November 8, 2013

In the course of a single week the notion that the economy was expanding at a snail’s pace and employers were extremely reluctant to hire new workers has turned upside down. Third quarter GDP growth came in stronger than expected, and employment in October was much larger than anticipated. Suddenly there is a very real possibility that the Fed could reduce its pace of bond purchases in December rather than March. That action is important because it would represent the first time in six years that the Fed has moved towards a less accommodative policy stance.

Third quarter GDP growth was expected to be 2.0%. Fourth quarter growth was also expected to be weak because, in the eyes of many economists, the government shutdown had so shaken confidence that consumers would be reluctant to spend and employers would gear up for an allegedly anemic holiday spending season by hiring fewer workers than normal.

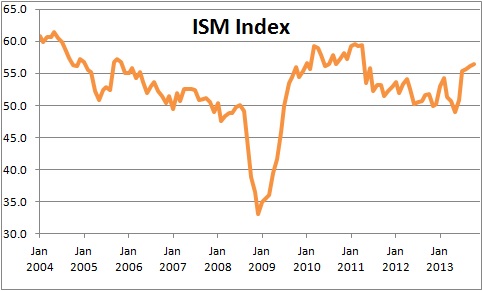

Then it turns out that third quarter GDP growth was 2.8%. It is true that sales growth in the third quarter was 2.0% and inventory accumulation added 0.8% to produce the 2.8% pace of GDP growth. The naysayers argued that the inventory accumulation was unintentional and, therefore, firms would cut back on production in the fourth quarter to get inventories back into closer alignment with sales. But that view makes little sense. First of all, the Institute for Supply Management’s index of activity in the manufacturing sector has risen sharply in recent months and is now close to its highest level thus far in the cycle. The ISM index for the service sector is close to its high for the cycle as well.

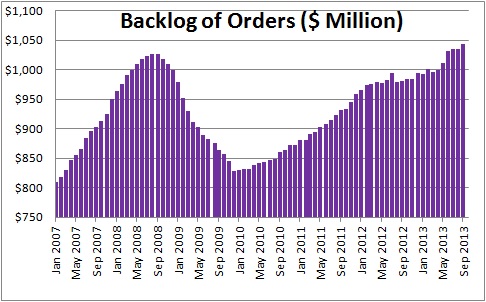

In addition, the backlog of orders continues to grow. If the pile of orders on your desk is getting higher, why would you ever consider cutting the pace of production? That seems absurd.

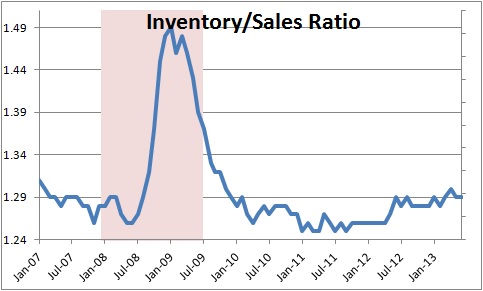

Similarly, the ratio of inventories to sales has been at its current level for more than one year. There is nothing to suggest that it is in any way out of sync with the pace of sales. Furthermore, if business leaders expect sales to pick up in 2014 (which seems to be the general consensus) it probably makes sense to boost inventory levels so they can satisfy an expected increase in demand.

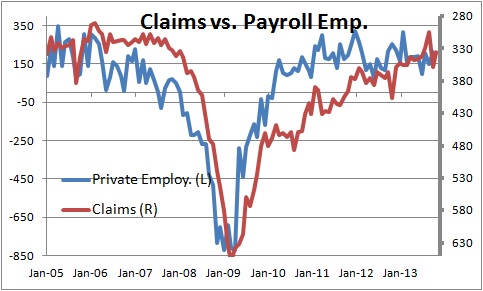

Shortly thereafter we learned that private sector employment rose 212 thousand in October compared to the 120 thousand gain that had been anticipated. In addition, there were upward revisions to prior months that added another 70 thousand jobs. The 3-month average increase in employment is now 190 thousand; a month ago it was 145 thousand. To some the revised jobs data may seem surprisingly strong. But in our view the data are more in line with other labor market indicators such as the initial claims data which are a measure of layoffs. Prior to distortions caused by the government shutdown in early October, claims had been averaging about 315 thousand per week. As shown in the chart below, at that level monthly employment gains seemed like they should be averaging perhaps 180 thousand. The mystery to us was why employment was so anemic. Now, post revision, the employment statistics seem more in line with where they should have been all along.

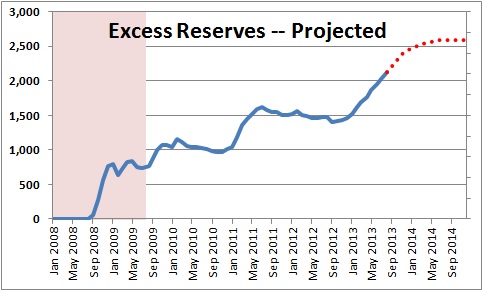

Given the above, how might the Federal Reserve respond? Previously economists thought that the Fed would not slow the pace of its monthly bond purchases until March. Now suddenly the implementation date has been moved forward and becomes a real possibility at the FOMC meeting that will be held in December. This policy shift is important because it would be the Fed’s first step in six years towards a slightly less accommodative policy stance. The Fed needs to make that move soon and, in our opinion, the sooner the better. As it stands the Fed is adding $85 billion of surplus reserves to the banking system every single month. Those reserves are unnecessary and will ultimately have to be eliminated. The longer the Fed delays, the bigger their job will be in the future. That makes no sense. Remember, a reduction in the amount of reserves being purchased each month does not represent a tighter Fed policy stance. It merely represents a slowdown in the pace of easing. Instead of purchasing $85 billion of additional securities each month – and thereby continuously easing – the Fed will trim that amount initially to, say, $50 billion. They will still be easing, but at a somewhat slower pace. The Fed no longer needs to keep its foot on the accelerator. Let the economy coast for a while.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me