August 24, 2012

Interest rates in the United States are at record low levels. Currently, the Treasury relies heavily on short-term securities — bills and notes — to finance its debt. Bonds account for a relatively small portion of its funding mix. But within a year or two the Fed will begin to tighten, interest rates will rise, and the interest cost to the Treasury will climb. The Treasury is doing a disservice to the American people by not taking advantage of the current record low interest rates levels and issuing a far greater percentage of 30-year bonds. They might even think about introducing a 50-year or even a 100-year bond. Here’s why.

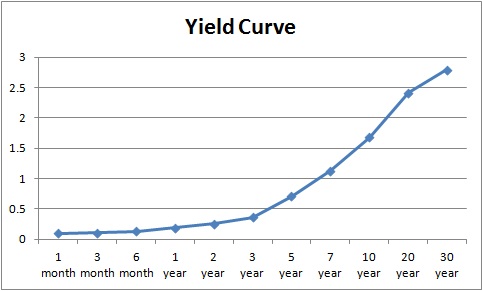

With the Fed currently pegging the overnight federal funds rate essentially at 0%, all Treasury bills and some short notes have rates of 0.25-0.50%. Longer-dated securities are slightly higher — 7-10 year notes have rates of 1.0-1.5%, and bonds yield 2.7%.

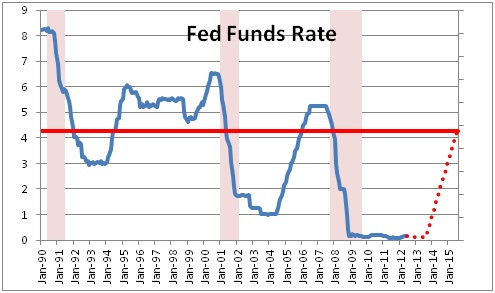

At the moment, 82% of Treasury securities outstanding are bills and notes. At first blush this seems to make sense given that it costs the Treasury almost nothing to issue these securities. The problem is that rates are not going to stay here forever. Indeed, the Fed has told us that it intends to leave the funds rate at its current near-zero level through the end of 2014. At that point it will shift gears and begin to push the funds rate higher. By doing so it will take its foot off the accelerator and shift into neutral.

Once the Fed starts to raise rates it will do so gradually, but it will go far. The Fed believes a “neutral” funds rate – where it is neither stimulating nor slowing the economy is 4.25%. If the Fed begins to tighten in late 2014 the funds rate should reach that higher level by late 2016. So instead of paying 0.25% for short-term debt, the Treasury will pay 4.25%. For every $100 billion of short-term debt it issues, its interest expense will have increased $4 billion. Eventually the Fed will feel compelled to slow the economy and short rates will climb further to say 6%, at which time the Treasury’s interest expense will be even higher.

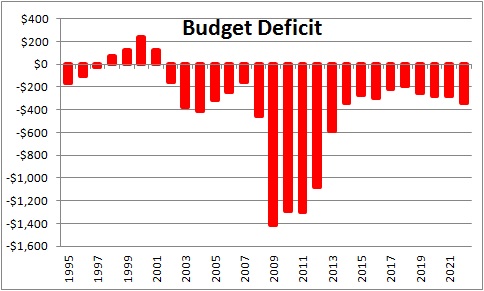

Is there some way to take advantage of today’s record low interest rate environment to lock in those reduced costs? Of course. The Treasury could increase the amount of 30-year bonds that it issues. Issuing a larger proportion of bonds is not unprecedented. In 2001, before the Treasury temporarily eliminated the 30-year following a series of budget surpluses (remember them??), bonds were 22% of Treasury securities outstanding. Today that percentage has been cut in half to 11%.

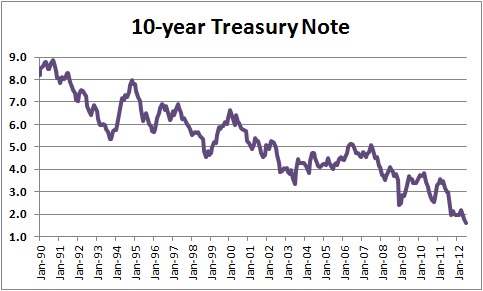

Rates on the Treasury’s 10-year note are comparable to the 30-year bond and, unlike the 30-year, have been available for decades. As shown below, today’s 1.6% 10-year rate has never been lower. The same is true for 30-year bond yields which are currently 2.7%. Why not take advantage of these record low rate levels and issue a much larger amount of 30-year bonds? In the near term the interest rate the Treasury will pay will be higher – 2.7% versus roughly 0.2%. That means that for every $100 billion of Treasury bonds issued, the cost today will be $2.5 billion higher than it would be to issue a comparable amount of Treasury bills and short coupons. But four years from now short rates will have risen to 4.25% and bond yields are likely to be around 6%. At that point the Treasury will begin saving an even bigger amount annually. To pay more interest for 4 years to save an even bigger amount for the next 26 years strikes us as being a no-brainer!

If all of this is correct, then why not go even farther and issue a 50-year or even a 100-year bond? While no market really exists for these securities at the moment, people said the same thing about the 30-year bond when it was introduced in the mid-1970’s. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that Goldman Sachs issued 50-year bonds in both 2010 and 2011. And the U.K. talked about issuing a 100-year gilt in March. The idea is for the U.S. to take advantage of its “safe haven” status which is attracting money from around the globe and pushing long-term interest rates to record low levels.

Seize the moment!

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me