May 18, 2017

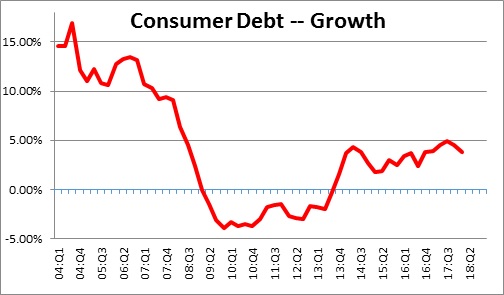

The New York Federal Reserve Bank recently released its quarterly report on consumer finances. On the surface, all is well. Consumer debt expanded at a moderate pace in the first quarter of this year. It rose 3.8% in the past year which is roughly in line with the pace registered in the past several years. There is no hint of the double-digit borrowing binge that occurred prior to the recession.

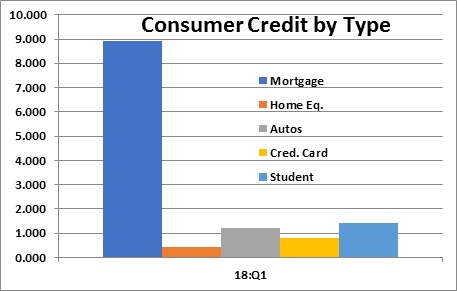

Mortgage lending accounts for more than two-thirds of the total. While overall consumer borrowing also includes auto loans, credit cards, student loans, and home equity lines of credit, they all pale in size relative to mortgages. Given its size, it is not surprising that the growth rate for mortgage lending is almost indistinguishable from the growth pattern for total loans shown above. Over the past year, for example, mortgage loans have risen 3.6% versus 3.8% for the total.

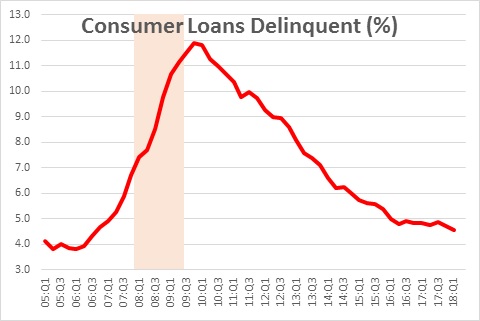

As the economy continues to expand and consumer income rises, seriously delinquent loans as a percent of the total continue to decline and are roughly in line with where they were going into the recession.

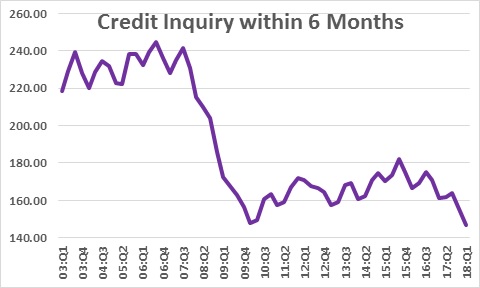

The New York Fed also tracks credit inquiries during the past six months which it uses as a gauge of the demand for credit. This series has been considerably slower than it was prior to the recession. That is no surprise, but its drop in the first quarter of this year seems puzzling. In fact, it is the smallest number of loan inquiries in the history of this series which stretches back to the beginning of 2003. What is going on?

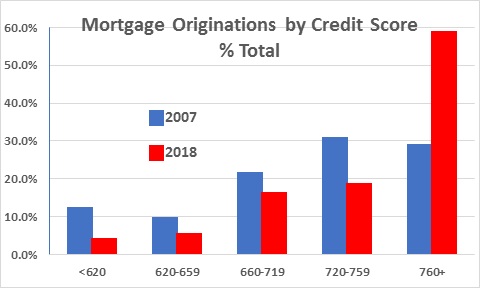

It appears that the subdued pace of growth in credit is primarily attributable to financial institutions demanding far higher credit scores than they did in the past. In late 2007, just prior to the onset of recession, 30% of borrowers had a credit rating of 760 or higher. Today that percentage has doubled to almost 60%. If high credit score borrowers are taking a bigger slice of the pie, all other categories are receiving less. Borrowers with credit scores below 660 almost need not apply. Their chances of attaining a mortgage are small. Prior to the recession borrowers with credit ratings less than 660 received 20% of mortgage originations. Today, that portion has fallen to just 8%. These borrowers with low credit scores are primarily young and without a well-established credit track record.

