September 13, 2019

The European Central Bank provided a surprise dose of monetary stimulus this past week. Not only did it cut interest rates, it announced a new bond-buying program designed to get the economy going. However, policy makers in Europe and the U.S. are beginning to debate the effectiveness of further monetary stimulus. We believe that lower rates in Europe and the United States will not do a lot to boost growth. In our view, policy makers on both sides of the Atlantic should forget about monetary stimulus and focus their attention on inappropriate fiscal policy which is the root of the problem.

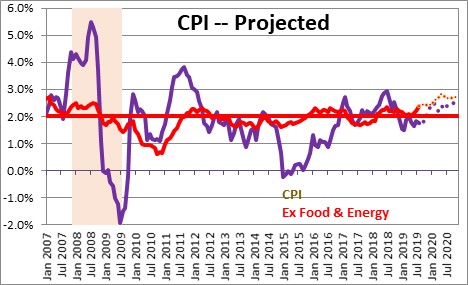

Interest rates in the United States are already very low. If the Fed cuts rates next week the funds rate will be in a range from 1.75-2.0%. But the CPI has risen 1.9% in the past year. That means that the real funds rate is 0.0%.

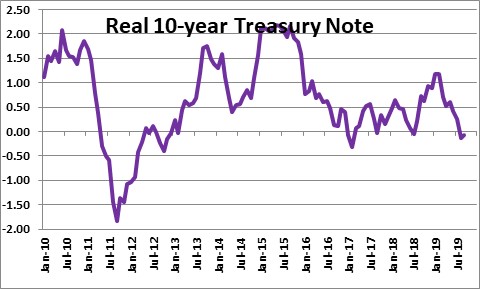

With respect to long rates the yield on the 10-year now stands at 1.9%. The inflation rate is 1.9%. This means that real, long-term interest rates are also 0.0%. Think about that for a minute. The real cost of borrowing for the U.S. Treasury is zero. It can borrow at 1.9% and pay it back with deflated dollars. The idea that interest rates in the United States are too high and thereby impeding GDP growth is absurd.

So why is the Fed cutting rates? Given the lack of evidence that the U.S. economy has softened in any meaningful way, we believe the Fed has been swayed by Trump’s relentless badgering. A few weeks ago Trump said that he wanted the Fed to cut rates by 1.0%. This week he upped the ante and said that rates should be 0% or even negative. He called Fed Chair Powell and his colleagues “Boneheads”. In the past 50 years the Fed has shrugged off Presidential pressure, but this level of vitriol is unprecedented and, apparently, the Fed chose to bend and lowered rates by 0.25% at the end of July and plans another 0.25% cut again next week. But none of this will satisfy Trump.

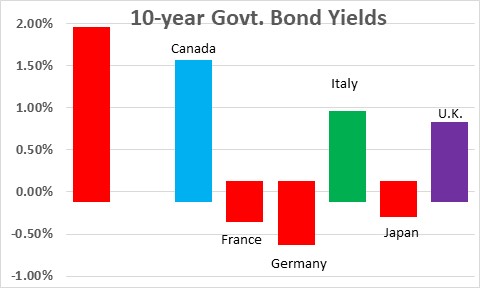

The Fed has attempted to justify its action by suggesting that the tariff war with China and weak growth overseas could slow the U.S. economy later this year or in 2020. Maybe. To us that argument seems a bit contrived and not very likely. However, the Fed may be looking at interest rate levels around the globe and be worried that lower rates elsewhere – like this week’s rate cut by the ECB – without a commensurate drop in U.S. rates will strengthen the dollar and curtail growth in U.S. exports. We do not buy that argument. The 10-year yield in the U.S. is 1.9%. Compare that to bond yields in the other G-7 countries. Long rates are negative in France, Germany, and Japan. They are positive, but significantly lower than the U.S., in Canada, Italy, and the U.K. Global investors have been, and will continue to seek, the higher bond yields available in the United States.

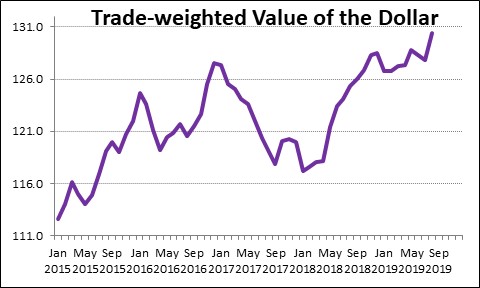

The dollar jumped sharply in August as recession fears spread. Why? Investors concluded that the U.S. was best positioned to weather a global slowdown. As a result, foreign funds flowed into the U.S. and the S&P 500 climbed to a record high level. At the same time, foreign investors seek the still relatively high level of U.S. interest rates. None of that is going to change any time soon. The dollar is likely to continue its gradual ascent which will exacerbate the difference between the moderate pace of GDP growth in the U.S. and notably sluggish performance elsewhere.

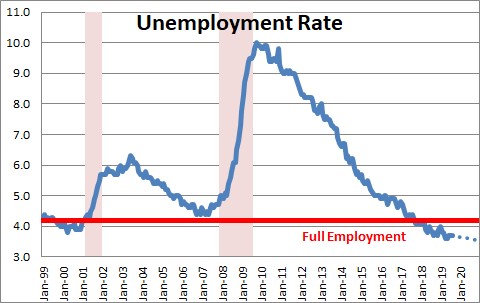

Given that the Fed will cut rates by at least 0.5% this year, will it boost growth? Probably not by much. The economy is already at full employment. To accelerate growth firms need to hire additional workers. But that is probably not going to happen. The unemployment rate is at a 50-year low and there is already a shortage of available workers. Everybody who wants a job already has one. As an alternative, firms could spend money on technology and give their workers on the factory floor the most up-to-date equipment available or purchase the latest and greatest software. Some of that may occur, but Trump’s frenetic trade policy appears to have put a damper on business confidence so any upswing in GDP growth caused by lower interest rates is likely to be modest.

If lower rates entice consumers to spend more but firms cannot increase production, they might respond by raising prices. That already seems to be happening. The core CPI has begun to accelerate. It rose 1.8% in 2017, 2.2% last year, and is currently climbing at a 2.4% rate. In the past three months it has risen at a 3.4% pace. It is on the move. This recent run-up in inflation should cause the Fed to refrain from further rate cuts. But it won’t. The idea that Fed policy is data-dependent has gone out the window. The Fed now does whatever it wants to do and, right now, it wants to cut rates. Perhaps next week we will get a better sense of exactly how far it intends to go.

As we see it, monetary policy is already accommodative and is going to become more so. The probability of higher interest rates any time between now and the end of next year is basically 0%.

At the same time fiscal policy has shifted into serious stimulative mode. Government spending is expected to jump 8.0% this year. The deficit will once again exceed $1.0 trillion with a string of similar-sized deficits in store every year for the foreseeable future. Trump and the Republicans want to get re-elected and are willing to boost spending to make that happen. Democrats want to make college education free, cancel student debt, give reparations to descendants of slaves, and adopt Medicare for all. Neither party has any desire to curtail spending.

If that were not enough, as part of his plan to get re-elected, Trump is likely to pull off a trade deal with China (even a lousy deal). If that happens the markets will soar. The fear of a trade-induced global recession will disappear With wildly stimulative monetary and fiscal policy and a possible trade deal tin the works, there is no way the economy is going to slow down in 2020. The stock market will continue to climb. What’s not to like in the short run?

However, exploding budget deficits and a Fed that has little ammo to counter the next downturn may create significant problems down the road. But who cares about that?

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me