October 4, 2024

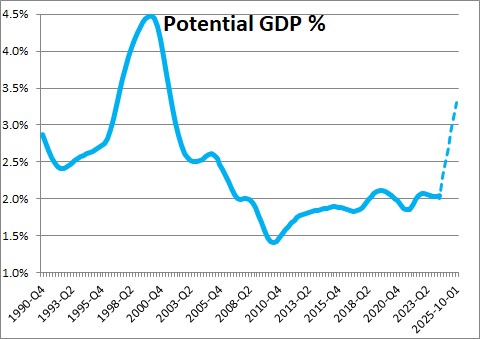

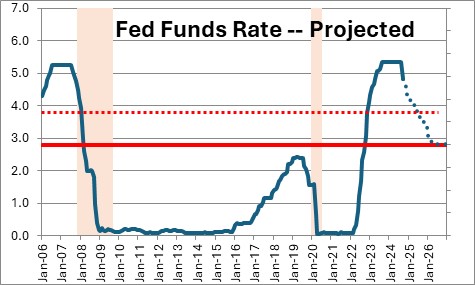

Every time economists conclude that the long-awaited slowdown is at hand they get slammed. This time it was by the strong employment report for September. Payroll employment for that month rose 254 thousand which was far bigger than even the most optimistic economist expected. The unemployment rate declined 0.1% to 4.1% which is below the Fed’s estimate of full employment. Following GDP growth of 3.0% in the past year the third quarter GDP growth rate appears to be about 2.5%. So where, exactly, is the growth slowdown that everybody keeps expecting? Where, exactly, is the weakness in the labor market that the Fed seems to fear? We would suggest that productivity gains have boosted the economy’s potential growth rate from 1.8% to the 3.2% mark. In other words, a 3.2% GDP growth rate is no longer an excessively rapid growth rate that will trigger an acceleration in inflation. Rather, it is a growth rate that should be welcomed because it will result in faster growth in our standard of living. If the economy can grow far more quickly today than it has in the past, the “neutral” level for the funds rate is no longer 2.8% but perhaps 3.8%. The Fed still appears to have some room to cut the current 4.8% funds rate. But we would suggest that a relatively slow pace of rate cuts is now appropriate. Fed policy is not nearly as far out-of-whack as what the Fed thought when it cut rates in September.

The 254 thousand increase in payroll employment in September fooled everyone. Based on gains in previous months economists expected a gain of about 150 thousand. The strength was not only in September. Employment in July and August were revised upwards by 55 thousand and 17 thousand, respectively. As a result, the average employment increase in the past three months has been 186 thousand.

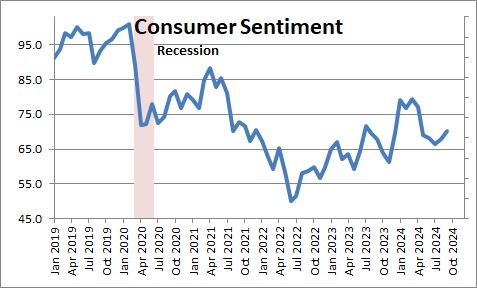

The employment gain was broad-based, but of particular note to us was the increase in the leisure and hospitality category which jumped 78 thousand. At first blush this seems odd. Consumer sentiment remains very low. When consumers are anxious they have historically cut back on spending. But that has not been the case for the past couple of years and it is not starting now. Following the GDP revisions in September, consumers now have sufficient income growth to allow them to spend at their current pace indefinitely.

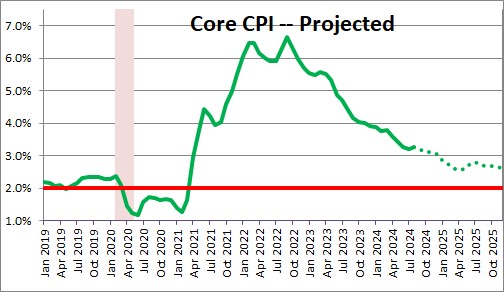

Most economists believe potential GDP growth is 1.8%. But if that is true, then why is it that with GDP growth of 3.0% in the past year the inflation rate has not accelerated? In fact, the core CPI has actually slowed in the past year from 4.4% to 3.8%. This conundrum can be easily explained if the economy’s potential growth rate has risen to the 3.2% mark.

