May 9, 2014

Some people have expressed concern about recent increases in food and energy prices. They claim that the only reason the inflation rate is well-behaved is because economists routinely exclude food and energy prices from their analysis. Economists do exclude food and energy prices, but they do so for a reason. Here’s why. Furthermore, we believe you should not be unduly concerned about the recent run-up.

Economists are always trying to determine changes in the inflation rate. If inflation begins to climb the Federal Reserve will be forced to respond by raising interest rates to slow the economy and cool inflation. But often the consumer price index can rise because of a substantial increase in food or energy prices. If those prices rise for a couple of months and subsequently decline, it is of little consequence and not indicative of a troublesome change in the underlying inflation rate. However, if those prices increases are more sustained they could seep into the prices of other products and contribute to a more general increase in inflation. That is a problem. So what is happening today?

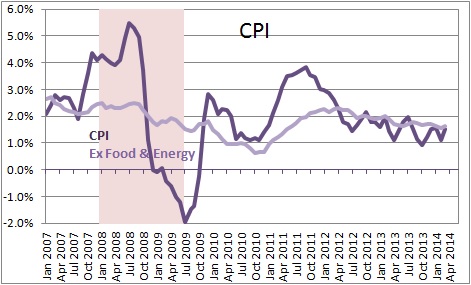

The CPI excluding the volatile food and energy components has been risen 1.6% pace in the past year. The overall CPI – including food and energy prices — has risen 1.5%. But in February and March food and gasoline prices began to rise and some fear the beginning of a pickup in the inflation rate. We believe that the inflation outlook remains benign.

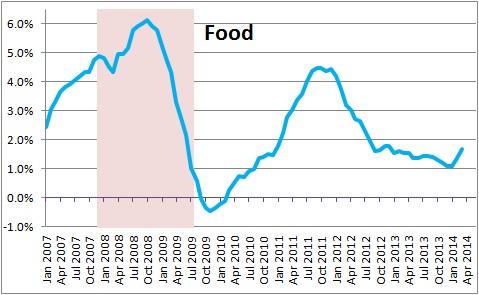

Food prices are notoriously volatile. They rise and fall. When they climb they attract some rather vocal concern. As shown below food prices have had several decisive swings in the past six years. They rose sharply in 2008 then declined. They surged again in the second half of 2010 only to decline once more. More recently they have been fairly steady in a range from 1.0-1.5%.

Drought conditions throughout much of the West and the South last summer have finally begun to push food prices upwards. In both February and March food prices rose 0.4%. Will they rise further?

Occasionally weather conditions eliminate much of one crop. And sometimes farmers have to bring their cattle or hogs to market sooner than they otherwise would because it costs too much to feed them. That ultimately pushes meat prices higher. But eventually new crops are harvested and the herds are restored. At that time food prices fall almost as rapidly as they had risen. While food prices may climb for several more months, by mid- to late summer they should begin to change direction.

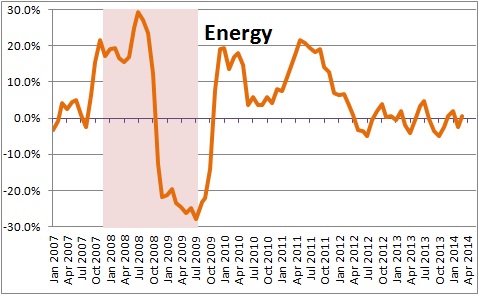

Energy prices are also notoriously volatile as seasonal demand ebbs and flows or as international tensions threaten to interrupt the flow of oil. As shown below, price changes of 30% occur with a great deal of regularity. Recently price changes have been much more subdued. In fact, in the past year the energy component has risen by 0.6%.

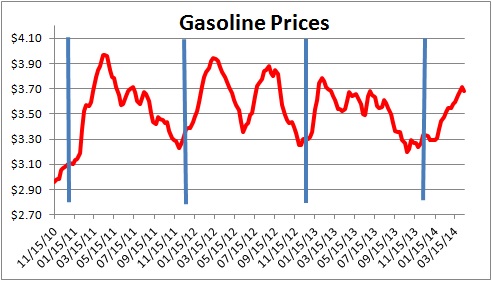

But from mid-February through late April gasoline pump prices rose steadily from $3.29 per gallon to $3.71. But gasoline prices always seem to rise in the first few months of a year and 2014 is no exception. The blue vertical lines below are drawn at the beginning of each year from 2011 to 2014. Gasoline prices always rise early in every year presumably in advance of the summer driving season. But by mid-summer they head the other direction as demand abates. The recent run-up in gasoline prices is probably nothing more than the normal early year increase that will be reversed by summer.

When food and/or gasoline prices rise people become concerned. We all have to eat. We all have to fill the car with gas. But it is also important to put things into perspective and recognize that food and energy prices are notoriously volatile and while they may be rising today they frequently head in the opposite direction tomorrow. In this particular instance the rising prices have been of relatively short duration. Jumping to the conclusion that the inflation outlook is deteriorating is almost certainly premature. This short-term volatility in food and energy prices is exactly why economists exclude them from their analysis.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me