June 15, 2018

The Fed’s rate hike to 1.75-2.0% this past week was widely anticipated. The modest surprise was that FOMC members are now leaning towards a total of four rate hikes this year. When they last met in early May the committee was split about whether to raise rates three times this year or four. Most major news organizations interpreted the Fed’s recent statement as a signal that faster rate hikes are on the way. That is not entirely accurate. The Fed told us in March that they plan to lift the funds rate to 3.4% by the end of 2020. That has not changed. They end up in the same place but given recent economic data they added an additional rate hike later this year. What caused the Fed to alter slightly its outlook for this year? Is the economy overheating? Is inflation picking up too quickly? Will the Fed’s rate hikes jeopardize the expansion? The short answer is – all is well and the economy is on track to expand beyond 2020.

The catalyst for the Fed was a string of strong economic statistics. Payroll employment jumped 223 thousand in May. The unemployment rate declined 0.1% to 3.8% and (at 3.754%) was on the cusp of a 0.2% drop to 3.7%. Fueled by tax cuts, retail sales surged 0.8% in May. Combining these tidbits suggests that GDP growth could quicken to a 4.0% pace in the second quarter. Interestingly, the same folks who are now worried that the economy is overheating are the same people that were worried about slow growth a couple of quarters ago. While the economy may be accelerating in the second quarter be careful. First quarter GDP rose at a modest 2.2% pace. In recent years GDP has tended to register anemic growth in the first quarter followed by a rebound in the second, and trend like growth in the second half. Thus, the trend rate for the first half of the year is about 3.0%. While faster than the 2.6% pace registered in 2017, it can hardly be construed as a dramatic pickup.

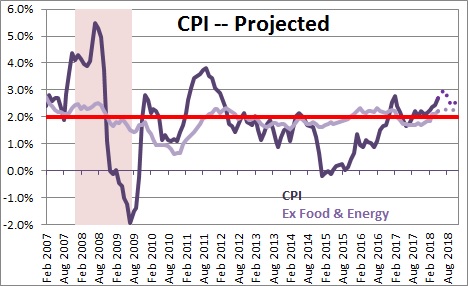

Meanwhile, the core CPI for May rose 0.2%. Its year-over-year growth rate is 2.2%. This rate has been inching its way higher, but the operative word is “inching”. For what it is worth, we expect the core CPI to rise 2.3% in 2018. If that is accurate it is not going to bother the Fed. However, 3.0% GDP growth and a steady pickup in inflation ensure that the Fed remains on track for gradually rising interest rates.

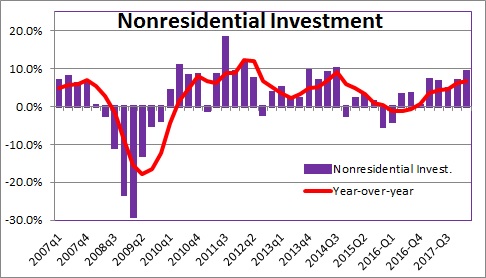

What makes our forecast different from others is that we believe that an impressive pace of investment spending in the wake of the corporate tax cuts will stimulate productivity growth. That will, in turn, boost potential GDP growth from 1.8% for the past couple of years to 2.8% by the end of the decade. If that is the case, our projected 3.0% GDP growth path will not lead to any meaningful pickup in inflation. However, this is a forecast and could be wrong. If productivity does not pick up, 3.0% GDP growth will almost certainly lead to higher inflation. Thus, we must monitor closely GDP growth, productivity, and inflation in the quarters ahead.

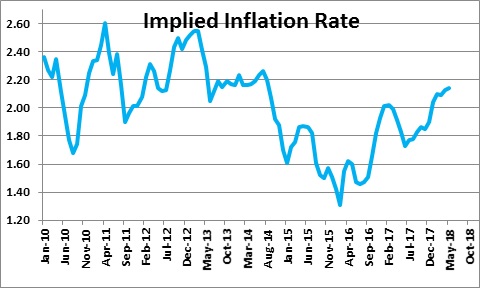

Thus far the markets do not seem worried that the faster current rate of GDP growth and the gradual upswing in inflation will be a problem. Comparing the nominal interest rate on the Treasury’s 10-year note to its inflation-adjusted equivalent provides a market-based estimate of inflationary expectations. This rate has been gradually rising for the past two years but, at 2.1% currently, participants are clearly not alarmed. The Fed would be concerned if that rate were to pick up markedly because a pickup in inflationary expectations often leads to a pickup in the actual inflation rate. If the economy is overheating and the Fed is not raising rates quickly enough, businesses will anticipate higher inflation and begin to raise prices. If expectations were to climb to 2.5% the Fed would almost certainly accelerate its pace of tightening and more quickly return to a neutral funds rate which it believes is around the 3.0% mark. That is not our call, but it is something to watch.

For the economy to slip into recession we need two things. First, the funds rate must climb a couple of percentage points above the neutral rate to perhaps 5.25%. Second, short-term interest rates must become higher than long rates (which means that the yield curve” inverts”). With the rate on the 10-year not at the end of 2020 likely to be 4.2% and the funds rate at 3.5%, the yield curve would retain its positive shape. Neither of the two requirements for a recession are on the horizon. A recession is looming out there somewhere, but not through the end of 2020.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Stephen,

Good to have you back. I hope you had a wonderful vacation. I am ready to be kept up to date again on what is happening to the economy.

Darrel

Although the economy looks far from being on a cusp of another recession, the SPY is reaching all-time highs on an hourly basis. Would you care to address some of your valuable thoughts on the current stock market and its longevity? Thanks!

Hi Ray,

Let me preface this by saying that I am an economist, not a stock guy.

Having said that, the economy and the stock market are clearly different animals but they are related via growth in corporate earnings. If you buy my world where the economy continues to chug along at least through 2020, inflation edges its way upwards, the Fed continues to raise rates slowly, and government regulation continues to abate, then the stock market should continue to climb as well. But nothing moves in a straight line. The stock market has its short-term wiggles but its trend should remain upwards. We would take a stab that it gets to 3,000 by the end of this year, and grows by something in the mid- to upper- single-digits in 2019 and 2020.

Steve Slifer

Hi Darrel,

Vacation was good. Spent some time in Russia.

Upon my return, the economy still looks good. Very good in fact despite all the noise about trade. As always, we will see.

All the best.

Steve

Hi Steve,

Thanks for sharing your take on the stock market.

If what you described proves to be true, 3000 by year end, 5% a year for 2019 and 2020, that takes sp500 to 3300 mark which is scarily high at an unprecedented bull market. What fuels this and where does all this money come from? All this QE money from central banks around the globe?

Best regards,

Ray

I am an economist and not a stock guy. I never provided those S&P numbers that you cite. Having said that, I do believe the stock market can keep climbing — in its usual erratic fashion. If, as I suspect, the economy keeps growing at a rate close to 3%, if the Fed raises rates in the slow methodical fashion it has described, then the S&P numbers that you cite are not unattainable. The key is continued growth with relatively low inflation. Just because the bull market is now the longest on record does not mean that it cannot continue for a while longer.