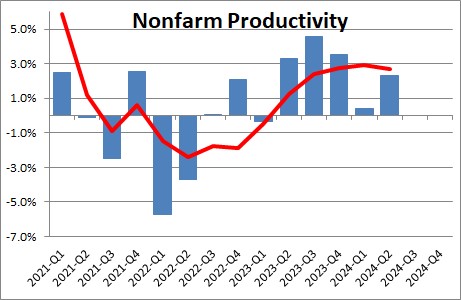

In the past year productivity growth has averaged 2.7%. Compare that to a 1.2% average increase in the decade prior to the recession. We would suggest that this pickup in growth has been caused in part by a scarcity of labor which forced employers to invest in technology to enhance the productivity of existing employees, The rapid deployment of AI is further boosting productivity.

Potential GDP growth is the sum of the growth rate of the labor force plus the growth rate of productivity. In the past year the labor force has risen 0.5%. If productivity growth continues at 2.7%, it is easy to see how potential GDP growth could easily be 3.2%. If that is true, it becomes clear why 3.0% GDP growth in the past year has not been inflationary.

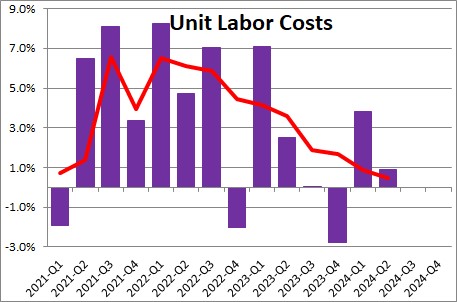

An important part of the inflation outlook is determined by labor costs because two-thirds of a firm’s total cost is labor. But what is important is not the nominal increase in labor costs but unit labor costs. If a firm pays its workers 5.0% more money and they are no more productive, then unit labor cost (or labor costs adjusted for the change in productivity) have risen 5.0%. But what if those workers are 5.0% more productivity. Then, the employer does not care. Workers have earned their 5.0% pay hike and unit labor costs are unchanged. In the past year, compensation has increased 3.0%; productivity has risen 2.7%. As a result, unit labor costs have edged upwards by 0.3%. Strong gains in productivity almost completely offset the runup in compensation. A 0.3% increase in unit labor costs is consistent with an inflation rate well below the Fed’s 2.0% target.

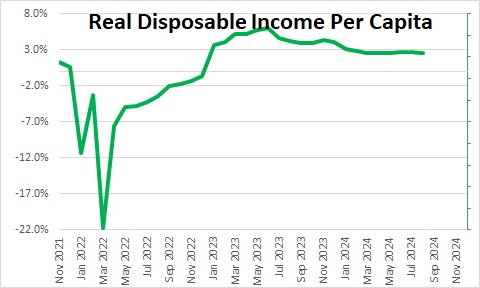

The benefits of a prolonged and pronounced increase in productivity are widespread. The economy can grow much more quickly without giving rise to a pickup in the inflation rate. Furthermore, our standard of living can grow more quickly. In the past year real disposable income per capita – a proxy for our standard of living — has risen 2.6%. In the 10 years prior to the recession it rose 1.7% annually.

Finally, faster potential GDP growth implies that the neutral rate of interest has also risen. Nobody knows exactly what that rate is. It is unobservable and can only be estimated. If previously the Fed thought the neutral funds rate was 2.8%. It is almost certainly higher today. If potential growth has accelerated by 1.0% it makes senses that the neutral funds rate may also have risen by 1.0% to, perhaps, 3.8%. If the funds rate is currently 4.8%, the Fed may not be as far away from a neutral policy stance as it thought previously. Rather than talking about the funds rate falling from 5.5% to 2.8%, perhaps it only needs to drop to 3.8%. That is just four 0.25% rate cuts away.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Steve, it is really hard to read your commentary with the blue numbered background. Please go back to your old format.

Stephen,

How does all of current labor union demands from AT&T, Boeing and ILA figure into the equation?

Thanks for your insight!

Sorry Geoffrey. Had some computer issues last week. My website guru was in Spain. Try it now. It looks OK on my end. Let me know.

Hi Richard,

It is easy to think this is a big deal. But keep in mind that only 10% of the labor force is unionized, and the dockworkers are only a small portion of the total (think about state and local government workers and teachers which are the biggest unions). The settlement certainly seems to be inflationary. More money without any increase in productivity. But its overall impact is likely to be minuscule unless non-union workers somehow think they can soak their employer for more money. That does not seem likely to happen.