November 3, 2017

After being stagnant for a couple of years productivity is finally on the rise. We expect its recent pace to be sustained in 2018 which causes lots of good things to happen. The economy’s economic speed limit will accelerate from 1.8% today to 2.8% or so in the years ahead. Faster growth in productivity will boost wages to about 3.5%. Faster income growth will raise the standard of living by 1.6%. Finally, faster productivity growth will keep inflation in check. Consider the following:

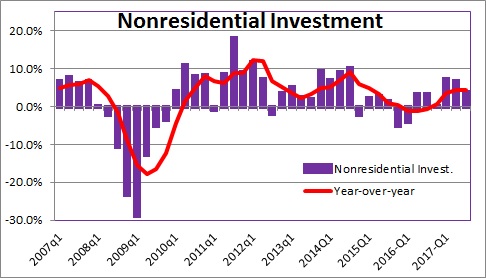

Productivity growth is closely tied to investment. Give workers the latest technology or upgraded equipment on the factory floor, the same number of workers will be able to produce more output. Investment spending was essentially unchanged in 2015 and 2016 as falling oil prices crushed investment in the oil sector and business leaders were frustrated by the gridlock in Congress.

But following Trump’s election things began to change. In the month after the election many large companies vowed to create jobs in the U.S. Amazon said it intends to add 100,000 new jobs, Walmart — 10,000, Sprint – 50,000, Pizza Hut – 11,000, and Chinese retail giant Alibaba says it will create one million new jobs in the U.S.

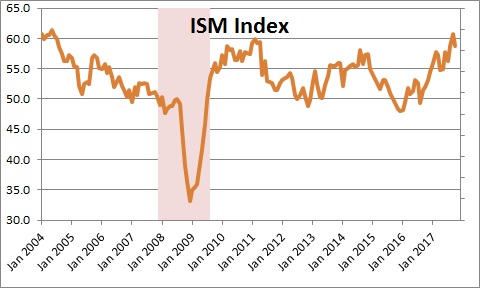

Then, corporate leaders became about excited about the possibility of a cut in the corporate tax rate, repatriation of overseas earnings to the U.S. at a favorable tax rate, and a significant reduction in the particularly onerous regulatory environment. As a result, corporate confidence has soared. The Institute for Supply Management’s (ISM) survey of conditions in the manufacturing sector reached its highest level since 2004. The ISM survey for non-manufacturing firms looks similar. Small business confidence has soared to its highest level since 2004. Big firms, small firms, manufacturers, and non-manufacturing firms are all bursting with confidence.

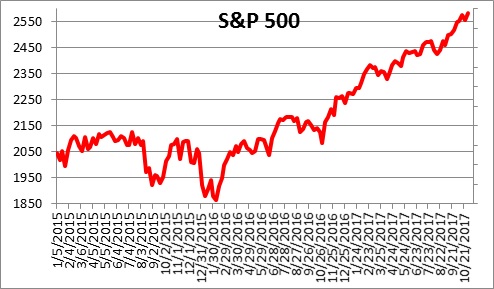

Meanwhile the U.S. stock market has surged to a series of record high levels. It has climbed more than 20% in the past year. Stocks around the globe are climbing at an equally brisk pace.

Against this background, corporate leaders have begun to open their wallets. After essentially no growth for three years, investment spending surged by 7.2%, 6.7%, and 3.9% in the first three quarters of this year. If the corporate tax cuts and repatriation of earnings come to pass, investment spending will climb for years to come. We anticipate a 5.0% increase in investment spending in 2018.

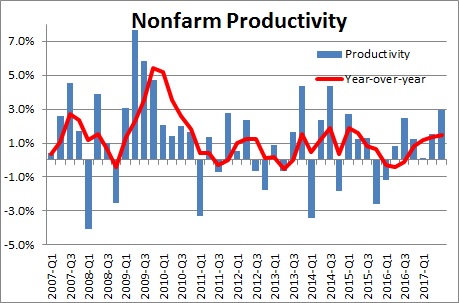

The ratcheting upwards of investment has caused productivity to rebound. Following a couple of years with growth that averaged 1.0%, productivity rose 1.5% in the second quarter and 3.0% in the third (which happens to be the biggest single-quarter advance in three years). Something different seems to be happening.