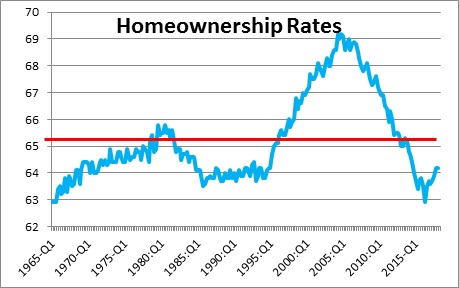

Homeownership rates have touched bottom and, while still below their 50-year average of 65.1, they have begun to recovery from a slide that began in 2004.

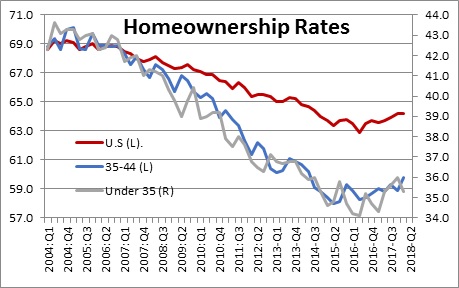

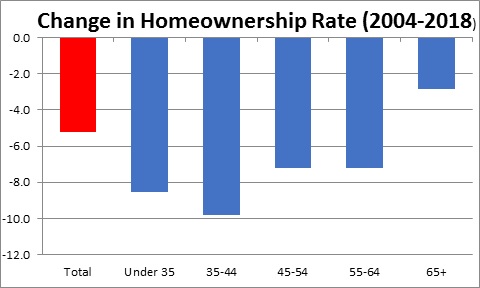

While the overall drop in homeownership is moderate, it is far more pronounced for younger homeowners, specifically the under 35 and 35-44 age brackets.

The same data are shown in the chart below which shows the decline in homeownership rates for every age bracket from their peak in 2004. While the overall drop has been 5.0% (in red), homeownership for the under-35 crowd has fallen 8.3%, and for the 35-44 age bracket the drop has been 9.6%. There can be little doubt that the burden of the tighter lending standards applied in today’s world is falling largely on the young.

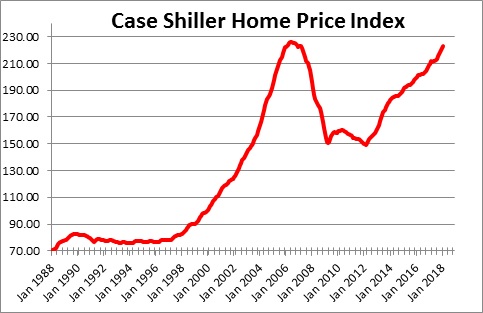

Home prices have fully recovered from the recession. As a result, homeowners now have a record amount of housing wealth, also known as home equity. But tighter lending standards and the reduction in homeownership, particularly for the young, have shifted that housing wealth towards older, higher credit score borrowers.

For example, in 2006 homeowners over age 60 owned 24% of all home equity. By 2017 that percentage had jumped 17 percentage points to 41%. The equity stake of homeowners under the age of 45 fell 10 percentage points from 24% to 14%.

Similarly, in 2006 homeowners with a credit score higher than 780 held 44% of all home equity. By 2007 that percentage had climbed nine points to 53%. This means that homeowners with credit ratings less than 780 saw their equity stake drop nine points to 47%. Because home equity is a crucial form of collateral, young people today do not have access to low cost credit.

Home prices fell sharply during the recession which meant that home equity for many younger borrowers completely disappeared. Many were “upside down” meaning they owned more than their home was worth. They could neither sell nor re-finance. At the same time banks were requiring far higher credit scores than in the past. As a result, younger borrowers have experienced a sharp reduction in their ability to tap sources of low-cost credit.

Are banks being prudent? Or have they become unduly restrictive? Probably some of both. Our hope is that as we go forward lending standards will become somewhat less restrictive.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me