February 10, 2023

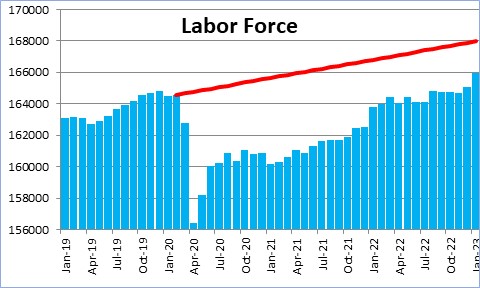

One of the many economic mysteries since the economy dipped into recession in March 2020 is, where did all the workers go? The labor force at the beginning of the recession was 164.5 million workers. This represents the number of people who were either employed or actively seeking employment. Like all economic indicators the labor forced plunged during the recession. It finally re-attained its pre-recession level in November. But the labor force is supposed to grow roughly in line with the population. If it had done so in the past three years the labor force would be about 2.5 million workers bigger today than it is. It appears that perhaps 1.0 million of those workers retired and 0.5 million died from COVID. The other 1.0 million workers left the labor force for reasons that are unclear. But suddenly in December and January the labor force rose by 1.3 million workers. Could it be that some of those folks who left the labor force are now actually looking for jobs? We think so. If that is the case it changes the entire economic outlook for 2023. More jobs mean more people are earning a steady income and with additional growth in earnings, consumers have more spending power. Given that these additional labor force participants are finding employment, more jobs means that the unemployment rate may not rise much between now and yearend. GDP growth for the year may not be the 1.0% that had been generally expected, but something faster. A continuing tight labor market will maintain upward pressure on wages which will, in turn, make it more difficult for inflation to return to the Fed’s 2.0% target. It may be premature, but the soft landing scenario of slow growth combined with lower inflation that most economists had envisioned for 2023 may be totally off the mark, replaced by faster growth, little decline in the inflation rate, and higher interest rates.

If the labor force is 2.5 million workers short of where it ought to be, what happened to them? It appears that about 1.0 million or so retired and another 0.5 million died from COVID. The reasons for the remaining 1.0 million workers not returning to work are less clear.

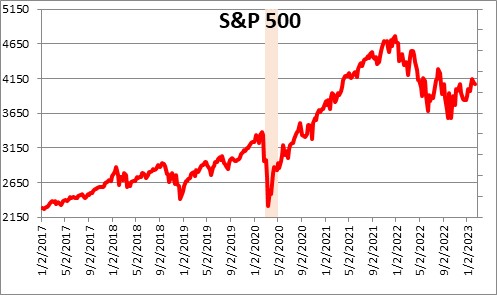

But in December and January the labor force jumped by 1.3 million workers and all of them found jobs as the unemployment rate fell 0.2% to 3.4%. Our sense is that the expectation of a deteriorating economic environment may have changed some of those missing workers opinion about employment. Of the estimated 1.0 million workers who retired, at the time of their retirement the stock market was soaring. But in the past year the stock market has fallen 15%.

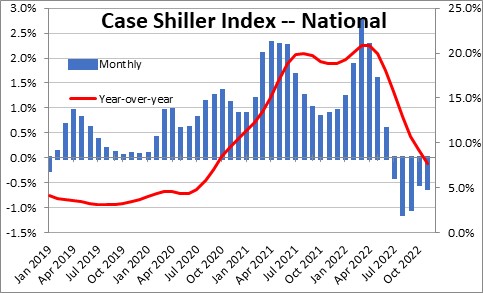

At the same time, home prices had been rising 1.0-1.5% per month for two years which resulted in 20% gains in a year. But now, the value of their home has begun to fall and is likely to continue declining by 0.5-1.0% per month. As a result, those year-over-year increases have been shaved from 20% to 6%, which will be replaced by year-over-declines within a couple of months.

Meanwhile, most economists are expecting a recession at some point in 2023. If that happens, monthly job gains will turn into declines and finding a job will be more challenging. Perhaps better to seek employment now than wait.

Against that background, it is possible that some of those early retirees may do a re-think and are now questioning whether they have enough money to last through the end of their lifetime. If the answer to that question is ” no”, the allure of a steady job could entice them back into the labor market.

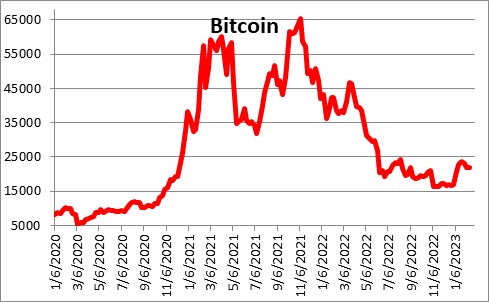

In addition to retiring or dying, when economic times were booming a year ago some labor force participants may have given up their day job and begun to trade Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. When they stop looking for a job they fall out of the labor force. But the demise of FTX, Genesis, and others has undoubtedly bankrupt some of these day traders who now need steady employment.

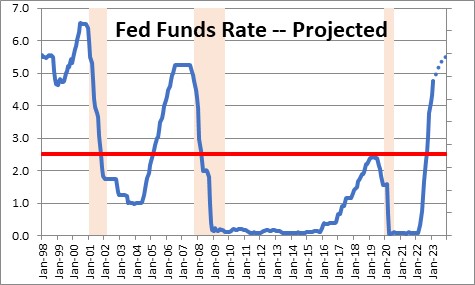

If more workers re-enter the labor force the monthly employment gains between now and yearend will be substantial. We are expecting payroll employment to rise by 205 thousand per month compared to monthly gains of 356 thousand in the most recent three-month period — substantially slower, but still positive. With employment gains of that magnitude going forward the current 3.4% unemployment rate may only rise slightly between now and yearend to perhaps 3.8%. The Fed believes it needs to create some slack in the labor market (i.e., pushing the unemployment rate higher to perhaps 4.5%) to alleviate the wage pressures that are preventing the inflation rate from falling more quickly. If that is the path for the labor market going forward, the Fed is not going to have the ability to lower rates between now and yearend – which is exactly what Fed Chair Powell and other Fed officials have been telling us.

With more sizable employment gains GDP growth is likely to be faster than expected. Prior to the employment report most economists expected first quarter GDP growth of 0.5%. Now it is about 2.0%. The widely expected growth slowdown keeps getting pushed farther and farther down the road. The expected slowdown later in the year may, or may not, materialize.

If most of the missing workers find a job between now and yearend the GDP growth, inflation, and interest rate outlook for 2023 will be very different.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me