November 30, 2018

Most economists believe that the economy is growing at a rate well in excess of its assumed potential growth path. That should translate into upward pressure on the inflation rate. The problem is, that is not happening. If the upswing in inflation continues to be more gradual than the Fed expects it may postpone further rate hikes. Why isn’t inflation rising more rapidly?

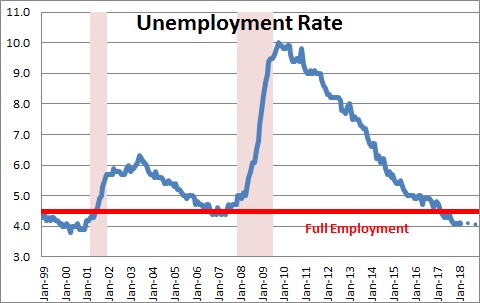

Economists believe that the “full employment” threshold is somewhere around 4.5% because at that point wages began to climb.

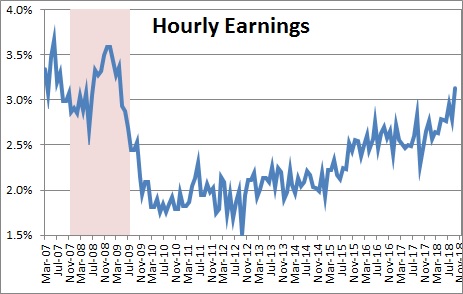

Currently, the unemployment rate is 3.7% and average hourly earnings have risen steadily from 2.0% a couple of years ago to 3.1%. Because wages are rising more rapidly than the Fed’s 2.0% inflation rate, many economists worry about upward pressure on the inflation rate.

But we have often said that by focusing on measures such as average hourly earnings, economists are looking at the wrong thing. They should be focusing on labor costs adjusted for changes in productivity which are known as “unit labor costs”.

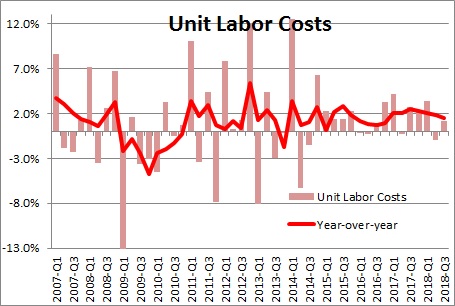

If I pay you 3% higher wages, you might think that my labor costs have risen by 3.0% and I will be tempted to raise prices to offset the higher cost of labor. But what if I pay you 3.0% higher wages because you are 3.0% more productive? I really do not care. I am getting 3.0% more output. You have earned your fatter paycheck. In this case “unit labor costs”, labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity, are 0.0%. I have no reason to raise prices.

Unit labor costs data are included in the productivity report. In the past year compensation has risen 2.8% while productivity has climbed by 1.3%. Thus, unit labor costs have increased by 1.5%. The Fed has a 2.0% inflation rate. Economists who look at the 3.1% increase in average hourly earnings conclude that the seemingly tight labor market will put upward pressure on the inflation rate. But if one factors in the increase in productivity and learns that unit labor costs are rising 1.5%, there is no upward pressure on the inflation rate despite a seemingly tight labor market.

One other thing. The Fed believes that the economy’s “potential growth” rate is 1.8%. That consists of 0.8% growth in the labor force combined with 1.0% growth in productivity. Our theory is that the impressive pickup in investment spending will gradually lift productivity growth to 2.0% and, by the end of this decade, potential growth will climb from 1.8% to 2.8% consisting of 0.8% growth in the labor force combined with a 2.0% increase in productivity. Recent data suggests that we are on the right track. In the past two quarters productivity rose 2.9% in the third quarter and 2.2% in the fourth quarter. The pickup in investment spending the past two years seems to be paying off in faster growth in productivity.

Having said all that, potential growth is a long-term concept and we are talking about short-term developments. Fair enough. But the fact that the economy has grown 3.0% in the past year with no real increase in inflation seems to suggest that the Fed’s 1.8% estimate of potential growth rate is way too low. We suggest that it may have already reached the 2.5% mark. For the Fed to reach the same conclusion it will need to see sustained growth in both investment spending and productivity. If productivity can grow at a 2.0% pace for three years or so, the Fed will eventually conclude that potential growth has risen to something like the 2.8% pace we are suggesting.

The recent increase in productivity can impact the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates. If Fed Chair Powell and his colleagues conclude that potential growth could be rising, they may refrain from further rate hikes. If the economy is growing by 3.0% and the Fed thinks potential growth is 1.8%, it should be tightening aggressively to prevent a pickup in inflation. But if the economy is growing at 3.0% and potential growth may have climbed to 2.5% or higher, perhaps it should sit tight for a while. The economy may not be exceeding the speed limit by much.

Besides, the funds rate is currently 2.2%. A neutral funds rate may be 3.0% but some officials suggest it could be lower, say, 2.5-2.75%. Thus, the funds rate may not be far from where it needs to be. Furthermore, the recent sharp drop in oil prices is almost certain to cause the overall inflation rate to decline in November and December. Thus, the Fed has the luxury of time to reassess its strategy. Chill.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me