Faster growth in productivity causes lots of good things happen. First, our economic speed limit accelerates. That speed limit can be estimated as the sum of growth in the labor force plus productivity growth. Currently the labor force is climbing by a reduced 0.8% pace as the baby boomers continue to retire. Productivity is currently climbing at about a 1.0% pace. Add those two numbers and it becomes clear that the economy’s speed limit today is an anemic 1.8%. But suppose that the additional investment spending boosts productivity growth from 1.0% to 2.0%. Now suddenly the sum of 0.8% growth in the labor force and 2.0% growth in productivity boosts that economic speed limit to 2.8%. Trump believes his tax cuts will boost GDP growth to 3.0%. He may not be too far off the mark.

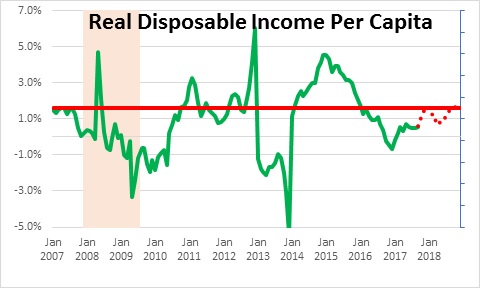

Faster growth in the economy means that income will be growing more quickly. Specifically, 1% faster GDP growth means 1.0% additional growth in income. The most widely used measure of our standard of living is the growth rate of real, after tax, income per capita. It is currently rising by 0.6% annually. Tack on an additional 1.0% growth in income and suddenly it climbs to 1.6% which is close to its long-term growth rate.

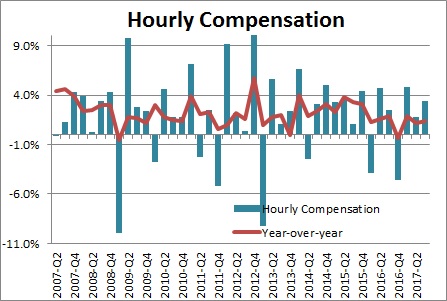

If productivity grows more quickly compensation will also accelerate because workers have earned their fatter paychecks. If employers boost worker compensation by 3.0% one might think that labor costs increase by 3.0%. But what if workers are 3.0% more productive and the firm gets 3.0% more output? The firm does not care. Its workers have earned those higher wages. In the last year compensation rose 1.4%, but in recent quarters growth has picked up. We expect compensation to increase 3.5% in 2018.

Won’t the faster 3.5% growth rate in compensation lead to higher inflation? Not really because of the pickup in productivity. We expect compensation to increase 3.5% next year, but we also expect productivity to rise by 2.0%. Thus, the increase in labor costs adjusted for the increase in productivity is 1.5%. Economists have a name for this concept and that is “unit labor costs”. This is the best measure of the upward pressure on inflation caused by rising labor costs. An increase in unit labor costs of 1.5% is perfectly consistent with the Fed’s 2.0% inflation target.

Thus, in coming years we expect GDP growth to match its potential growth rate of 2.8%. That allows worker compensation to grow more quickly and raises our standard of living, but it is not inflationary because of the largely offsetting increase in productivity (2.0%).

As we see it such a scenario could extend the expansion well beyond 2020. We have often said that the Fed will raise the funds rate to a “neutral” rate of 3.0% by mid-2020. But with the economy expanding at a rate in line with – but not exceeding – its potential growth rate, and inflation steady at the 2.0% mark, it will have no incentive to push rates any higher. In the past the Fed has needed to raise the funds rate about 2.0% above the “neutral” to trigger a recession – or in this case about 5.0%.

Given this environment, there is no reason to think that this expansion will end in 2020. It could go well beyond that date. 2022? 2025? Sounds crazy, but is it?

Stephen D. Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me