February 18, 2011

With the release of the January CPI report, the inflation hawks are claiming that inflation has begun to climb, that the Fed is way behind the curve, and that it needs to raise rates sharply to prevent those recent gains from becoming entrenched. While any suggestion that inflation is on the rise is worrisome, sometimes that fear can be exaggerated. Let’s try to examine this inflation dispassionately.

Consumer prices rose 0.4% in January after having risen 0.1% in November and 0.4% in December. This means that during the most recent three-month period the CPI has risen at a 3.8% annual rate which compares to an increase of 1.6% during the past year. On the surface, inflation appears to be accelerating.

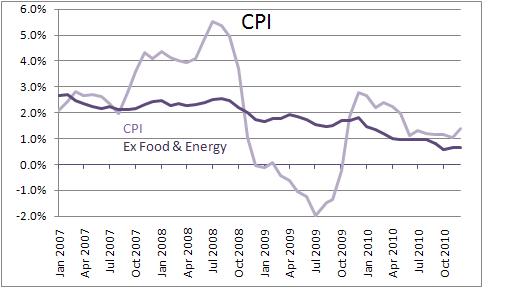

However, about two-thirds of the overall increase in that three month period is energy-related. The problem is that energy prices are notoriously volatile, and what appears to be a problem today can reverse direction and be far less threatening in just a few short months. The chart below indicates that in 2007 and the early part 2008 energy prices rose rapidly, they plunged during the recession, climbed again in late 2009, and then worked their way lower.

Given this volatility, it is hard to know what is happening to the trend rate of inflation. Thus, economists like to focus on the CPI excluding the volatile food and energy components which is rising at a much less troublesome rate. In the past three months this portion of the overall index has risen at a 1.4% pace versus 1.0% in the past twelve months. Given that the Fed has been worried about deflation, one could argue that such a modest acceleration in consumer prices is actually a positive development.

Immediately, those people concerned about inflation will point out that we must buy food and fuel, so they should not be excluded. That is absolutely correct. But the issue is whether the Federal Reserve should respond to an increase in the inflation rate caused by a run-up in energy prices. It is important to recognize that the Fed cannot control oil prices. They are going to rise or fall completely apart from any policy action the Fed might pursue.

But that does not mean that the Fed is helpless. It clearly has the tools to fight inflation no matter what the source. If they were so inclined they could quickly push interest rates higher to combat a pickup in inflation, but at what cost? Such action now would almost certainly dump the economy back into recession, the unemployment rate would rise again, and prices of non-energy related goods and services would decline. But if the problem in the energy sector is related to political issues in the Middle East, oil prices are not going to fall. To push the economy back into recession to fight a source of inflation that it cannot control does not seem like an appropriate course of action for the Fed.

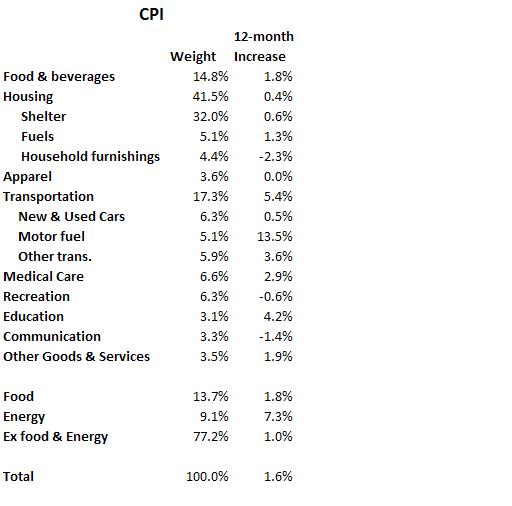

Their action should depend upon a potential increase in inflation caused by non-energy-related prices. With that in mind, let’s take a look at the composition of the CPI and its components.

Food prices have risen 1.8% in the past year and are not a big problem currently.

Housing accounts for 41.5% of the overall index. What happens to this category is crucial. As shown in the table has risen just 0.4% in the past year – even with an increase in fuel oil because that increase is being partially offset by falling prices for electricity. Then look at the prices for household furnishings. They have fallen 2.3% in the past year. No problem here.

Apparel prices have been unchanged.

Transportation prices have risen 5.4% but that increase is largely fuel-related. New and used car prices have risen just 0.5% in the most recent 12-month period.

Medical care, which is always a rapidly rising component of the CPI has risen 2.9%. For purposes of comparison, medical costs rose 3.4% in 2009 and 3.3% in 2010. If anything, the rate of increase in medical costs seems to be slowing.

Recreation prices have declined 0.6%. This reflects the falling prices of CD’s and DVD’s.

Communication equipment which includes personal computers and software as well as telephone services has declined 1.4%.

It is very easy to get caught up in looking at selected components that are rising rapidly. Those are eye-catching and stoke fears of an immediate pickup in inflation. We easily forget about those components of the CPI that are rising only slowly or, in some cases, actually declining. But we shouldn’t dismiss these components. They are an important part of the overall inflation outlook.

For now it is hard to see why the Fed would be worried about an increase in inflation.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Very nicely explained. Thank you.