April 20, 2018

The IMF recently updated its global economic forecast which included a review of the U.S. situation. In the past six months it has boosted its estimate of U.S. GDP growth for 2018 and 2019 by 0.6% and 0.8%, respectively, to 2.9% and 2.7%. The upward revisions reflect the stimulative impact provided by the tax cuts approved by Congress in December of last year, and the increase in defense spending incorporated in the budget legislation passed In January. The IMF’s growth outlook for these two years is similar to ours. However, the IMF envisions a significant slowdown with GDP growth rates between 1.4% and 1.9% in the 2020-2023 period which is considerably less than the 2.8% we anticipate.

For the record, we are always interested in growth projections provide by the IMF. This international organization has some of the smartest, hardest-working, dedicated economists in the business. Its projections are always comprehensive, logical, and free of political bias. Whenever its forecasts differ from our own we want to understand why. In this case, the difference centers on the longer-term impact of the tax cuts on investment spending, productivity, and potential GDP growth.

The IMF believes that “weak productivity trends and reduced labor force growth due to population aging constrain medium-term prospects”. It expects potential growth to remain between 1.4% and 1.9%. The IMF believes the relatively rapid rates of GDP growth in 2018 and 2019 will reduce the unemployment rate to 3.5% which will eliminate any remaining slack in the labor market. The additional labor market tightness will accelerate growth in wages and push the inflation rate 0.5% or so above the Fed’s 2.0% target. Against this background the Fed will steadily raise interest rates to a level that will eventually dampen GDP growth to 1.4-1.9% which it believes is the economy’s longer-term sustainable growth path. As economic activity cools, the inflation rate returns to the Fed’s desired 2.0% pace and the Fed stops raising rates. Thus, the IMF envisions an economic expansion that will continue for the next six years, but with a slower pace of GDP growth in the outyears than we would anticipate. It is a perfectly plausible scenario, but it assumes little longer-term impact on investment spending, productivity, and potential growth. We anticipate faster growth for all three.

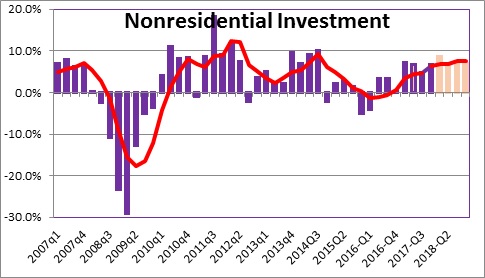

Here is our alternative scenario. We believe, as does the IMF, that tax cuts will stimulate the economy for the next couple of years. But there is more going on than just tax cuts. Nowhere does the IMF talk about the deregulation that has occurred in the past year and is ongoing. For years the corporate world and small businesses complained endlessly about the regulatory burden which was stifling their desire to expand. As a result, investment spending came to a screeching halt in 2015 and 2016. But the moment Trump was elected in November 2016, investment spending began to accelerate. In the four quarters of 2017 such spending climbed at rates of 7.2%, 6.7%. 4.7%, and 6.8%. That is in sharp contrast to the distinct lack of growth in the previous eight quarters. The tax cuts were not passed until December of last year, so the growth pickup was not caused by the lower corporate tax rate.

We would suggest that the speedup reflects the steady elimination of confusing, duplicative, and often unnecessary regulations. Trump claims to have stalled or killed 860 pending regulations. While that assertion is almost certainly exaggerated because many of those regulations had not yet been implemented, there is general agreement that Trump has launched an aggressive attack on regulations covering everything from climate change to financial transactions. The business community is justifiably elated when a regulation is eliminated – even if that regulation had not yet been fully implemented. Investment spending will benefit further if policies to discourage new regulations are put into place. Thus, Trump’s de-regulation initiative is likely to stimulate investment spending for years to come.

Keep in mind, also, that tightness in the labor market will encourage business leaders to invest. If the unemployment rate falls to 3.5% and new workers are hard to find, one way to boost output is to invest. Business types may well choose to spend money on new technology, re-furbish equipment on the assembly line, or build a new factory to keep production humming.

We believe the combination of tax cuts, regulatory relief, and a tight labor market will stimulate investment spending for years to come.

Because investment spending is the main driver of productivity, productivity growth should quicken from 1.0% or so today to 2.0% by the end of this decade. Coupling that with 0.8% growth in the labor force will produce potential GDP growth of 2.8%. That is far higher than the IMF’s 1.4-1.9% expectation.

The difference between our forecast and that of the IMF centers on the reaction of business people to the combination of tax cuts, deregulation, and a tight labor market. We are clearly more optimistic than most. If we are correct, the economy and our standard of living will grow more quickly, inflation will remain in check, and the Fed will not need to raise rates to a level that could jeopardize the expansion. It is an important difference.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Steve,

Your interpretation is fascinating. Much food for thought. Thank you again for your insights. They are reassuring in the face of confusion,

Darrel

Very interesting and clear article, thank you