October 11, 2010

Upon returning from a two-week holiday, during which I intentionally stayed away from looking at the markets and the economy, I find that everybody is suddenly talking about further Fed easing. I feared the worst. I expected to see economic statistics that had somehow fallen out of bed. But, upon review, that does not appear to be the case.

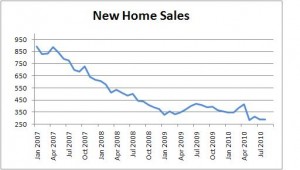

The Fed ease talk presumably began in response to further weak news from the housing sector and from consumer confidence. But the weakness in those two series, in my opinion, is not overly dramatic. Look at new home sales, for example. Yes, it is weak, and home prices continue to decline as foreclosures force prices lower. But consumer income continues to climb, consumers continue to pay down debt, 30-year mortgage rates of 4.3% are at near record-low levels, and lower home prices increase affordability. While there are no signs of a rebound in housing, it is hard to see the housing sector weakening further.

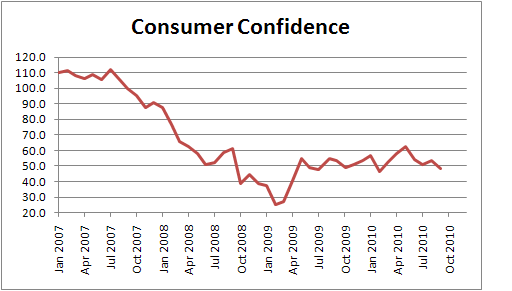

The Conference Board series on consumer confidence declined in September, but it has been bouncing around since the spring of 2009. While the consumer does not feel great — in large part because of the lack of job creation — there is nothing in this series that suggests it has softened.

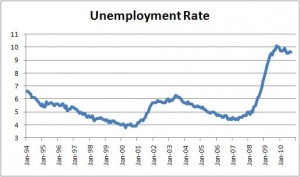

The coupe de grace was the employment report for October which showed the unemployment rate remaining at a lofty 9.6% level. It is unacceptably high and certainly frustrating to policymakers. But it is important to note that the labor force has been rising the past couple of months. This is a very normal development as the economy improves, and is generally regarded as a positive sign. In August the labor force rose by 550 thousand. Jobs did keep pace, so the unemployment rate climbed from 9.5% to 9.6%. In September the labor force rose another 48 thousand. The economy created enough jobs in that month to keep the unemployment rate steady at 9.6%. But the very fact that some so-called “discouraged workers” are beginning to look for employment after having been out of the labor market for so long is a sign of confidence on their part that they might actually be able to find a job. Also, economists know that the unemployment rate is a lagging indicator of the economy. It tells us where we have been, not where we are going. While it is hard for a policymaker to ignore, the fact of the matter is it tells us nothing about where the economy is headed – which is the important variable. If in the months ahead economic activity accelerates, the unemployment rate will eventually resume its decline.

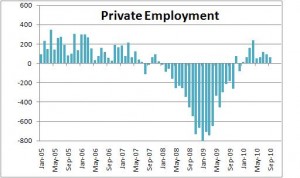

Payroll employment fell by 95 thousand in September. However, 77 thousand of those people were Census workers that have been distorting the data on both the upside and downside for most of this year. In addition, local government employment fell by 76 thousand. Think teachers. Given severe budget constraints some municipalities have hired fewer teachers than normal this year while others have actually laid off teachers – hence the decline. But September – the beginning of the school year — is when those layoffs occur. Thus, it is unlikely that the large September drop in local government employment is a precursor of further big declines in local government employment in the months ahead. If we exclude the government sector and focus instead on private sector employment, we find that employment actually rose 64 thousand in September, and it has risen on average 96 thousand per month since the beginning of the year. While that is still smaller than desired, the fact of the matter is that employment continues to climb albeit slowly.

The nonfarm workweek did not rise further in September. It was unchanged at 33.5 hours. But it has been climbing steadily since late last year. Thus, it is clear that firms need to produce additional output, but they have chosen to do it by working existing employees longer hours rather than hiring additional workers. There continues to be considerable uncertainty about tax rates and the cost of health insurance going forward which makes firms unwilling to commit to hiring additional workers. Who can blame them? Perhaps the midterm election will remove some of that uncertainty.

One other point should be noted. We will get our first look at third quarter GDP on October 29. Most economists are honing in on a gain of about 2.0%, which would be virtually the same as the 1.7% pace reported for the second quarter. Most economists do their GDP estimates from the demand side. That is, they add up the available data on consumption, capital spending, and trade. Looked at in that manner a 2.0% growth rate for the third quarter seems reasonable. But for that initial estimate the Commerce Department has three months of data for consumption spending, and two months worth of data for most of the other GDP components. Thus, that early reading is relatively incomplete and, as we have seen on numerous occasions in the past, it can be subject to large revisions.

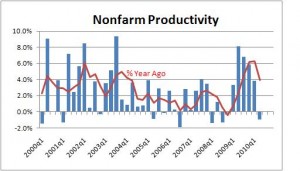

As a check many economists calculate an alternative GDP estimate that is done by looking at the production side using the employment and hours worked data from the employment report. If we know how many people were working and how long they worked, we should have some idea of how many goods they produced – which is what GDP is attempting to measure. Those data indicate that production increased 1.9% in the third quarter. But what if those workers are more efficient and produce more goods? As shown below, productivity has been rising at a very rapid rate of about 4.0% for the past year. However, in the second quarter productivity declined 0.9%. But given strong investment in technology and business equipment during the past year, there is no reason to believe that the trend rate has suddenly turned negative. That makes no sense. But what number should we assume for the third quarter following the surprising decline in Q2? The chart below indicates that almost every time productivity has declined in a single quarter (the blue bars) it has increased in the subsequent quarter. So my bet would be that productivity actually increased somewhat in the third quarter. If it climbs by 1.0%, then third quarter GDP growth would be 1.9% (the increase in production) plus 1.0% (the increase in productivity) or 2.9%. The market is not expecting that. It is looking for growth of about 2.0%. If that guesstimate is correct, there is clearly no need for further Fed easing. Stay tuned. We will get our first look at third quarter GDP on Friday, October 29. The next FOMC meeting will be held on November 2-3. And, if that is not enough, Election Day is November 2. There is a lot going on over the course of the next three weeks.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, SC

Follow Me