March 1, 2024

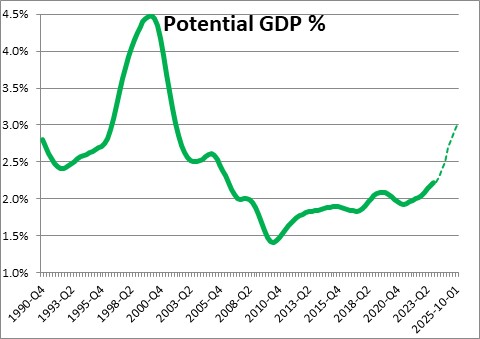

The Congressional Budget Office currently estimates potential GDP growth in the U.S. for the next decade to be 2.0% — 0.6% growth in the labor force plus 1.4% growth in productivity. Potential GDP growth can be thought of as the economy’s speed limit. If the economy is at full employment the economy cannot grow at a rate in excess of potential for a protracted period of time without giving rise to inflation. But a curious thing has been happening. In the past year the economy has been at full employment, yet GDP growth has averaged 3.0% while the core inflation rate has slowed from 5.7% to 3.9%. That is not supposed to be happening. What gives? Our sense is that the economy is benefitting from considerable investment in technology which has boosted productivity considerably. And with additional benefits from AI coming soon, it is possible that the economy can now grow at a sustained 3.0% pace without triggering an uptick in inflation. For example, if the economy grows at a 2.0% pace this year and potential growth is 3.0%, the inflation rate should continue to decline which will allow the Fed to begin lowering rates by mid-summer. Second, keep in mind that potential growth is a proxy for growth in our standard of living — 3.0% is clearly far better than 2.0%. Finally, faster growth in productivity enhances corporate earnings as firms produce more output without having to hire more workers. Sound whacky? Consider the following:

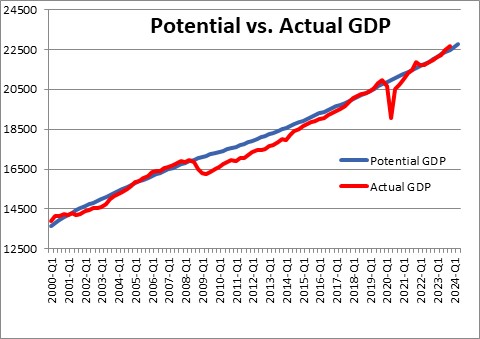

The Congressional Budget Office estimates the economy’s potential growth rate which is, effectively, the economic speed limit. It is currently projected to be 2.0%. That growth rate represents the sum of growth in the labor force (0.6%) plus growth in productivity (1.4%). During a recession the actual level of GDP falls below its potential growth path. The economy develops considerable slack as the unemployment rate rises and the capacity utilization rate declines. Once the economy begins to recover it can grow quickly for a while because there are so many unemployed workers and so much idle capacity. But eventually it returns to full employment. If the economy continues to expand at a rate well in excess of potential, the excessive demand will begin to boost the inflation rate. That is the theory, but that has not been happening recently. Why?

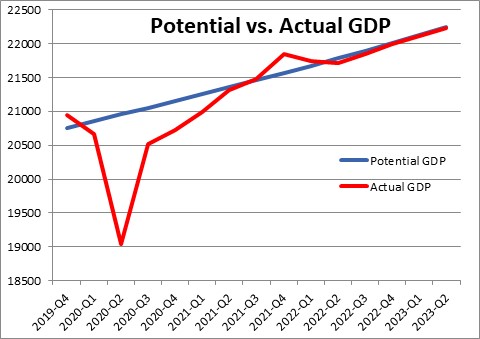

When COVID hit in 2020 our leaders in Washington implemented a quarantine. The economy collapsed and the level of GDP fell far below its potential path. The unemployment rate soared to 14.9% by April of that year. Capacity utilization fell from 77% to 62%. Lots of unemployed workers and idle capacity. But then the economy surged in the second, third, and fourth quarters of 2020, and the first quarter of 2021. The level of GDP returned to its full employment level by mid-2021. Continuing rapid GDP growth in the second half of 2021 pushed actual GDP growth far above its potential growth path and we know the end of that story. The inflation rate soared.

Since then GDP growth has moderated and the CBO believes that actual and potential growth have been tracking along essentially the same path since the middle of 2022. But if the economy is truly at full employment and GDP growth is 3.0%, how can the core inflation rate slow from 5.7% to 3.9%. We are going to suggest that productivity growth may have quickened from the CBO expected growth rate of 1.4% to 2.5% or so.

