October 16, 2015

Some economists fear that even without the Fed’s help interest rates could inadvertently short circuit the expansion. This could happen in one of two ways. First, the Fed surprises the markets by raising rates unexpectedly and long-term interest rates rise enough to abort the expansion. Second, by holding short-term interest rates at 0% for so long, the Fed is encouraging investors to seek risky assets such as the stock market, junk bonds, and emerging markets which, if they suddenly turn downwards, could prematurely terminate the expansion. There is scant evidence to substantiate any such fear.

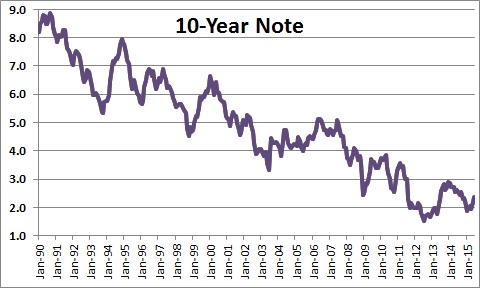

It is true that if the Fed surprises the markets and raises rates at a time when it is not expected to do so, long-term interest rates will rise. This was the case when Bernanke spooked the market in June 2013 by suggesting that the Fed would slow its pace of bond buying later that year. The yield on the Treasury’s 10-year quickly jumped from 1.5% to almost 3.0%. But then what happened? As the Fed reassured markets that this was not a “tightening” move but, rather, a “slightly slower pace of easing”, rates gradually declined back to the 2.0% mark. This event became widely dubbed the “taper tantrum”. While that move was a surprise, this initial rate hike by the Fed has been widely discussed for a year. While the markets may not like it – whenever the Fed chooses to do so – there is unlikely to be a severe negative reaction. And once the Fed reassures us that it intends to proceed very slowly thereafter, the initial selloff should be largely offset.

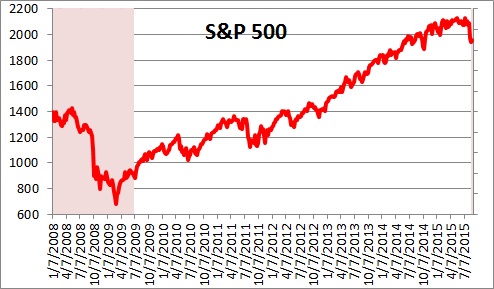

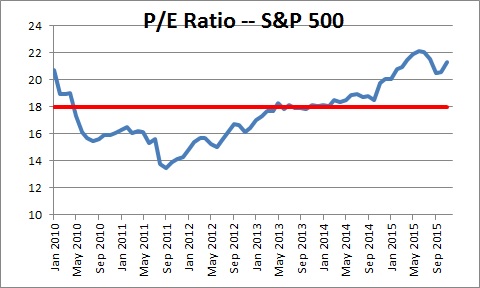

The argument that extremely low interest rates will encourage investors to seek out risky assets is intellectually appealing, but that is not happening. The stock market recently experienced a 10% correction and has since recovered about one-half of its previous loss.

The correction was triggered by stock prices increasing a bit faster than earnings so that the price/earnings ratios that stock analysts examine got a bit out of line with its historical average. Could stock prices still be a bit on the high side? Perhaps, but not significantly so.

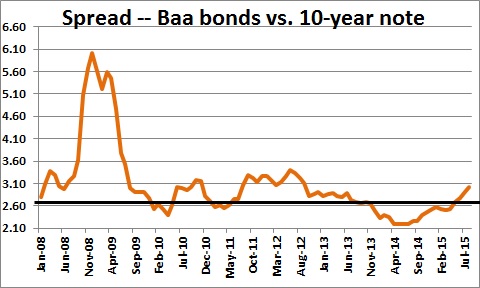

Could investors be seeking the returns offered by higher yielding corporate assets? Not really. The Fed publishes a series on Baa bonds which are higher risk, but still investment grade assets. During the recession when investors were really scared, they sold any sort of risky asset which pushed up the yield and the spread. During the good times they buy these assets and the spread drops back in line with its historical norm which is about 2.6% above the yield on the Treasury’s 10-year note. One could have made a stronger case that investors were reaching for yield at about this time last year when spreads shrunk to 2.1%. But with the drop in gas prices and slower growth in China, investors have become jittery and spreads have widened by about a percentage point to 3.1%. Thus, investors in the bond market do not appear to be taking on any undue amount of risk.

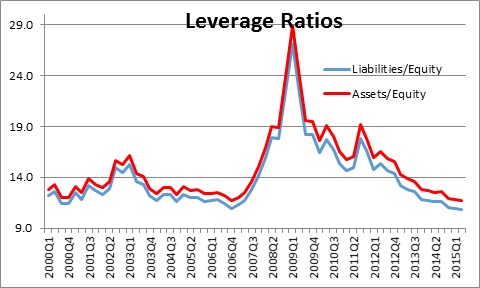

What about banks? Could they be trying to increase their return by making riskier loans? Once again the answer is no. Under pressure from regulators banks have been steadily boosting equity since the recession ended in mid-2009 and, as a result, leverage ratios such as total assets or total liabilities to equity are the lowest they have been in a decade.

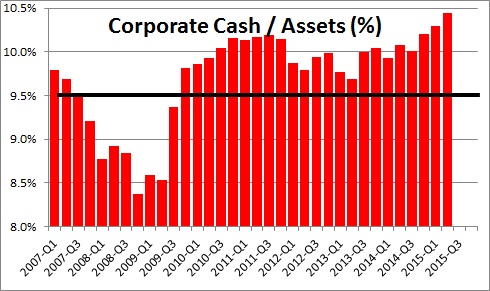

Corporations are choosing to sit on a mountain of cash. They had serious cash flow problems during and shortly after the recession and clearly do not want to repeat that experience. Because most of this cash is invested in assets that earn essentially 0% one could argue that, if anything, corporate leaders are being unduly cautious.

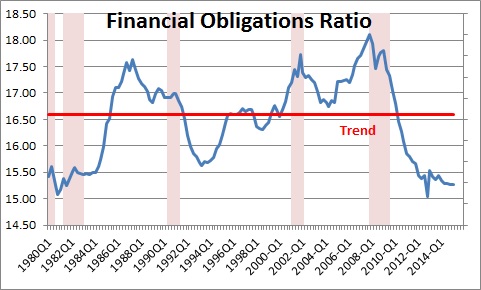

Finally, consumers have paid down huge amounts of debt in the six years since the recession ended. In their case debt in relation to income is the lowest in 30 years which is in sharp contrast to what it was just prior to the recession. At that time the consumer was very highly leveraged.

While it seems logical that when short-term interest rates are essentially at 0% that consumers, corporations, bankers, and investors might be tempted to take on risk in an attempt to boost their profits and return, but that simply does not seem to be happening. We would argue perhaps the opposite, that all of those groups are acting a bit too cautiously.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Steve, It is always good you read your clear, no-nonsense perspective on the economy. I just read another perspective which stated that the stock market is in the “Twilight Zone” or “secular stagnation” even though the economy is experiencing slow, steady growth. Maybe the 3% goal for growth is just a bit too much. Maybe 2%+/- makes more sense. What is you thinking on that situation?

Keep up the excellent work. …Darrel