October 26, 2009

There has been considerable concern lately about the recent slide in the value of the dollar which has declined by almost 10% since March. The fear is that the dollar’s slide might turn into a rout, in which case foreigner investors might stop buying Treasury debt at just the time that the budget deficit is exploding. Such an event could lead to a dramatic rise in long-term interest rates, a jump in the inflation rate, and possibly short circuit any incipient recovery. While that sounds like a legitimate fear, how likely is it?

There appear to be a number of reasons for the dollar’s recent behavior.

- It is almost certain that a significant portion of the dollar’s recent drop is attributable to the rapidly escalating size of the U.S. budget deficit. The Treasury recently reported a $1.4 trillion deficit for fiscal year 2009 with trillion dollar deficits likely for at least the next several years.

- The dollar weakness has been exacerbated by an emerging trade war with China that began last month. On September 11 President Obama announced tariffs of as much as 35% on Chinese made tires. Two days later the Chinese announced the imposition of tariffs on U.S. chicken products and auto parts. With employment continuing to decline in the United States other industries such as furniture, fruit and vegetable growers, and flower growers are all seeking import protection. The currency markets fear that protectionist trade sentiments will escalate in the months ahead.

- The markets are also disquieted by a lack of U.S. action to support the dollar. While President Obama has voiced public support for the dollar, thus far it has been all words and no action. The foreign exchange markets fear, rightly or wrongly, that the U.S. is encouraging a weaker dollar as a way to strengthen the domestic economy.

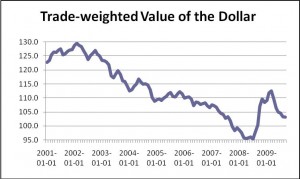

Thus, the dollar’s recent decline seems understandable. But to be fair, the dollar (as shown in the chart below) has been falling steadily since January 2002. In a six-year period it has lost 25% of its value. As the credit crisis evolved and the global economy went into a tailspin late last year a flight to quality temporarily reversed its direction, but it has since resumed its decline. Thus, the dollar’s recent slide is part of a much bigger picture that began long before President Obama took office. During that period of time nothing too bad has happened — interest rates and the inflation rate remain low, and foreigners still buy Treasury debt.

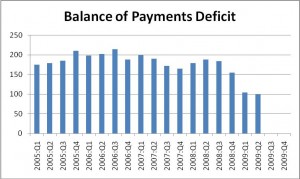

So is a decline in the dollar a bad thing? Not necessarily. As the dollar falls, U.S. goods are cheaper for foreigners, which causes exports to rise. At the same time foreign goods are more expensive for U.S. residents, which causes imports to decline. Both pieces tend to narrow our trade deficit. The balance of payment deficit (shown in the chart below) is the broadest measure of our trade position. After having reached a peak of $215 billion in the third quarter of 2006, the payments gap has been sliced more than in half to $99 billion in the second quarter – despite the sharp jump in the Treasury budget deficit.

Going forward the deficit is likely to shrink further. Typically, the U.S. leads the way out of a global economic slump. As that occurs the trade gap widens — imports rise sharply as the U.S economy gains strength, while exports lag. But this time around growth in Europe, Asia, and the Americas appears to be picking up sooner and with more vigor than in the U.S. because the U.S. consumer is strapped by a particularly heavy debt burden and is having considerable difficulty in obtaining credit. This means that exports should rise faster than imports, and the trade gap will continue to narrow in the months and quarters ahead.

The dollar’s decline thus far has been relatively uneventful primarily because the private sector deficit has shrunk even more rapidly than the Federal government deficit has risen, which has chopped the U.S.’s need for foreign capital in half. Thus, a further gradual decline in the dollar would probably not be a bad thing; a precipitous slide would be an entirely different story.

Follow Me