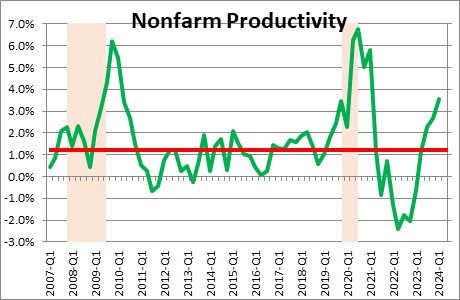

Over the past 15 years productivity growth has averaged 1.2%. The CBO’s estimate of 1.4% is roughly in line with history.

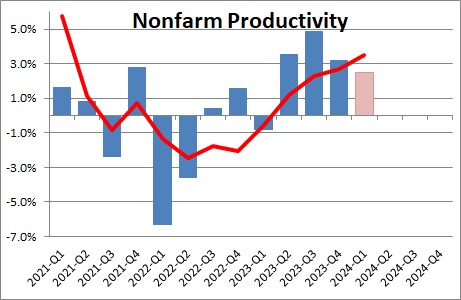

In the second, third, and fourth quarters of last year productivity grew at annual rates of 3.6%, 4.9%, and 3.2%. We do not yet know what it will be in the first quarter but we can guess. Currently the widely followed Atlanta Fed GDPNow series pegs GDP growth this quarter at 2.1%. The combination of payroll employment and the nonfarm workweek suggest that hours worked are likely to rise 0.7%. The implication is that first quarter productivity growth could be the difference between those two numbers or 1.4%. If so, then in the past four quarters productivity growth has climbed to 3.2%. Is this a blip? Or is it the beginning of an extended period of rapid productivity growth? We suggest it is the latter.

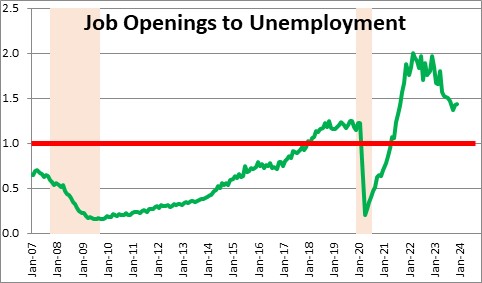

We believe that the recent surge in productivity reflects rapid growth in tech spending in 2021 and 2022. Our theory is that by mid-2021 the unemployment rate was very low and job openings far outpaced the number of unemployed workers. In fact, there were almost 2.0 job openings for every unemployed worker. That is not normal. Over the past 15 years the ratio of job openings to unemployed workers has averaged 0.6. What that means is that there are typically fewer job openings than there are unemployed workers. But that has not been the case since the spring of 2021. Since then the labor market has been red hot with, at its peak, almost 2.0 jobs available for every unemployed worker.

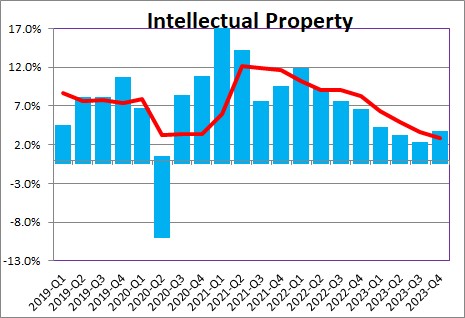

If business people cannot find the number of bodies that they need, what do they do? We believe they turn to technology in an effort to boost productivity. They may not be able to hire more workers, but if they spend some money on technology they make be able to make each of their existing workers more efficient. In fact, tech spending rose at roughly a 10% pace annually for almost two years. The end result is that, with an appropriate lag, productivity growth has surged. Such spending has slowed in this past year but the Fed was raising rates rapidly and almost every economist on the face of the planet expected a recession. Not surprisingly, tech spending slowed. But with a recession now out of the picture and the Fed poised to begin lowering rates by midyear, tech spending seems poised to rebound in 2024. Add to that the fact that AI is being adopted at a rapid and accelerating pace and it seems likely that productivity growth should remain elevated.

So what does this mean for the economy’s speed limit. First, as noted earlier, the CBO’s 2.0% potential growth rate estimate consists of 0.6% growth in the labor force plus 1.4% growth in productivity. But if productivity growth has climbed to 2.5% for the foreseeable future, then potential growth could have climbed, or be in the process of climbing to, say. 3.1% (0.6% + 2.5%).

Second, potential GDP is a proxy for the growth rate in our standard of living — 3.1% is clearly far better than 2.0%.

Third, more rapid growth in productivity implies improved corporate earnings — more output with fewer workers. Perhaps the various stock market indexes are not as overvalued as most economists and stock market gurus seem to think.

Technology and AI may be a game changer.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me