June 9, 2023

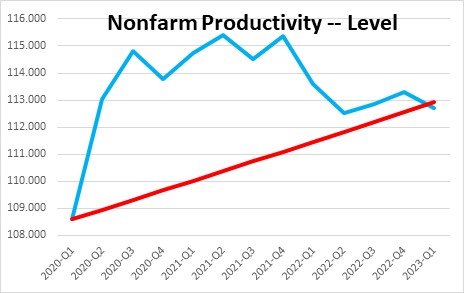

Much has been written recently regarding the recent disquieting decline in productivity. The productivity drop suggests that firms are hanging onto more workers than they need. If demand does not soon accelerate, firms will eventually determine that they have too many workers on the payroll and initiate layoffs. That will, in turn, reduce employment, produce the long-awaited recession, and boost the unemployment rate. That is not a pretty picture. But we think the recent productivity drop is overstated and, as a result, the anticipated negative consequences are exaggerated. In our view, the naysayers conveniently overlook the fact that productivity soared following the 2020 recession. The economy plunged into recession in March and April 2020 when the economy shut down. But in subsequent months demand came roaring back far more quickly than anyone expected, firms could not find enough bodies to hire, and productivity soared. Firms were able to boost output significantly even though they could not find as many workers as they desired. In the past couple of years firms have been trying to re-establish a more normal relationship between headcount and output. Headcount has increased steadily with a smaller increase in output. The result has been a decline in productivity for the past two years. Interestingly, if there had been no recession and productivity continued to grow at the same 1.3% pace as in the previous ten years, it would be exactly where it is today. So, do not be faked out by the recent decline in productivity. It does not mean a lot. Like every other economic indicator the data were distorted in one direction during the pandemic, and equally distorted in the opposite direction in the past couple of years. Rest easy.

Productivity simply measures the relationship between output and hours worked. When output grows more quickly than hours worked productivity rises. Workers are working more efficiently. It is an important concept. Our standard of living — also known as the economy’s potential GDP growth rate or our economic speed limit – depends on it. If the economy consistently grows faster than potential, inflation will rise. If productivity growth disappoints all sorts of bad things happen. GDP, inflation, and our standard of income will grow less quickly than desired. Corporate profits and the stock market will struggle.

Over the long haul, potential growth is determined by adding the long-term growth rate in the labor force to the long-term growth rate of productivity. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that over the next decade potential growth will grow 1.8% — 0.4% growth in the labor force combined with 1.4% growth in productivity. The relationship between productivity growth and the economy are easy to figure out in a theoretical sense. But measuring productivity accurately is another story.

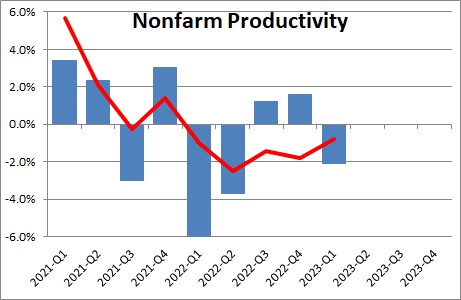

Productivity growth is extremely volatile from quarter to quarter as evidenced by the blue bars in the chart below. To smooth out some of these quarterly wiggles economists will focus more closely on the year-over-year growth rate – the red line. The year-over-year growth rate has declined for the past five consecutive quarters. That has set off alarm bells. But, in our view, it is not painting an accurate picture of what is going on.

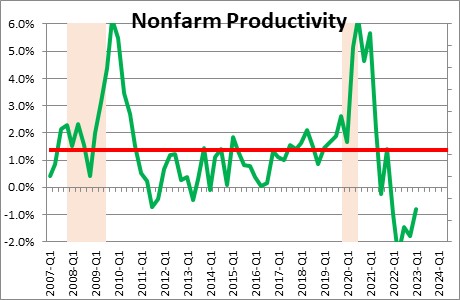

If one takes a somewhat longer-term view productivity growth does not appear quite so troublesome. The chart below shows the year-over-year growth rate for productivity going back to 2007. Thus, it includes its behavior during and after two recessions. Productivity tends to climb sharply when the economy initially climbs out of recession, but then grows far more slowly in the years beyond – but it still grows. But in the past couple of years productivity has not grown slowly in those subsequent years, it has actually declined. This seems different from its usual post-recession behavior and it has raised warning flags amongst the economics profession.

But every economic indicator has been significantly distorted in the past few years. Prime examples are GDP growth and employment, both of which plunged during the recession and subsequently came roaring back. Productivity growth is no different except for the fact that the distortion went in the opposite direction – it first soared and has subsequently fallen. But pretend that the recession never happened. If one looks at the level of productivity that existed just prior to the recession, and assumes that it continued to grow at the same 1.3% pace that it did in the previous 10-year period, its level today would be exactly what one would expect. Yes, productivity growth has fallen for almost two years, but one cannot ignore the fact that it soared in the immediate aftermath of the 2020 recession. Its growth rate in the past three years – 1.3%– is identical to its long-term average growth rate. Thus, we believe that the focus on its recent behavior is misleading.

Having said that, the growth distortions should have largely washed out by now and productivity growth should soon return to its longer-term growth rate of 1.3% — or perhaps even faster. Artificial intelligence holds the promise of boosting the long-term growth rate of productivity significantly. That is an enticing prospect. Should we dare to think potential growth could eventually climb to 2.5%?

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me