November 1, 2024

Inflation fears have permeated the bond market as the yield on the 10-year note has risen 0.7% since mid-September. This dramatic increase seems to reflect inflation concerns stemming from the policies advocated by both presidential candidates. Rising inflation would clearly be disturbing should it arise. But will it? There are four reasons we believe that inflation will remain in check for the foreseeable future. First, slow growth in the money supply has eliminated almost all of the surplus liquidity that existed in mid-2022. Second, productivity gains have raised the economic speed limit and the economy can comfortably grow at roughly a 3.0% pace today without giving rise to inflation. Third, wages have been rising at about a 4.0% pace, but productivity gains have reduced growth in unit labor costs (the cost of labor per unit of output) almost to 0%. This means that there is no upward pressure on inflation stemming from a still tight labor market. Finally, the rent component of the CPI, which accounts for one-third of the overall index, continues to slow. Rents reflect home price increases that occurred about 15 months ago. With a still relatively anemic housing market it is hard to envision sharply rising home prices any time soon. Given all these factors we believe that, in contrast to the market’s fears, the inflation rate will gradually slow further to the Fed’s 2.0% target by mid-2025.

In six weeks the yield on the Treasury’s 10-year note has risen 0.7% from 3.6% to 4.3%. That is a breathtaking increase in a very short period of time. It seems to reflect a growing nervousness about the inflation outlook. The run-up in long rates coincides with a growing focus on the policies advocated by both Trump and Harris, The nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget says that both candidates are advocating policies that will substantially increase budget deficits and debt outstanding over the next 10 years which could lead to a higher inflation rate and higher long-term interest rates.

But while the fear of a rising inflation rate has been spreading in recent weeks, the question is whether those fears are legitimate. We suggest that the fear is misplaced for several reasons.

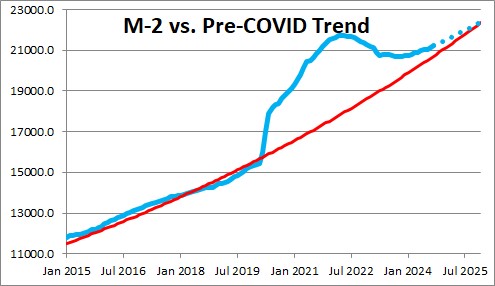

First, the growth rate in the money supply declined steadily from April 2022 through the end of last year. It has stopped falling and begun to grow at a modest 3.4% pace in the past six months. As a result, most of the excess liquidity created by the Fed’s bond-buying initiative from the end of the recession through March 2022 has been largely eliminated. If the Fed continues to shrink its balance sheet, the remaining excess liquidity should be eliminated by early next year. That, in turn, should allow the inflation rate to continue to slow gradually in the months ahead.

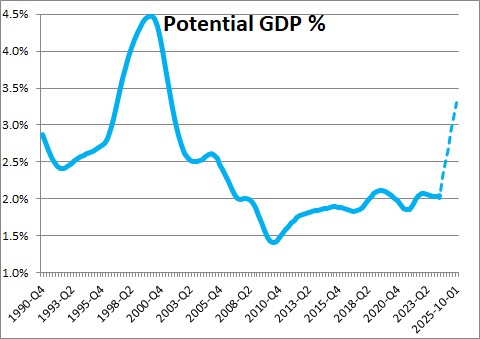

Second, the economy’s potential growth rate (the speed limit for non-inflationary growth) has climbed from 1.8% prior to the recession to about the 3.0% mark. It can be estimated as the sum of the growth rate for the labor force plus the growth rate for productivity, Previously economists combined 0.8% growth in the labor force with 1.0% growth in productivity to come up with an estimated potential growth rate of 1.8%. But productivity growth has accelerated to almost 3.0%. Redoing the equation by combining about 0.5% growth in the labor force with a guestimate of 2.5% productivity growth in the quarters ahead, comes up with a far more rapid potential GDP growth rate of 3.0%. In the past year GDP growth has risen 2.7% and economists expect a similar or slightly slower growth rate in 2025. If the new estimate of potential growth is relatively accurate growth of that magnitude should not exert upward pressure on the inflation rate.

