July 7, 2023

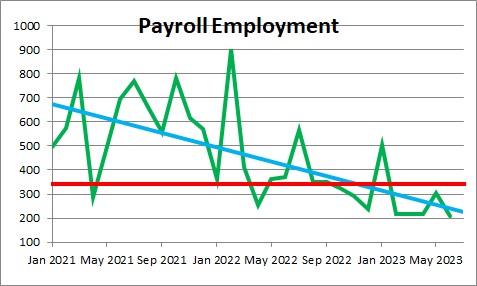

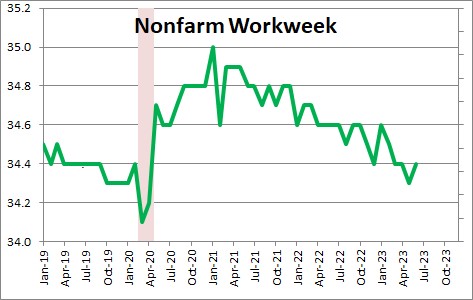

At midyear 2023 the economists who suggest that the economy will slip into recession in the second half of the year must be feeling nervous. The service sector of the economy rebounded in June. The employment report for June was solid with a 209 thousand increase in payroll employment combined with a 0.1 hour increase in the nonfarm workweek. The unemployment rate declined 0.1% to 3.6%. Car sales jumped 4.2%, which suggests that retail sales for June will likely increase by 0.7%. Thus, the second quarter ends on a solid note. Market participants now understand why the Fed is looking for another two 0.25% increases in the funds rate between now and yearend. Like everybody else we believe that a recession is in the cards by early 2024. But we differ from others in that we believe that for that recession to occur the Fed will need to raise the funds rate several more times. The current level of interest rates will not do the trick. A recession is coming, but it is not imminent.

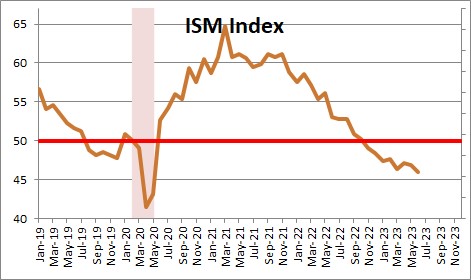

The manufacturing side of the economy has been steadily declining. That sector entered a recession at the beginning of the year and has been continuing to deteriorate since. But it is important to remember that consumer spending accounts for about 70% of GDP. So while the manufacturing sector is important, the driving force behind GDP growth is the consumer.

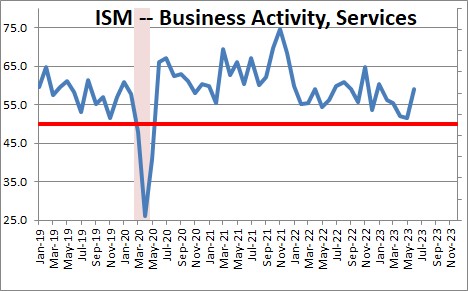

The consumer-driven service side of the economy reached a peak in January and then slowed every month from February to May. Given that trend one might have reasonably concluded that it, too, would soon be contracting. But along came the June data. The business activity index jumped 7.7 points to 59.2, which returns it to its January level. The service sector is not yet on the cusp of a recession.

The employment report revealed that payroll employment rose just 209 thousand in June and some were quick to conclude that the labor market was continuing to soften. But in any given month employers have a choice. They can boost output by hiring more workers or by lengthening the hours worked of those already on the payroll.

In June the nonfarm workweek rose 0.1 hour from 34.3 to 34.4 hours. That seems innocuous. But it represents an increase of 0.29%. If employers had chosen not to lengthen the workweek, they would have needed to hire an additional 452 thousand workers which means that the June increase in payroll employment would have been 661 thousand. If that had been the print for the employment gain in June, the adverse market reaction would have been dramatic. Between the increase in employment and the longer workweek, workers sharply boosted output – think GDP –in the final month of the second quarter.

