed respond? We believe that the core CPI (i.e., excluding the volatile food and energy components) will rise 2.7% in 2017 versus 2.3% this year. However, the Fed inflation‘s target is not the CPI but the personal consumption expenditures deflator which tends to be about 0.5% lower than the CPI. Thus, the core PCE deflator should rise 2.2% next year compared to the Fed’s targeted inflation rate of 2.0%. That is not sufficiently different from its objective to force the Fed to accelerate the pace of tightening beyond what it has previously described. It expects the funds rate to be 1.0% at the end of 2017.

The recent increase in long rates since the election is partially justified give the expectation of considerable fiscal stimulus next year. However, if productivity gains prevent the inflation rate from rising rapidly next year and the Fed continues to raise rates very slowly, then we believe little further increase in long rates is in store between now and the end of 2017. Specifically, we expect the yield on the 10-year note to be 2.6% at the end of next year compared to today’s level of 2.4%. As shown above, the rate on the 10-year note was above 2.2% for most of 2013, 2014, and 2015 with no adverse consequences. So while long-term rates have risen sharply in recent weeks they should soon plateau at something close to their current level.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me