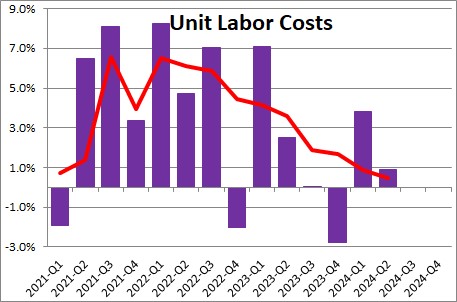

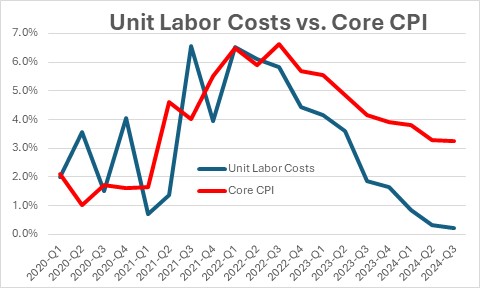

Third, wages have been rising by about 4.0%. With the unemployment rate at 4.1% the labor market is at full employment which means that everybody who wants a job has one. If the economy continues to grow at a relatively rapid rate, some economists fear that wages pressures could climb. But they are looking at the wrong thing. They should not be looking at the nominal increase in wages, but at unit labor costs. If employers pay workers 4.0% more money but those workers are 4.0% more productive, they have earned their fatter paycheck. Employers are paying their workers 4.0% more money, but they are getting 4.0% more output. That is essentially what is happening currently. In the past year worker compensation has risen 2.7% but productivity has risen 2.4%. As a result, unit labor costs have risen by just 0.3%.

If unit labor costs continue to rise slowly, the core inflation rate will trend lower. Given that labor costs represent two-thirds of a firm’s overall costs, that would bode well for the inflation outlook.

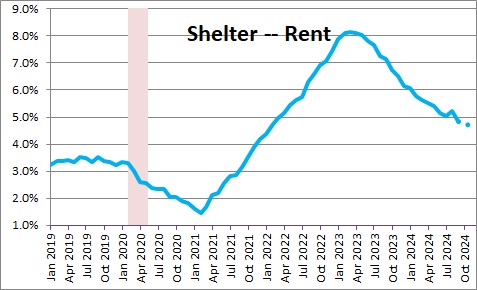

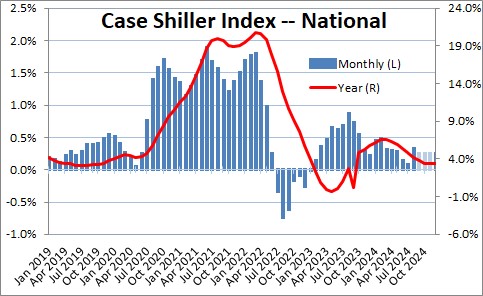

Finally, one of the most significant problems in preventing the core inflation rate from falling more quickly has been rapid growth in the rent component. At one point rents were climbing at an 8.0% pace. They have since slowed to 4.8% and are poised to slow further in the months ahead. This is a big deal because rents represent one-third of the entire CPI index.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics uses home prices as a proxy for the calculation of rents with a long lag. Thus, home prices are a leading indicator of the rent component about a year later. But the rate of increase in home prices has been slowing steadily since mid-2022. The 20% annual increases in 2021 and 2022 have given way to a 4.2% increase currently. With the housing market still sluggish it is hard to see how home prices could increase more rapidly in the months ahead. If that happens, the rent component should rise even more slowly in 2025.

The markets are correct in keeping a watchful eye on the inflation rate. But, as we see it, the inflation outlook seems particularly benign at least through the end of next year.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me