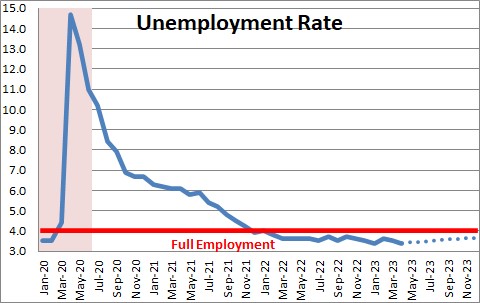

The employment report also indicated that the unemployment rate fell 0.1% in June to 3.6%. The Fed believes that full employment – the level of the unemployment rate at which everybody who wants a job has one — should be 4.0%. In reality the Fed would like the unemployment rate to climb to 4.5% to develop a bit of slack in the labor market which would, presumably, take some of the upward pressure off wages and help bring the inflation rate closer to its 2.0% target. But in June the unemployment rate moved slightly further away from what the Fed would like to see. The labor market got slightly tighter, not looser.

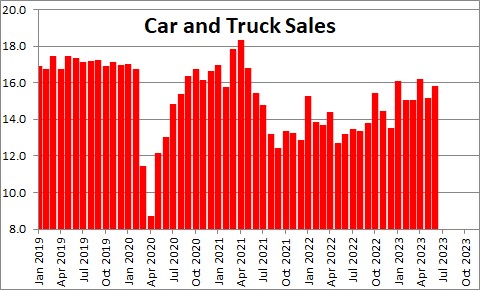

New car sales jumped 4.2% in June to a 15.7 million pace. Car sales have, in fact, been on a steady rise for a year as the supply constraints which curtailed deliveries in 2021 began to abate. If consumers are feeling nervous, they first cut spending on car sales and home sales – the two biggest ticket items in their budget. Car sales are certainly showing no sign of softness.

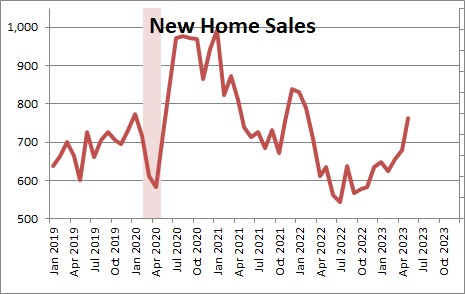

Ditto for new home sales. Existing home sales have been held in check by a dramatic shortage of homes available for realtors to sell because homeowners are reluctant to trade their current 3.0% mortgage rate for a near-7.0% rate today. Unfazed, consumers have turned their attention to the far more abundant supply of new homes. Like car sales, new home sales have been surging. If these two sectors typically provide an early hint of an imminent cutback in consumer spending, they are simply not sending that message today.

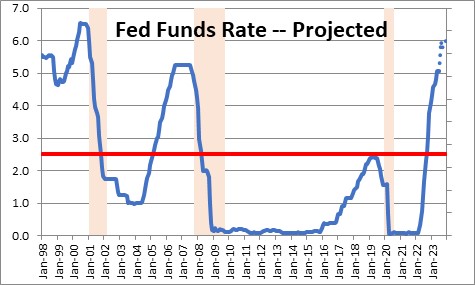

The bottom line is that rates are not yet high enough to bring about the long-awaited recession. The markets have finally accepted that the Fed will raise the funds rate twice more in the summer months bringing the funds rate to 5.75%. But remember that just a month or two ago market participants were expecting at least one Fed rate cut by the end of the year. Now they expect two rate hikes. Is that enough? Probably not.

For what it is worth, we expect the funds rate to reach 6.0% by the end of the year and the core CPI to increase 4.8% in 2023. That would mean that the real funds rate at yearend would be +1.2%. Is that high enough to slow the economy and further reduce inflation? Maybe.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

So does this mean the commodity markets will rebound with the economy not slowing down? Could that create a problem at year end if the fed funds rate is 6%, cpi 4.8% and commodities are taking off? eg Arthur Burns scenario with a more aggressive tighten series to clamp down on the economy?

Good morning Tyson.

I think the economy is slowing down. The question is whether it is slowing down enough to bring down the core rate of inflation. If the economy continues to chug along at a rate faster than what is generally perceived at the moment, I suspect the commodity markets will rebound to some extent. The rest of your questions depend upon the Fed’s response. I get the sense they are serious about bringing down inflation and will do whatever it takes to make that happen. Hence, the idea of an Arthur Burns lack of aggressive action probably will not happen. But who knows? Powell seems to be more of a political animal than any Fed Chair in recent memory. How else to explain the Fed’s lack of action when inflation began to accelerate? The Fed was probably the last group to figure out that the increase in inflation was not just temporary. Good questions. I am not sure any of us (or perhaps even the Fed) can answer them at this point.