April 28, 2023

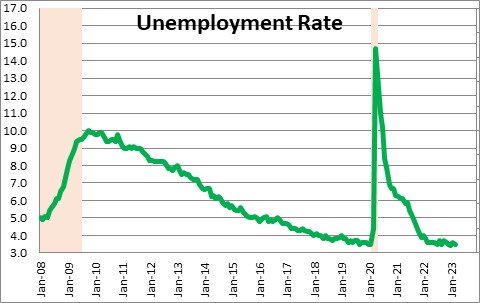

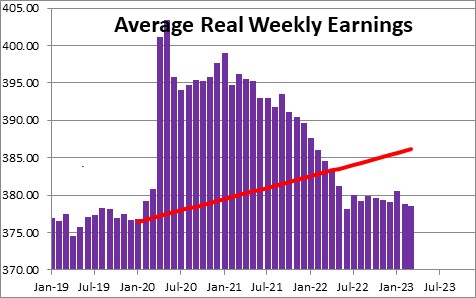

One of the biggest economic puzzles today is the surprising divergence between consumer confidence, which has plummeted, and consumer spending which has continued to climb at a moderate pace. That makes absolutely no sense. If we are as scared as we seem to be, then why hasn’t consumer spending fallen sharply? One possibility is that the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low of 3.5%. If someone loses their job it does not matter much. They can easily find another. With no fear of their income stream being interrupted, why cut back on spending? A second possibility is that real weekly earnings are not as far below where they ought to be as they seem. It is true that real weekly earnings have fallen for two years. But that ignores the fact that real weekly earnings surged in 2020 and 2021 as the government supplemented consumer income with huge stimulus checks. Thus, the decline in real weekly earnings in the past two years came from an artificially inflated level. If real weekly earnings had continued to grow at the same pace as they had prior to the recession, the current shortfall would be only about $8.00 per week ($0.20 per hour) or 2.0% higher than they are currently.. We are not as bad off as many suggest.

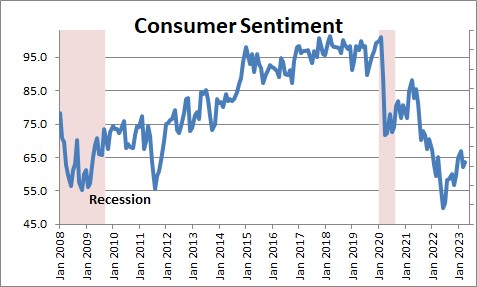

Consumer sentiment has plunged since the inflation rate began to climb in early 2021. It reached a low point in June 2022 which was far below the level of sentiment that existed at the bottom of the 2020 recession when consumers were petrified about the pandemic which had no available vaccine, and the government shutdown which caused GDP to fall 30% in the second quarter. Also, the June 2022 level of sentiment was roughly in line with the lowest level attained in the 2008-09 recession. That was billed as “The Great Recession”. It makes no sense (to us) that Americans are as nervous today as they were in those two earlier periods.

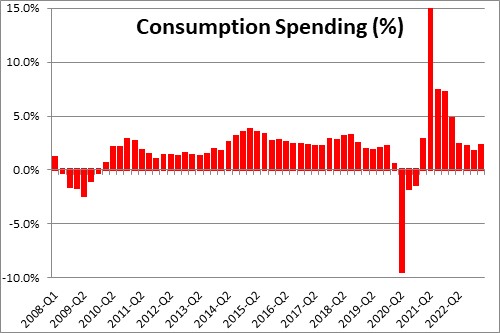

If we are so fearful why has consumer spending not declined? It fell sharply in 2008-2009, and then plunged in 2020. But yet this time, when we are seemingly as nervous as we were then, consumer spending has been chugging along at a respectable 2.3% pace.

The relationship between many economic variables has changed dramatically since the pandemic, and this is one of the more puzzling discrepancies. We suggest that one of the reasons why spending has not fallen is because the unemployment rate is completely unlike what it was in those two earlier recessions. The unemployment rate peaked at 10.0% in 2009. It peaked at 14.7% in 2020. Consumers had a legitimate reason to be worried. If they lost their job during those recessions they were not going to find a replacement quickly. But today the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low of 3.5%. The full employment threshold is assumed to be 4.0%. At that level everybody who wants a job has one. If someone gets laid off today, why worry? They can easily find another job. With no worry about their income stream being interrupted, there is little incentive to significantly reduce spending.

It has been widely noted that real earnings have been falling for the past two years. As real wages decline consumer purchasing power is reduced. Both statements are true. But nobody seems to point out that real weekly earnings surged in the second half of 2020 and all of 2021 when the government was passing out stimulus checks. Nominal and real weekly earnings surged during that 2020-21 period and consumer purchasing power skyrocketed. Consumers responded and began to spend vigorously. Firms were unable to boost production as rapidly as spending rose and, not surprisingly, the result was a dramatic pickup in the inflation rate. Earnings growth is yet another economic indicator that has been significantly distorted by the pandemic and the government’s response to it.

Given these wild swings in real weekly earnings, we wonder where real earnings would have been if they had continued to grow at their pre-recession pace. That path is shown by the red line above. Real earnings today are less than where they presumably would have been in the absence of the recession and subsequent stimulus, but not by a lot. As shown, the difference today – three years later — is about $8.00 or 2.0%. To say that real earnings have been falling for the past two years creates an impression that consumers are in bad shape. Press articles highlighting that fact may be contributing to consumers surprisingly low level of confidence. But if consumer earnings are only slightly lower today than they were three years ago, consumer purchasing power has not fallen as much as one might think and, hence, they keep spending.

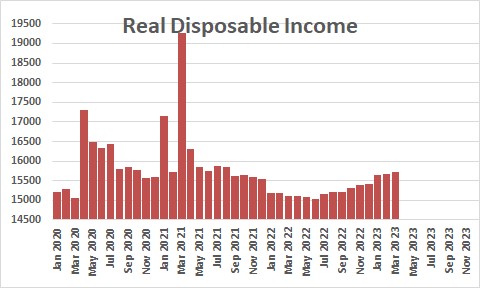

In the end, there is no doubt that consumer purchasing power is being eroded by inflation, but now that the inflation rate is gradually subsiding and real disposable income is once again climbing, real weekly earnings may soon turn upwards which will keep the economy going. We will see.

Stephen D. Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen, I think you have the right answers to your questions. It is amazing what happens when unemployment remains low and the jobs are out there or the picking. Good analysis on your part.

Thanks Darrel. It certainly becomes difficult when the pieces do not fit together the way they used to. And economists love to rely on history for guidance. Good luck with that.

Steve

Brilliant summary of this complex conundrum. While the conflicting signals are clear to those who follow economic news, making sense is hard, but you do it masterfully.

Thanks TYson.