April 21, 2023

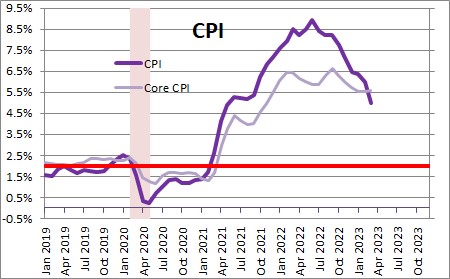

The biggest mistake the Fed has made in recent years was believing that the run-up in inflation that began once the recession ended in April 2020 was going to be temporary. Fed officials maintained that view for 20 months. It was not until December 2021 they finally concluded that it was not as temporary as they thought, and that they needed to dramatically increase the level of the funds rate. The funds rate then climbed from 0% in March 2022 to its current level of 5.0%, We never believed that the run-up in inflation was temporary but was, instead, being caused by unprecedented growth in the money supply. Money growth created surplus liquidity in the economy which was the catalyst for the acceleration in the inflation rate. Since the beginning of this year the money supply has been contracting steadily. While surplus liquidity remains, if the Fed keeps shrinking the money supply at its current pace that surplus liquidity should disappear by yearend. Once that happens, inflation will eventually return to its 2.0% targeted pace.

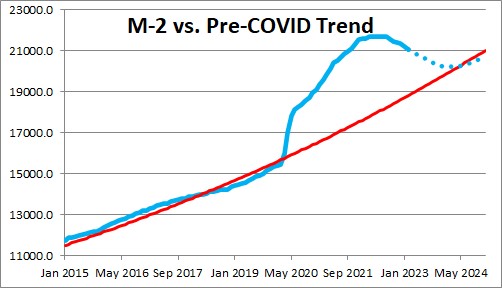

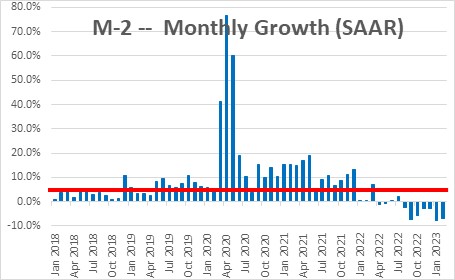

The money supply is not something that most economists talk about these days but, in our view, money matters. The most widely known measure is M-2, which consists of whatever cash is in our wallets,and balances in our checking accounts, money funds and other liquid assets that could be used to buy something this afternoon if we chose to do so. It is simply a measure of liquidity in the economy. It typically grows roughly in line with nominal GDP. Historically, that growth rate has been about 6.0%. For years the level of the money supply tracked closely along its 6.0% growth path.

But along came the pandemic and the dramatic 30% decline in second quarter GDP as the economy stopped dead in its tracks. To get it turned around the Fed purchased $2.5 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities in March and April 2020. But the Fed did not stop there. By March 2022 the Fed had purchased another $1.7 trillion of securities. Growth in the money supply far exceeded the 6.0% desired pace each month from March 2020 through December 2021. As it continued to grow at an excessive rate, the level of M-2 moved farther and farther above where it should have been. At its peak in December 2021 the money supply was $4.0 trillion higher than the appropriate level. That meant the economy had $4.0 trillion of surplus liquidity. No wonder we have an inflation problem!

In December 2021 the Fed finally stopped buying Treasury securities and by March 2022 it began to raise the funds rate steadily from 0.0% to its current level of 5.0%. Money growth began to decline in August of that year and has fallen every month since. As a result, the money supply is no longer $4.0 trillion higher than it should be but, rather, $2.3 trillion above target. It is moving in the right direction, but it will take time to get back to where it belongs. If the Fed continues to shrink the money supply at its current pace that will happen by the end of this year.

If excessive growth in the money supply caused the recent run-up in inflation, then lowering it to an appropriate level will eliminate the surplus liquidity and allow inflation to return to the 2.0% mark.

We believe that the core CPI, which has risen 5.6% in the past year will slow to 4.7% by the end of this year, and then continue to drop to a 3.0% pace by the end of 2024. The Fed does not target the core CPI but, rather, the core personal consumption expenditures deflator which runs about 0.3% lower than the CPI. The Fed thinks the PCE deflator will rise 3.6% this year and 2.6% in 2024. Translating that into a CPI equivalent by adding 0.3% to each number, suggests the Fed anticipates the core CPI will rise 3.9% this year and 2.9% in 2024. But the Fed also expects the economy to slip into a recession in the second half of this year. If we anticipated a second half recession we would likely have a 2023 projected inflation rate of 3.9% rather than the 4.7% we currently expect in the absence of a recession.

The bond market, like the Fed, seems to be expecting a second half recession. The market believes that the Fed will raise the funds rate one more time to 5.25%, but then lower rates to 4.75% by the end of the year. But if the inflation rate remains as high as the Fed expects (3.6% for the core PCE deflator or 3.9% for the core CPI), the Fed cannot afford to lower rates so quickly. Doing so would suggest that it has given up on achieving a 2.0% inflation rate. For what it is worth, we expect the Fed to raise the funds rate to 6.0% by the end of this year which is far higher than the 5.1% mark which the Fed expects and the 4.75% rate the market anticipates.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen, I read your analyst weekly, trying to understand exactly where things are headed with inflation, interest rates, GDP etc. This week you really made things clear for the layman. I greatly appreciate your brilliant analysis. Since I have been following you for many years now, I find you are almost always right on track. Thank you for understanding and explaining what is happening in the present and the future of our monetary situation.

Kudo to you.

Darrel Staat

Hi Darrel. Thanks so much for the kudos.

As it turns out the money supply is near and dear to my heart. When I first got out of school I got a job at the Board of Governors of the Fed producing those money supply statistics and making forecasts of them for the Board. This was back in the early 1970’s. I also happened to be there when Volcker decided to stop targeting interest rates and began targeting money supply growth. That was truly exciting! At first, we had no idea exactly how to do that so there was a lot of tinkering but we eventually got better at it. Ever since then I have diligently followed money growth. Most of the time it does not matter too much because its growth rate is fairly steady. But I am convinced it kept me out of trouble in trying to explain the 2021-2022 runup in inflation.

Steve