October 5, 2018

The combination of strong economic news and a 48-year low in the unemployment rate this past week spooked the bond market and pushed bond yields to their highest level in seven years. The speed of ascent in bond rates created jitters in the stock market which quickly retreated from a record high level. The theory is that steady tightening in the labor market will induce the Fed to raise rates more quickly than anticipated and potentially jeopardize the near-record length expansion. This is the latest in a never-ending string of market fears which we do not share. It is abundantly clear that the Fed will continue to raise short-term interest rates for at least another year. It has told us what it intends to do. Bond yields will also continue to climb. However, the level of both short- and long-term interest rates will not negatively impact the economy for at least another three years. Here is why.

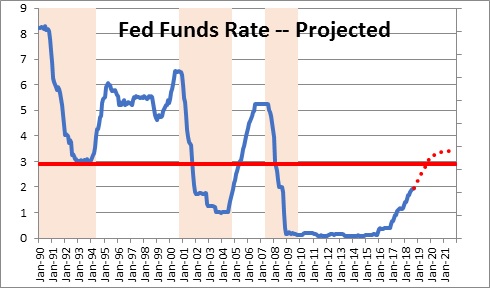

The Fed recently raised the funds rate to 2.0-2.25%. However, it believes that its policy stance is “neutral” when the funds rate is about 3.0%. At its latest FOMC gathering on September 25-26 it outlined its expected rate of funds rate hikes through 2021. It intends to raise the funds rate one more time this year (presumably in December), three times in 2019, and one final time in 2020. That would lift the funds rate to 3.4%. But that is as far as it intends to go. Short rates will be steady in 2021. It is important to recognize that the U.S. economy has never gone into recession until the funds rate has risen to at least the 5.0% mark. Thus, Fed policy should not jeopardize the expansion for at least another three years.

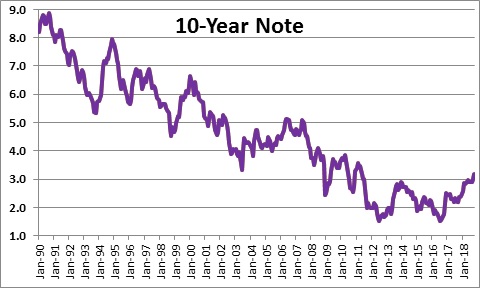

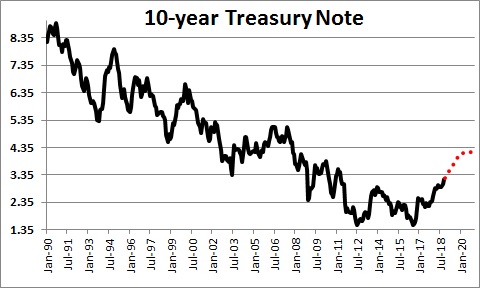

The strong economic data and 3.7% unemployment rate caused bond yields to jump to 3.2%. That is the highest level of long-term interest rates since 2011. However, a 3.2% bond yield is still very low relative if one uses a somewhat longer time horizon. Prior to the 2007-08 recession bond yields were consistently in a range from 4.0-9.0%.

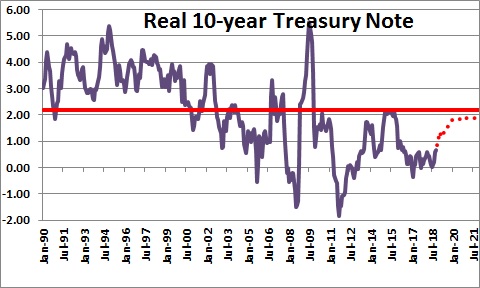

To determine whether long-term interest rates are “high”, it is helpful to look at long-term interest rates in relation to inflation, which is known as the “real” rate. In the period since 1990 the “real” 10-year rate has averaged 2.2% which means that the 10-year yield tends to be 2.2% higher than the inflation rate. With the 10-year currently at 3.2% and the year-over-year increase in the CPI at 2.4%, the “real” rate today is 0.8%. It is much lower than the 2.2% one would expect given this historical relationship. Why is that?

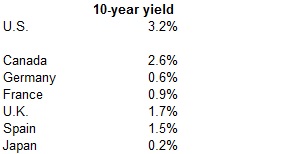

We would suggest that the robust pace of economic expansion in the U.S., an expected steady diet of additional Fed tightening, and a gradual increase in the inflation rate have pushed long-term interest rates in the U.S. to the 3.2% mark which is far higher than bond yields available elsewhere around the globe. As a result, foreign investors have been flocking into the U.S. 10-year and thereby compressing the real rate relatively to history.

Over the course of the next couple of years we expect the CPI to average 2.4%. At the same time, we expect the “real” rate to climb from 0.8% to 1.8% which is close to its long-term average. That would put the 10-year note yield at 4.2% by the end of 2021.

For that to happen the Fed needs to keep inflation expectations in check. That means it cannot afford to back away from the planned trajectory of rate hikes over the next couple of years. Right now, inflation expectations (as measured by the 10-year note rate less the “inflation adjusted 10-year note) have been steady at 2.1% for the past year.

As we see it, both short- and longer-term interest rate levels are going higher with most of the run-up occurring by the end of next year. The funds rate should climb to 3.4% which is slightly higher than its “neutral” rate of about 3.0% but still well below the 5.0% level that was required to tip the economy over the edge in previous cycles. The yield on the 10-year note should climb from 3.2% today to 4.2%. But that means that the “real” 10-year rate would be 1.8% which is still lower than its long-term average. Hence, neither short- nor long-term interest rates are likely to rise to levels that could endanger the expansion for at least another three years.

Is this scenario too good to be true? Perhaps. There are always risks and this period is no different. But Fed Chairman Powell said in a speech last week that Fed economists, as well as several private sector forecasters, have come to the view that the recent period of strong growth, low unemployment, and relatively stable inflation can continue for some time to come. We agree.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me