December 21, 2018

The Fed raised rates this week which puts the funds rate in a range from 2.25-2.5%. The move was largely expected. The Fed also anticipates two one-quarter point hikes in 2019 which would leave the funds rate at 3.0% by the end of next year. The Fed said it was becoming more “data dependent”, but its official statement and Fed Chair Powell’s comments at the press conference gave short shrift to clear signs of slower growth overseas, a steady drop-off in the pace of home sales, a slightly reduced rate of inflation, and the stock market’s three-month swoon. So why did the Fed raise rates?

We do not believe the Fed was asserting its independence and sending a strong message to President Trump that it would not be intimidated. The Fed does not engage in political gamesmanship.

There is a simpler explanation for its action. The Fed believes that potential GDP growth is 1.9%. The economy is at full employment. It anticipates 3.0% GDP growth this year and 2.3% growth in 2019. Because growth in those two years will exceed the speed limit, the Fed wants to raise the funds rate to a neutral level which it now believes is 2.75%.

Clearly, the markets do not share that outlook. They are worried about Fed policy becoming “too tight”. We do not quibble with the Fed’s estimate of “potential GDP growth” which this week they lowered from 3.0% to 2.75%. But we do take issue with the Fed’s apparent dismissal of recent economic data.

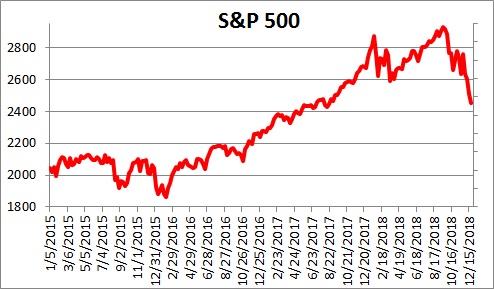

The S&P has now fallen 16.5% from its peak and is approaching a “bear market” which is generally regarded as a decline of 20%. That should give the Fed ample reason to take a breather.

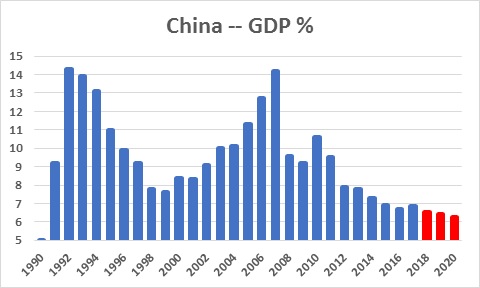

The IMF recently lowered its estimate of GDP growth for China for 2018 to 6.5%. For China that is the worst performance since 1990. The IMF expects even slower growth in 2019 and 2020. A slowdown of that magnitude in the world’s second largest economy will have ramifications around the globe – including the U.S. That should give the Fed ample reason to take a breather.

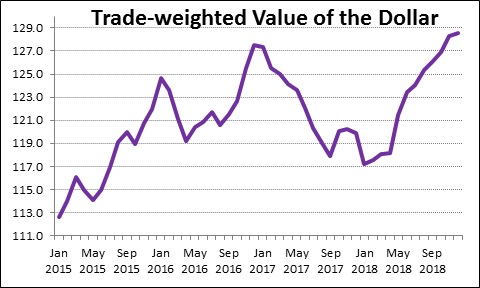

Much of the weakness outside our borders is the result of a stronger dollar which has risen 10% since January. The dollar’s ascent was triggered by Trump’s tariffs on all countries. Other countries retaliated. A trade war was underway. Foreign investors concluded that the U.S. was in a far better position to withstand a trade war than other countries, so money poured into U.S. stock and bond markets in the spring and summer thereby boosting the value of the dollar. But that crushes growth in emerging economies which need raw materials to feed their manufacturing sector. Those raw materials are all traded in dollars. Hence, an increase in the dollar increases the cost of materials for emerging economies, impedes their ability to compete in the global marketplace, and leads to a weaker economy. A Fed rate hike serves to increase further the value of the dollar and accentuate that economic weakness. That should give the Fed ample reason to take a breather.

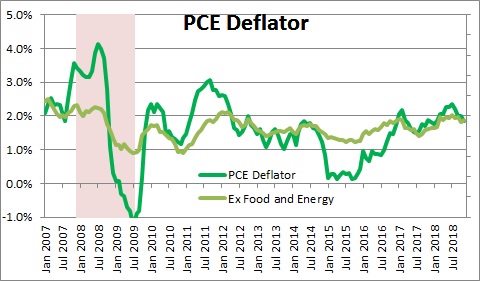

Inflation has been coming in lower than expected. The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the personal consumption expenditures deflator excluding the volatile food and energy components, has risen 1.9% in the past year. But in the past six months that has slowed to 1.5%, and in the past three months to 1.7%. It is certainly not accelerating! That should give the Fed ample reason to take a breather.

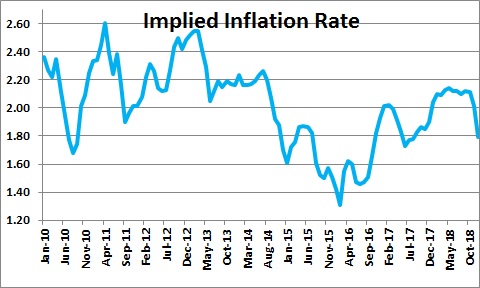

The market’s expected rate of inflation for the next decade can be estimated as the difference between the yield on the Treasury’s 10-year note and its inflation-adjusted equivalent. It had been at 2.1% for almost a year but recently slipped to 1.8%. That should give the Fed ample reason to take a breather.

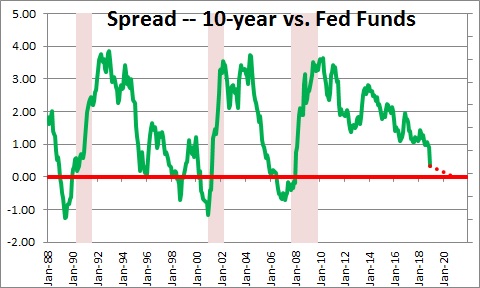

In the wake of the Fed’s rate decision short rates rose while long rates declined. As a result, the yield curve, which is the difference between long-term interest rates and short rates, flattened by 0.6% from -1.0% to 0.4%. The yield curve has not yet inverted – which happens when short rates become higher than long rates – but it is a lot closer now than it was on Wednesday morning. An inverted curve is a warning signal that a recession is likely within a year or so. That should give the Fed ample reason to take a breather.

We disagree with the Fed’s decision to raise rates at the meeting this past week. Nevertheless, it is hard to imagine a funds rate of 2.25-2.5% or even the 3.0% rate expected by the end of next year, as being high enough to push the economy over the edge into recession. Having said that, the relentless stock market slide combined with breathtaking volatility is bound to shake consumer and business confidence at some point. While a recession is not in the cards, GDP growth could slip a notch or two. We currently project 2.8% GDP growth in 2019. We are going to wait and see what happens in the early part of next year, but for now the risk seems to be on the downside.

The Fed did not help itself or the economy on Wednesday.

Stephen Slifer

NumberNomics

Charleston, S.C.

Follow Me